There’s an old saying in horse racing circles. “No hoof, no horse.” It refers to the simple truth that even the fastest, strongest and most well-bred colt can’t run if he’s not sound. Dairy cows aren’t runners or even particularly athletic, but the same phrase could easily be modified to “No foot, no cow” to describe the impact lameness has on dairy cattle performance. Although that wouldn’t be completely accurate because lameness can hobble bulls too, adding them to the list of “physically unable to perform” animals.

Lameness is one of those nagging problems that’s usually present in all herds to a certain degree and is a constant barrier to reaching and sustaining peak performance. University research puts the clinical incidence of lameness in dairy cows at 35 percent, meaning at any given time, in any given herd, three out of every 10 cows can be clinically diagnosed as lame.

Ninety percent of all dairy lameness involves the foot, with foot rot accounting for a large percentage of cases. And foot rot is known to cause substantial economic losses in dairy herds. But prevention strategies, including vaccination and environmental or facilities management, can drastically reduce the prevalence of foot rot and monetary losses associated with the disease.

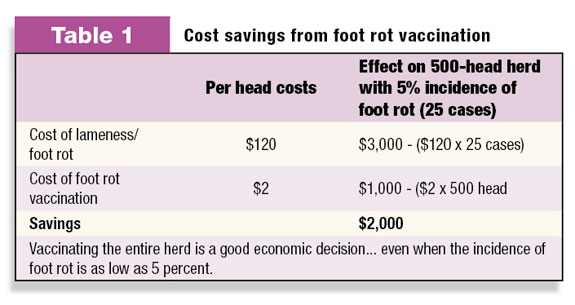

In fact, data from recent field trials shows that vaccinating herds for foot rot will nearly always provide a positive return on investment, even if overall incidence within a herd is as low as 5 percent.

Before evaluating the economics of preventing foot rot, it’s important to understand how the disease causes financial losses on the farm and how it’s contracted in the first place.

Foot rot costs and causes

From an economic standpoint, the costs of foot rot are far greater than treatment alone.

Foot rot leads to reduced milk yields, lower reproduction performance, increased involuntary cull rates, discarded milk and labor tied up in managing afflicted cattle.

Estimates vary on the exact cost per incidence, but they’re all high. Cornell University researchers estimated that overall lameness (of which foot rot is considered a major factor) costs dairy producers $346 per episode. This includes additional days open, involuntary culling and an average of 750 pounds of lost milk production.

One of the most recent studies specifically on foot rot conducted by the University of Nebraska estimated the cost at $120 for each animal.

The most common cause of foot rot is the bacterium Fusobacterium necrophorum, an organism commonly found in the digestive tract of cattle. This same bug has also been identified as causing liver abscesses. Because the bacteria that causes foot rot is a natural inhabitant of the rumen, all cattle are at risk of contracting the disease.

Foot rot usually starts from an injury to the area between the toes. The bacteria that passes out of the body with waste enters the foot through a cut, abrasion or puncture in the interdigital space. It can also occur when bacteria escape the rumen and circulate internally.

One of the biggest misconceptions about foot rot is that cattle must have an open cut or wound on the foot in order for the infection to enter their system. The fact is, simple bruising provides an opportunity for the bacteria to proliferate in the area and cause infection.

The first clinical signs of foot rot are swelling and lameness in one or more feet. Swelling develops rapidly, causing a separation between the toes and a more severe lameness. The area will ultimately become necrotic and break open, rendering the characteristic foul odor associated with foot rot.

Reduced appetite, reduced milk production and poor weight gain are secondary effects. Although rarely fatal, the condition is contagious, which means it can lead to recurring episodes within a herd.

Housing and environment

Housing and environment almost always play a role in the development of foot rot. The disease frequently occurs after cattle encounter abrasive surfaces, stones, dried mud or foreign objects like nails in pens or pastures. And cows confined to concrete are more predisposed to foot rot.

Many people believe that cattle are only susceptible to foot rot in wet, muddy conditions in late winter and early spring, and it’s true that time of year produces a high incidence of foot rot. But those muddy surfaces dry and harden in warm weather, leaving uneven terrain that can easily promote bruising and abrasions. The risk of dairy cattle contracting foot rot is really present year-round. Cattle are less likely to develop foot rot in environments that are frequently cleaned and not overly populated.

Economics of prevention

Based on the University of Nebraska study that estimates the cost of foot rot to be $120 per head, the total cost of even a small percentage of cases within a herd is high (see Table 1 ). In a 500-head herd, for example, foot rot would cost $3,000 if just 5 percent (25 cattle) of the herd were infected.

The good news for producers is that vaccination is available for around $2 per head, which means vaccinating the entire 500-head herd ($1,000 in this example) still saves the producer $2,000 annually.

Simple math suggests vaccinating for foot rot makes sense economically when there’s a recurring incidence of disease, even at low levels.

The cost to vaccinate every head still provides producers a positive return on investment, and it’s a good management practice if it reduces the need for antibiotic treatment and discarded milk.

Producers considering vaccinating for foot rot should discuss protocols with their veterinarian, along with best management practices and nutritional support to reduce the herd’s susceptibility. PD

References omitted due to space but are available upon request to editor@progressivedairy.com.

PHOTO : The fact is, simple bruising provides an opportunity for the bacteria to proliferate in the area and cause infection. Photo by Doug Scholz

-

Doug Scholz

- Director of Veterinary Services

- Email Doug Scholz