There was a time long, long ago, before electric milking machines and refrigeration, before modern technology and the slow disappearance of the farmer, that every dairy cow in the world spent most of its productive life grazing on a pasture.

Cows made milk from the forages that they grazed, and the feeding of grain was almost unheard of. This was when farms still numbered in the many hundreds of thousands, and average herd sizes were but a few cows and the “big dairies” had a couple dozen cows.

Every town and township had many dairies, and the rural way of life was more the norm than the exception.

Even though the dairy cow is a ruminant that requires a forage-based diet, better science, higher land values and the relentless pursuit of efficiencies have directed the industry away from pasture.

After all, the two most disadvantageous realities about forages and pastures are their seasonal limitations and their variability in nutrition and quality. Pound for pound, forages supply neither the energy levels nor the energy densities needed for cows producing 25,000 pounds of milk per year.

There is a renewed interest in pasture-based dairy farming in the U.S., and the point of this article is not to criticize or present pasturing systems in a negative light.

However, dairy farmers who pasture their herds so cows derive the majority of their nutrition while grazing must understand that those herds will not be producing 20,000-pound herd averages.

Even on excellently managed pastures of the best quality grasses, cows are hard-pressed to consume adequate amounts of dry matter to meet energy requirements for even 15,000-pound averages in Holstein herds.

Cows grazing on pasture have increased energy requirements due to the increased walking activity, which makes excellent pasture management even that much more important in grazing systems.

One study showed that cows on pasture consumed about 20 percent less dry matter compared to cows consuming TMR diets. Another study determined that lactating cows may only graze for five to six hours per day.

Even though this makes for attractively less input costs for a grazing dairy, milk production is also greatly reduced, as well.

An obvious solution to low dry matter intakes is to supplement a grazing herd with grain mixes. This is generally accepted as a means to improve milk production due to the increased energy density available through the supplements and the fact that total dry matter intakes also increase. The challenge for the dairy farmer is to find that most economical balance of how much grain to supplement.

It’s well-known that excessive levels of grain supplementation in dairy cow diets will lead to unstable pH levels in the rumen. The pH level, which is a measure of acidity, must remain in a tight range of 6.0 to 6.2 for optimal cellulytic (plant fiber) fermentation.

Dropping below 6.0 creates a hostile environment for rumen microbes, and a rumen with a pH of 5.8 is considered to be subclinically acidotic. A rumen pH of less than 5.0 is considered to be very dangerous for the cow.

A recent study conducted at West Virginia University analyzed the changes in pH levels of pastured cows being fed varying levels of grain concentrates.

The study consisted of supplementing a group of grazing dairy cows with one of three different treatments of grain supplementation and closely monitoring pH during the course of the day, with the ultimate objective of evaluating variations in milk production. The grain treatments were 4 kg (8.8 lbs), 8 kg (17.6 lbs) and 12 kg (26.4 lbs) per cow per day.

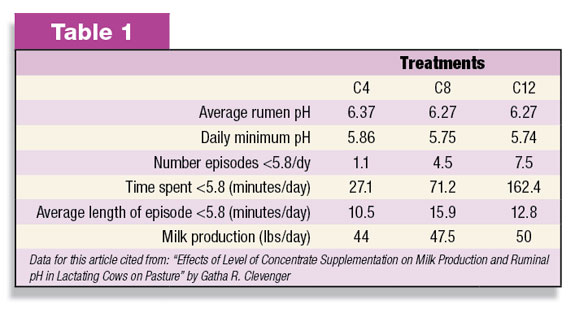

The outcome of the study determined that as the grain was doubled and tripled in the diet, milk production only increased from 44 lbs of milk for the low-grain diet (C4) to 47.5 lbs of milk for the mid-grain diet (C8) to 50 lbs of milk for the high-grain diet (C12).

There was a significant increase in the monetary cost for these diets with an increase of more than 17 lbs of grain – far too great to justify the minimal increase of 6 lbs of milk production.

As grain levels increased in the diet, rumen pH levels dropped to 5.8 or lower for each of the three treatments. ( See Table 1 ).

Even though the average pH for the day was over 6, cows in the C12 treatment averaged 7.5 episodes of pH less than 5.8, with a total time of 162 minutes (2.7 hours) during the course of a day.

The cows eating the least amount of grain experienced only 1.1 episodes with pH less than 5.8 that lasted an average of 27 minutes.

The study very conclusively demonstrated feeding more than 9 or 10 lbs of grain supplements to dairy cows on pasture did much more harm than good. The more often the rumen pH dipped below 5.8 and the longer it remained that way was very detrimental to fiber digestion and any expected increase in milk production.

Whether a dairy farm is a pasture-based system or a confined system, dairy farmers are generally encouraged to increase dry matter intakes in their herds because, most of the time, milk production will increase proportionately.

On a pasture-based dairy system, as the cows consume more grain, their capacity to increase dry matter intakes increases, as well – but only to a point. Due to the disruption of rumen pH, feeding grain beyond 10 lbs appears to have no added benefit for milk production.

Slug-feeding may also be an issue here, indicating that TMR diets can tolerate much higher levels of concentrates before acidosis becomes an issue. And the increased levels of subclinical acidosis may also contribute to laminitis.

Based on this West Virginia study, it appears that not only do pasture-based systems not allow for high levels of milk production but are also limited as to how much grain supplementation is beneficial.

For every pasture-based dairy, a significant effort must be made in determining the nutritional value of the pastures before adding grain to the diet.

Due to the significant regional variabilities of climate and grasses, when attempting to increase milk production, every pasture-based dairy farm must develop its own appropriate grazing model. PD

References omitted due to space but are available upon request to editor@progressivedairy.com .

-

John Hibma

- Nutritionist

- Email John Hibma