As one evaluates margins, the wild fluctuation in summer markets changed the outlook of many a dairyman. Stories of coming drought and the consequential lack of feed grains caused markets to climb substantially in the second quarter of the year. Corn prices rallied 85 cents from spring lows. Soybean meal shot up $150 per ton.

This took place amid one of the best planting seasons in recent history and while crop development carried a condition score that shares very few rival years. With adequate rainfall in the forecast, prices began a retreat from their highs (which were very obedient to the ranges discussed in my April article) back to new lows in corn and substantially more affordable soybean meal.

On the other side of the equation, milk prices were whittled down to levels not seen in six years. Milk production around the globe was continuing to rise, and inventories grew to record levels. The sentiment changed quickly, however, when fresh barrel cheese became sparsely available.

Buyers, both on and off the CME spot dairy trade, paid a premium to find cheese that met specifications. Prices moved higher through June and July. At the time of this writing, cheese prices are more than 50 cents higher than their May lows.

At the same time, inventories of product continue to grow, milk production maintains a steady flow, and international prices hover at levels substantially lower than domestic levels.

On both fronts, rather large moves took place at a time when their departure was frankly unexplainable. Throughout the course of the movements, the price action was often unjustified. The reality of the market is that while the fundamentals surrounding the market had not changed, the people did – lesson one.

Logic did little to explain valuation. However, human mindsets were looking past the existing fundamentals toward future potential outcomes.

Using corn as an example, we seldom see a spring season as good as the one witnessed this year. Corn planting was 64 percent complete by the first week of May. That does not necessarily predict a large crop, but it does remove the concern about late planting and a later pollination window allowing stress to lead to a shortened yield.

With adequate soil moisture, the crop progressed nicely and continued to score well in the eyes of field observers. From the start, corn did not see less than 75 percent of its acreage rated as good or excellent all the way through July. The implication nationally was for a very large crop.

In May, concern did grow as to the size of the Brazilian corn crop. In June, the USDA trimmed production by 3.5 million metric tons (137 million bushels or the U.S. production equivalent of 1.5 bushels to the acre). None of this news together could warrant an 85-cent run in prices.

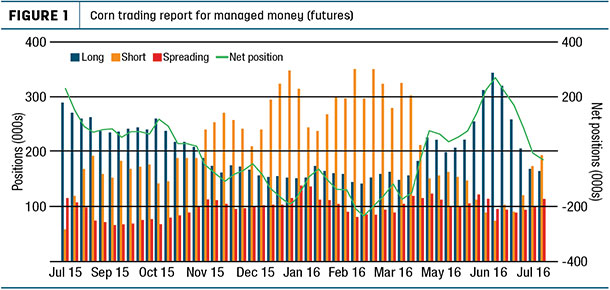

However, speculative money was piling into commodity markets as drought stories consumed the conversation, and cheap world money was shopping for better returns. While the fundamentals of the market hadn’t turned wildly bullish, the people in the market had. A quick look at the position held by “Managed Money” tells that story (see Figure 1).

Finding an explanation for what happened next was even more challenging. Long-range weather forecasts from a myriad of weather “gurus” suggested a warmer but wetter July. One particular expert disagreed (which was much of the driving force in the move higher) and called for a blazing hot and much drier outcome.

Exuberance about an alternate outcome fed on itself even while the vast majority of forecasts remained warm and moist. Eventually, the “bull fever” that gripped the market ran dry. Traders got cold feet. Markets plummeted.

Here is where a word of caution is warranted. (One that comes from a dad with four daughters. I am reminded often that they reserve the right to change their mind at any time. And they do.) The mind of the trading community is a fickly one and can be changed quickly.

After the markets began their fall, the USDA trimmed its Brazilian production by another 7.5 million metric tons (295 million bushels or 7.5 bushels per acre). While a much smaller cut was used as justification for market movement at the start of the price rally, the larger cut was dismissed. Markets continued to erode. Again, the human mindset had changed. Fundamentals were given little credence.

All of this is not to say that the guideposts built on market knowledge should be ignored. While guiding fundamental information can be dismissed in the short term, it will always rule the long term – lesson two. You may have heard the expression, “High prices are the cure for high prices,” or its low-price parallel, “Low prices are the cure for low prices.”

An arrangement of fundamental information that creates large supply or strong demand features will ultimately cause the logical price outcome, even if ignored for a brief time. Any changes in that information or governing bias will cause a retraction.

The challenge in commodity futures markets is: It can often be difficult to separate current realities from coming possibilities to arrive at an agreement on how prices should behave. The outcome of this is a frustrated attempt to understand or appreciate what is happening.

However, long-term, the frustration is often eased as the coming possibilities are sifted down to become the current reality. In this process, it requires us to be nimble and flexible in how we address price.

Lesson three – ongoing explanations of each move in the market are not always necessary to make sound marketing and risk management decisions. While life is much easier when we have an array of facts to support our decisions, markets don’t always provide us such a luxury.

Building off the conversation about current realities versus coming possibilities, it is imperative that we not overlook the most important reality of all: profitability. Marketing and risk management are not about beating the market but rather about sustaining long-term profitability.

July feed costs were roughly $1.50 lower than where they had peaked in June as they returned to approximately the same levels. With the run in milk prices, Class III base prices rose by $3 to $4 per hundredweight, while Class IV grew by $2 to $3 per hundredweight. Conservatively, this added $3 to $5 per hundredweight back to the bottom line of dairies around the country.

While not every move of any of the involved markets could be fully explained, the reality was that opportunity reappeared. Did you capture it?

Given the span of time between when this article was written and when your eyeballs are actually reading this, it is impossible to know what has come in the last several weeks. However, as my eyes gaze at milk price offerings in the coming months, most are within striking distance of their recent highs. Grain prices have retreated significantly.

Weather looks benign. Milk production continues to be abundant. Inventories of feed and dairy products are comfortable. Perhaps a new piece of information has come along to support much better income over feed margins. Perhaps not.

As market participants reserve the right to change their minds, these opportunities could change quickly. Summer markets have served as great reminders and wonderful instructors. The lessons learned are not new but still prudent. Given what we have seen as we observe the past and what we see as we look forward into the future, the question remains: “How have you responded?” ![]()

DISCLAIMER: The information contained herein is the opinion of the writer or was obtained from sources cited herein. It should be noted that the impact on market prices due to seasonal or market cycles and current news events may be reflected in market prices. Trading in futures products entails risks of loss which must be understood prior to trading and may not be appropriate for all investors.

-

Mike North

- President

- Commodity Risk Management Group

- Email Mike North