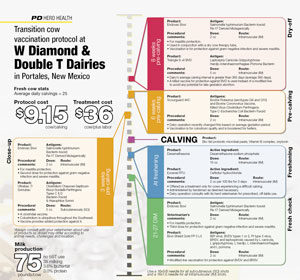

Unpredictable weather is the biggest enemy to herd health for Wes Fraze of Portales, New Mexico, especially for his two dairies’ transition and fresh cow management programs. However, he’s worked with his current veterinarian, Dr. Stevie Smith, to develop protocols that keep his fresh pens – normal weather permitting – “virtually trouble-free.” “From February through May, the wind may blow 30 mph here each day. Or we might get 7 inches of rain in one night,” Fraze says. “Not all of our dairy’s few cow problems are weather-related, but many are.” (Click image at right to open in new window and view at full size.)

Much of Fraze’s success starts with careful attention to dry and close-up cows. Including Fraze, three other employees – a herdsman and both a daytime and nighttime employee – work the dairy’s fresh and dry cow pens.

“We probably spend more time in our close-up pen than anywhere else,” Fraze says. “Basically those close-up cows are only without attention for maybe two hours per day.”

Fraze moves all dry cows to the close-up pen at 255 to 270 days pregnant. Each morning the dedicated fresh cow pen worker locks up all close-up cows to check for those just a few days before calving.

“We’ve been doing this for the last three years, and it has really helped our freshening program,” Fraze says.

After calving, a fresh cow enters one of four fresh pens. If the cow is a Jersey cow from the 4,000-cow W Diamond facility, she goes into an “early” fresh cow Jersey group. And if she is a Holstein or Holstein-cross from the 2,000-cow Double T facility, she goes to one of two fresh cow groups, based on her size. (Crossbred Holsteins and first-calf heifers are a group.)

Smith says the employees do a good job of walking the pens, although Fraze easily admits his protocol isn’t typical. While his herdsman will carry a thermometer with him as protocol, he will not temp every cow.

“It’s the KISS method. We keep it simple. If a cow doesn’t look right, we will temp her and check her,“ Fraze says. “My herdsman will carry a stethoscope to check for DAs, but those are almost nonexistent here. We’re not really aggressive in our fresh cow pen, but we don’t have to be.”

If treatments are necessary for fresh cows, a three-day treatment of ceftiofur hydrochloride will be administered. If she does not improve within three days, the cow goes to the hospital pen for more aggressive treatment.

Smith uses prostaglandin to clean up injured or problem cows during her visits to the dairy at least every other week. However, Smith says she finds the dairy usually has a very low incidence of uterine health issues (.5 percent for Jerseys and 2 to 3 percent for the Holsteins).

The dairy’s voluntary waiting period is 50 days and no timed A.I. program is used. Smith, who also consults the dairy on reproduction issues, says the dairy’s strong fresh cow health program helps get most cows rebred quickly.

“Here they get excellent production, but they are also focused on maintaining cow numbers and having some longevity in their herd,” Smith says. “They’re not pushing for 90 pounds of milk, rather lots of 70-pound-producing cows that are getting bred back and surviving in their system. Everything we do speaks to that goal, and part of that goal is getting them there in a cost-effective manner.”

Fraze admits that this fresh cow program has worked so well that cows stay in the system, and since he hasn’t aggressively culled, on occasion, his fresh, and particularly his dry cow pens, are a bit overcrowded. Building another corral on his 35-year-old facility isn’t an option, so Fraze says one of his transition cow challenges is managing for overcrowding. He thinks close-up pen overcrowding may contribute to more milk fever cases than he desires for his fresh cows.

“We’d have to take away a milk cow pen to fix our overcrowding issue,” Fraze says. “But we are just like everyone else, we don’t want to free up a milk pen.”

Fraze keeps track of his fresh cow program metrics in two ways – mentally daily as he walks fresh pens and treats cows and monthly through his dairy software. For a dairy that freshens 25 to 30 cows per day, he says he gets worried if he has more than two cows per week with milk fever and more than three cows per week treated with prostaglandin. If he is concerned, Fraze says he doesn’t want to overreact and will look at his monthly DairyComp health event records. He consults with his nutritionist and veterinarian before making changes to any protocols.

“We don’t jump to conclusions and make rash decisions,” Fraze says. “We don’t say, ‘We’re having milk fevers. Let’s change mineral companies.’ It’s a thought process for us. We’re confident when we make a change that we know what caused the problem and we’re not speculating about it.”

Fraze and Smith review the dairy’s herd health program and vaccine protocols every three months to evaluate changes in herd health and address any potential challenges.

“Wes is constantly looking at his records, looking at his ration, looking at his cows, listening to his guys and responding to the combination of that information,” Smith says. “That’s not a specific treatment, or drug, or a ration ingredient, but listening to information from all those things, helps maintain overall health.”

Fraze says he appreciates input from his paid “experts in their own field.” He says hearing their feedback is valuable because even though he is on the dairy day-to-day, he often doesn’t notice slow herd health changes, that Smith’s every-other-week visits often catch.

“She’s a new set of eyes,” Fraze says. “You can’t just have blinders on.” PD

Dr. Stevie Smith

Veterinarian

Dairy Production

Veterinary Services

steviesmith831@hotmail.com