Twenty-eight years ago, Charles Owen, a horse farrier by training, began his amazing journey to unlock the mystery of laminitis. Starting with an idea of how laminitis originated, Owen spent the next 17 years researching his theory and another 11 years testing it.

“The feeling is like someone catching their dream,” Owen says. “I believe I am here to help animals, and to see Laminil succeed is beyond my wildest dreams.”

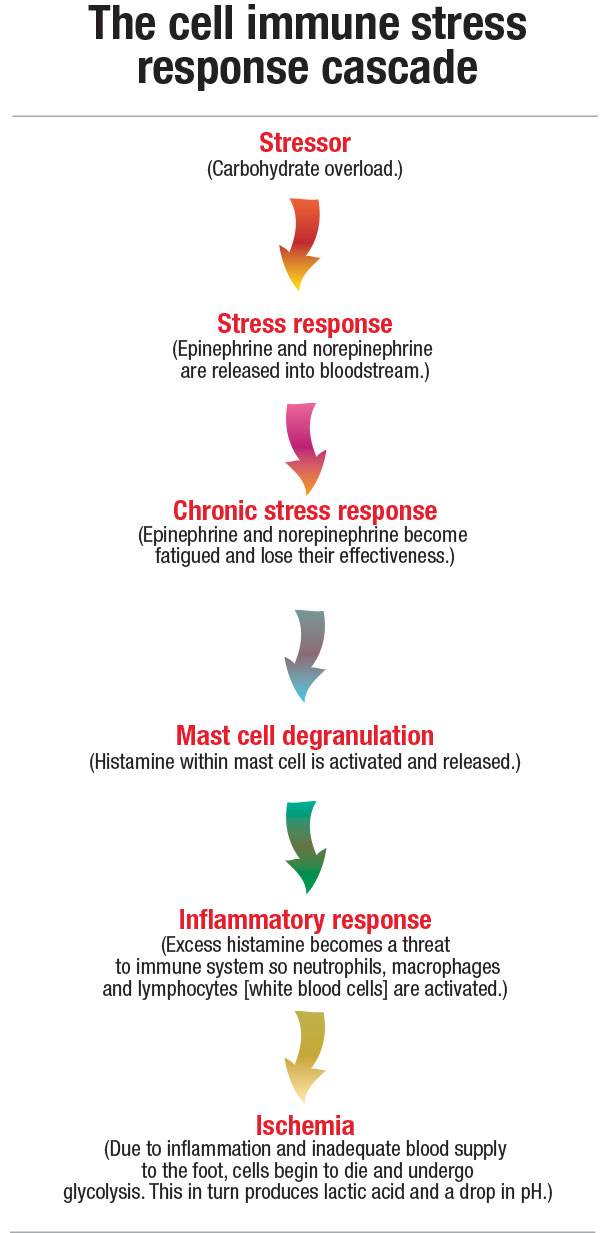

Owen’s whole theory started with cell immune stress cascade, a chain of biochemical events that causes inflammation and leads to laminitis. This cascade begins when the body is upset because it is getting too much of something or something different than what the body can tolerate.

“The cell immune response is activated when there is a threat to homeostasis. When the cow gets too much grain, it upsets the homeostasis of the body,” Owen says. “The body then goes into survival mode of flight or fight, and that is how you get the acquisition of the fermentation process within the rumen.”

Owen believed the laminitis cascade could be stopped at the mast cell. Mast cells play a key role in the cascade by releasing histamine and other inflammatory mediators such as neutrophils, lymphocytes and macrophages.

“The product inhibits the calcium ion activation of the mast cell,” Owen explains. “Without intercellular calcium, the inflammatory mediators contained in the mast cell cannot fuse to the cell membrane to granulate.”

This in turn stops the fermentation process in the rumen and levels pH by preventing lactic acid from being produced. The product works as adaptive immunity, thus allowing the rumen to adjust to the bacteria or excess grain in the diet.

“Let’s say, for example, a cow eats 5 pounds of grain a day and its limit is 10 pounds,” Owen says. “If you started giving it 15 pounds of grain a day, it would get rumen acidosis. However, if you feed my product with the 15 pounds, the digestive tract will adapt to that amount of grain and not get acidosis.”

Owen sees this product benefiting the industry by lowering health costs and allowing cows to be fed higher levels of grain to produce more milk.

The discovery of the product came about after Owen’s initial 17 years of research. He turned to Colorado State University to test his theory that the laminitis cascade could be stopped at the mast cell. When his theory proved to be viable, his next task was to find a drug that would interrupt and halt the laminitis cascade by inhibiting mast cells.

Owens contacted a major hospital that specialized in immune system treatments, and they pointed to a class of drugs called mast cell inhibitors. He tested the compounds in the university laboratory and found that cromone molecules – cromolyn and nedocromil –appeared promising.

“We started in a petri dish and challenged the drug with lactic acid because lactic acid within the rumen is what causes the process,” Owen says. “We then worked with the Colorado State University’s dairy and tested on the cows there.”

For his studies at the dairy, Owen artificially induced the cows into rumen acidosis using oleo fructose. The test cows were given Owen’s product to see if it would relieve or reduce the clinical signs of rumen acidosis. The effects were positive. Owen then moved his tests to anecdotal dairy cows that were compromised by rumen acidosis.

Although laminitis can be caused by grain overload in both horses and cows, it anatomically occurs in each differently. Because the horse does not have a rumen, the horse doesn’t go through rumen acidosis like a cow.

Owen says his product has an 80 percent success rate for curing subacute and acute rumen acidosis. The product is most commonly given as an oral powder, but can also be administered as a pellet, lick, bolus, drench or oral paste.

The product is still in the start-up stage, and Owen hopes to commercialize it in the dairy industry.

“That is why I’m trying to get it into the market now because it doesn’t do any good just sitting around,” Owen says.

He is currently looking for someone to either invest or license the product. Until then, the product is manufactured at Wilocroft Farms in Newberry, Florida, for producers or veterinarians wishing to try the product. ![]()

-

Audrey Schmitz

- Editor

- Progressive Dairyman

- Email Audrey Schmitz

GRAPHIC: Graphic by staff.