The EPA on Dec. 29 issued its pollution controls aimed to restore the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. Calling it a “pollution diet,” EPA established its final total maximum daily load (TMDL). This action identifies the necessary reductions of nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment from the watershed to clean the Bay and the region’s streams, creeks and rivers by 2025, with 60 percent to be completed by 2017. The agency said that continued poor water quality, despite 25 years of restoration efforts and federal consent decrees, dating from the late 1990s, prompted the TMDLs.

President Obama’s May 12, 2009, executive order regarding this “national treasure” intensified and accelerated EPA’s action.

Shawn Garvin, EPA’s Region 3 Administrator, when announcing the TMDLs in a press conference call, said it was a “historic moment,” and added that it’s the most comprehensive water quality roadmap EPA has ever done.

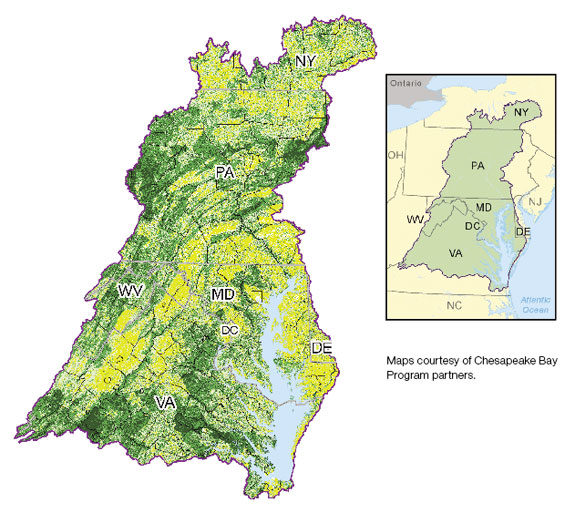

The Bay TMDL is the largest and most complex, and consists of 92 separate TMDLs. The watershed encompasses 64,000 square miles. It includes the District of Columbia and large sections of Delaware, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia and West Virginia.

The TMDL limits nitrogen to 185.9 million pounds, phosphorus to 12.5 million pounds, and sediment to 6.45 billion pounds per year – a 25 percent reduction in nitrogen, 24 percent reduction in phosphorus and 20 percent reduction in sediment.

The TMDL standards include rigorous accountability and enforcement measures. EPA has said it could withhold permitting and federal funding and impose mandatory programs.

In evaluating each Watershed Implementation Plan (WIP) required of each state, EPA indicated actions it would take if load allocations were not met in the two-year milestones. These were delineated by sector – agriculture, urban stormwater and wastewater.

In agriculture, EPA state actions focused on enhanced or ongoing oversight of the animal feeding operations and permit reviews. Enhancing compliance with states’ regulations, and specific actions such as banning winter manure spreading and barnyard runoff control, will be assessed and adjusted.

Impact on dairy producers

Of the six watershed states, two have dairy herds with more than 500,000 head. The USDA estimates New York’s milk cows at 611,000 head in 2010, and Pennsylvania at 541,000 head.

Only the south-central portion of New York is in the Bay watershed. Commenting on New York’s WIP, EPA said New York built its WIP on the strength of its Agricultural Environmental Management (AEM) and concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFO) programs.

Further, AEM captures 95 percent of dairies in the watershed, and farms must participate in AEM to get Farm Bill funding. CAFO permits are required at dairies with as few as 200 animal units, and every field covered by a nutrient management plan is tested for phosphorus.

Also, the state had realistic best management practice (BMP) rates and may consider regulating pasture fencing, plus it outlined advanced dairy manure-processing technologies.

New York State Acting Agriculture Commissioner Darrel J. Aubertine comments, “Through our existing AEM program, New York has demonstrated to EPA that a voluntary approach to on-farm environmental stewardship works to accomplish watershed goals.

There are still many challenges to meet by 2025, but with the continued support of the AEM program, its educational, technical and financial resources, along with its strong partnerships, we are confident that we can meet the desired goals of the EPA without imposing additional regulations in production agriculture.”

Two-thirds of Pennsylvania – the entire central portion – lies in the Bay’s watershed. By far the largest in the Bay area, the Susquehanna River Basin covers 21,000 square miles.

John Frey, executive director of Pennsylvania’s Center for Dairy Excellence (CDE), says a very large percentage of Pennsylvania dairy farms are located within the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Frey points out that the impact of the TMDL changes will differ according to the extent of the farms’ BMPs already in place.

For example, the manure winter application ban proposal will affect smaller dairies which lack extended storage capacity, and Frey notes that the local state conservation district estimates the cost to build manure storage approaches $1,000 per cow.

The required new manure management plan, expected to be released this spring, will cover nitrogen and phosphorus rates, application setbacks, winter application, pastures, barnyard runoff and storage and stacking criteria.

The concentrated animal operations (CAO) plan addresses all nutrients, plus certified planner development, conservation district approval and public comment and annual inspection requirements.

Recognizing that the dairy industry must deal with the TMDL requirements, Alan Zepp, CDE’s risk management specialist, observes, “Regulators must understand that today’s commodity markets do not allow individual farms to absorb the costs associated with regulation compliance.”

Dairies will be included in the TMDL stormwater runoff regulations. More rigorous requirements are expected for mortality management, vegetative buffers, stream bank fencing and no-till planting. Manure-processing technologies will necessitate new research for smaller-scale viability.

