One of the first questions I typically receive when I mention to farms that I am a labor management consultant is, “Am I paying my employees enough?” It is no secret that starting rates, pay structures and state-wide minimum wage is on every business owner’s mind.

Agriculture is not necessarily unique from any other family business in the U.S., where owners may or may not be able to take a paycheck home during difficult months and low economic seasons.

However, we do differ from other industries in the way we are regulated from a labor perspective. For those who scoff at that statement, some examples of this include farms being ignored by OSHA’s labor safety standards until 2009, and very few farms fall into the audit parameters of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) due to our creative abilities to skirt the gray areas in regulations in agriculture.

Nevertheless, as we feel the season of change in the direction of unification to other industries hanging in the air, there are important areas to consider in the topic of pay structures and regulation compliance.

Do your wages meet the cost of living needs for your employees?

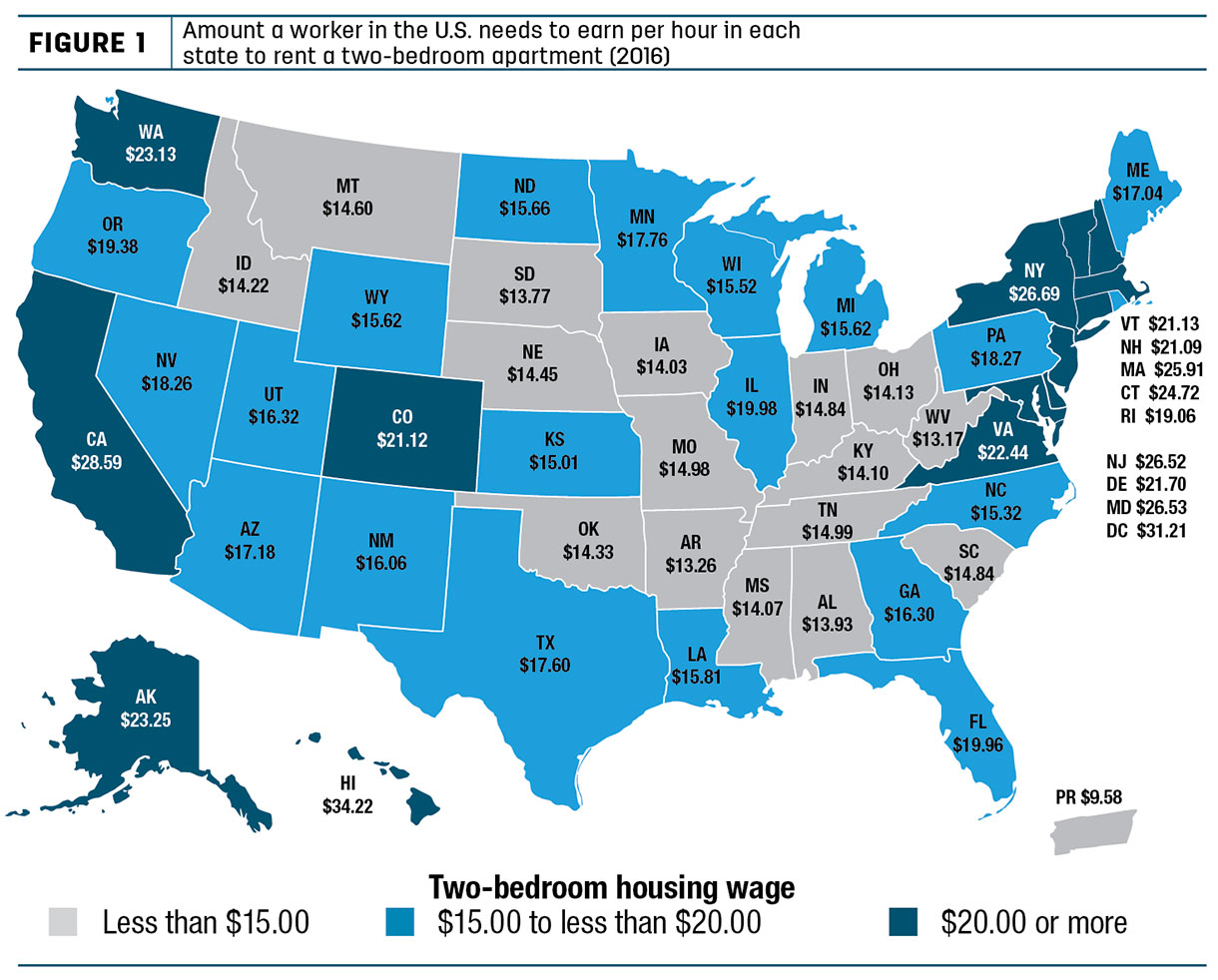

The first consideration for any compensation package is the cost of living in the position location. Any employer should be aware of the general cost of living for his or her place of business. The National Low Income Housing Coalition recently came out with a map using research from the Pew Research Center to depict the amount a worker in the U.S. needs to earn per hour in each state to rent a two-bedroom apartment.

Major dairy states such as California, Wisconsin and New York hit $26.65, $15.52 and $25.67 per hour, respectively. Obviously, major cities skew the data, but the information helps provide perspective as states like New York consider increasing the state-wide minimum wage to $15 per hour.

Click here or on the image above to view it at full size in a new window.

Depending on where your farm is located, your wages should incorporate qualities such as distance from town (travel), taxes, rent or housing rates in the area, utilities, etc. There are multiple tools available through state and federal census data, but another method of determining cost of living is to consider your personal monthly expenses.

Take into consideration family size, spouse income, utilities and major capital purchases. This expectation should not be too different than what your employees have to pay.

What is the return on your wage investment?

Gross profit margin is determined by the difference between the investment into the product (inputs) and the price received for the product (outputs). To maximize this margin, an ideal transaction would have the lowest input cost and receive the highest price for the output.

For a moment, embrace your inner Wall Street investor, and consider your employment structure. Each employee wage on your farm is an investment (input) that performs tasks of varying skills (outputs). Does every employee on your farm produce outputs that provide an equal or higher return on his wage?

For example, do your milkers only milk, or have they been trained to also identify sick cows, perform cow-side mastitis tests and keep health records for the parlor? Any additional training that you can invest into an employee adds value to his or her position, saving you time and costs in other areas.

Turning an employee who started out as a $10-per-hour employee into a $12-per-hour employee through training can save a $15-per-hour employee time and energy to invest in tasks that require more skill.

What is the value to the benefits you provide?

As a consultant, my favorite response is the farm that says, “My employees get $8 per hour, but free housing with cable and utilities.” There have been many times when the farm should be paying the employees to live in the housing environments provided.

Although employee housing can be a nice idea, the reality is that most dairy farmers are farmers and not real estate property managers, for good reason. Benefits should always be offered; the only variation is the form, and each employee will value every form differently.

Different forms of benefits can include health insurance, paid holidays, housing, vehicles, cell phones or upfront compensation to cover these necessary living expenses. In addition, most forms of benefits can be quantified. For example, a health insurance policy may cost an employer $10,000 a year, which would equal about three additional dollars per hour for the employee in a 60-hour work week.

As individual states increase their minimum wage standards, business owners who depend on hourly structures cringe as they see their labor expense increase exponentially while their employees ask to work less hours to keep their annual income at the levels to remain eligible for government insurance programs.

As agriculture continues to conform to federal standards of how we manage labor, our compensation structures need to be built upon quantitative information versus an arbitrary rate that is comparable to the farm next door. ![]()