In addition, Frey notes discussions regarding capping expansion in the Bay watershed for existing CAFOs, even if the farm has access to an adequate land base. He says, “That could forever cap the ability to accommodate family members to join a growing business.”

Lamonte Garber, agriculture program manager for the Pennsylvania office of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF), said an important point of Pennsylvania’s WIP relating to agriculture is compliance.

“There have been good environmental standards on the books since the ’70s. The WIP focus is getting all farms into baseline conservation with existing regulations to achieve the agriculture reductions,” he says.

Garber estimates that half of Pennsylvania farmers lack basic compliance.

Garber pointed out that without strong federal oversight, states do not take some of the more difficult funding and policy steps. “Even in good budget years, agriculture was woefully underfunded.”

One example is Pennsylvania’s REAP, its resource enhancement and protection tax credit program. Garber recalls that in 2007, the CBF, the Pennsylvania Farm Bureau (PFB) and others worked together, and requested funding of $30 million per year.

“At that time, the goal of the TMDL was roughly the same,” he recalls. However, only $10 million per year was approved – a fraction of the film industry tax credit. Farmers oversubscribed REAP within days. And, in this difficult economy, the program was halved to $5 million.

Garber said the CBF sees agriculture as a much-preferred land use to development. “Good farm operations contribute less pollution per acre than development,” he analyzes. To reduce agriculture’s impact on the Bay, committing funds to strengthen agriculture will result in pollution reductions.

Acknowledging that some requirements, such as barnyard improvement, will be a hardship for some dairy farms, Garber noted others, including precision feeding, stream bank fencing, no-till production and cover crops, make good economic sense.

Citing the loss of 14 percent of dairy farms between 2006 and 2009, Garber concludes that the industry’s fundamental problem of low milk prices and high feed costs, not clean water programs, should be fixed.

He adds, “Some groups are focusing on overturning the TMDL. It’s not the threat to Pennsylvania agriculture that has been claimed.

“The next best opportunity is to work together for strong funding programs. CBF is working hard to secure EQIP and other conservation programs,” Garber stressed.

EPA figures challenged

A continuing concern of numerous farmers throughout the WIP process, including dairymen, was that BMPs that had not been cost-shared were not counted when EPA developed the TMDL allocations.

The Agriculture Nutrient Policy Council’s Dec. 9, 2010, report questioned EPA’s data and model. Prepared by LimnoTech, the report compares EPA’s TMDLs with USDA’s draft report, “Assessment of the Effects of Conservation Practices on Cultivated Cropland in the Chesapeake Bay Region.”

The report points to inconsistencies in the data and modeling. For example, the report says that USDA estimates conventional tillage at 7 percent, while EPA estimates 50 percent. USDA shows 88 percent of cropped acreage to be under conservation tillage of mulch or no-till; EPA estimates conservation tillage at 50 percent.

USDA reports sediment loads to the Bay at 6,855 thousand tons, 14 percent from agriculture. EPA indicates sediment as 3,900 thousand tons, 65 percent from agriculture.

Farm groups sue EPA

On Jan. 10, 2011, the American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF) filed a lawsuit to halt EPA’s TMDL plan. The Pennsylvania Farm Bureau (PFB) joined the suit the same day.

The objections include the charge that EPA unlawfully “micromanages,” rather than allowing the states to decide actions under the Clean Water Act; EPA relied on inaccurate assumptions and a flawed model; and EPA violated the Administrative Procedures Act by failing to allow meaningful participation on the new rules.

The Chesapeake Bay Foundation immediately responded, charging that the suit is not pro-farming but anti-clean water. CFB president Will Baker said, “Litigation will be long and costly for all involved and will likely do nothing but frustrate progress – perhaps the Farm Bureau’s real intent, in spite of rhetoric saying they support clean water.”

The director of government relations for the National Milk Producers Federation, David Hickey, reports, “NMPF believes the lawsuit is the logical outcome given the major questions surrounding inadequate data and overreaching federal authority by the FDA.

We concur with the key tenets of the complaint, as the Chesapeake Bay Watershed TMDL could result in irreparable harm to the region’s dairy producers. It is important to continue the vital cleanup of the Bay; however, the TMDL puts an unfair burden on the agriculture community.”

The next step

The Chesapeake Bay Watershed fiscal year 2011 action plan includes $490,550,424 among the 10-agency “federal family” for the Bay. Of that, $153,578,000 is allocated for agriculture through USDA, the bulk of it ($149,740,000) through NRCS programs.

Of course, the individual states have funding programs as well. New technology and nutrient trading credits are expected to play a larger role in Pennsylvania.

Restoring America’s impaired waterways is a long-standing, ongoing priority for EPA. In addition to efforts to restore the Chesapeake Bay, there are concerted efforts focusing on lakes, rivers, bays and other waterways across the entire country.

In introducing the Chesapeake Executive Order Strategy on May 13, 2010, Nancy Sutley, chair of the White House Council on Environmental Quality, said this unprecedented effort by the federal government reflects the cornerstone principle of the administration’s overall approach to environmental improvement – science-based, collaborative and community-driven conservation.

She added, “The solutions that we employ and develop here in the Chesapeake will inform our national environmental initiatives and can serve as a model for restoring important aquatic ecosystems all around the United States.” PD

Dorthy Noble is a freelance writer based out of Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania.

IMAGE The EPA has established its final total maximum daily load (TMDL) for the Chesapeake Bay watershed (pictured top right), noting it is the most comprehensive water quality roadmap the agency has ever done. Maps courtesy of Chesapeake Bay Program partners.