Twenty-one countries have eliminated bovine leukemia virus (BLV) from their cattle populations. The U.S. is not one of them. Years ago, it deemed the effort cost-prohibitive.

Today, however, researchers believe the growing prevalence of the virus and new insight into its negative impacts on milk production and longevity make this decision worth revisiting.

What is BLV?

Bovine leukemia virus is a retrovirus of cattle. The virus inserts its genetic material into the DNA of cow lymphocytes – a type of white blood cell with key roles in the immune system. It remains there for the cow’s entire life and may cause disease and be transmitted to other animals.

Less than 5 percent of infected animals develop cancer. These lymphomas commonly develop on the heart, abomasum, uterus, lymph nodes, spinal cord and behind the eyes.

Malignant lymphoma was the most common reason for postmortem dairy cow carcass condemnation by the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service from 2005 to 2007, according to a 2009 Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association article by veterinarians from Washington State University.

Although this may be the most obvious manifestation of the disease, an additional 30 to 40 percent of infected cows have persistently elevated numbers of lymphocytes. The effects of this alteration to the immune system continue to be studied by researchers at Michigan State University, with funding from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

“In my opinion, I think one of the biggest misconceptions [among dairy producers] is: If they’re not seeing BLV-related tumors, then they don’t have a problem with BLV,” says Dr. Rebecca LaDronka, a veterinarian and graduate student at the Michigan State University College of Veterinary Medicine. “BLV is one of those diseases that just because you don’t see it – just because it’s not obvious – doesn’t mean it’s not there or it’s not causing problems.”

How prevalent is it?

A 2007 study by the USDA National Animal Health Monitoring System found bulk tank milk from 83.9 percent of U.S. dairy operations contained BLV antibodies. A 2010 study of 113 Michigan dairy herds found mean within-herd prevalence of the virus was 32.8 percent, and prevalence increased with successive lactations.

A 2015-2016 national survey of 103 dairy herds from 11 states found over 90 percent of herds had at least one BLV-positive cow. Despite this, almost 90 percent of producers surveyed thought BLV was a small or nonexistent problem, says LaDronka.

“Those numbers just don’t line up – it is there even if people don’t see it as a problem,” she says.

What are the economic and health impacts?

Aside from loss of profit due to carcass condemnation and trade restrictions with BLV-free countries, researchers are uncovering the other hidden costs of persistent lymphocytosis.

MSU first began taking a deeper look at the effects of BLV after an incidental finding. In a 2011 article published in Veterinary Medicine International, BLV-positive cows had a decreased antibody response to the J-5 E. coli bacterin vaccine used to decrease the severity of mastitis.

In response to vaccination, B-lymphocytes produce antibodies against an infectious agent, and T-lymphocytes “memorize” it as an agent to attack in the future. Because BLV alters this population of cells, it may impact the immune system and protection against disease after vaccination.

Another concern is early loss of BLV-infected cows. “Cows culled for a wide variety of reasons (poor production, mastitis, lameness, etc.) may have been more severely affected by these problems because their immune systems were not fully functional,” the MSU Bovine Leukemia Virus website states.

A 2013 study in the Journal of Dairy Science examined 3,849 Holsteins in 112 Michigan dairy herds. MSU researchers tracked BLV-positive and -negative cows for 20 months after diagnosis. BLV-positive cows were 23 percent more likely to die or be culled during this time.

“Cows may not peak in milk production until their fifth lactation, and the peak in annual profit may not be until their sixth lactation. Cows this old are increasingly rare on today’s dairy farms, though,” wrote MSU Extension in a 2017 Hoard’s Dairyman article.

MSU researchers are also attempting to quantify milk loss due to BLV.

In 1996, the annual economic loss due to BLV – mostly from reduced milk production – was estimated to be $285 million for producers and $240 million for consumers, according to a USDA National Animal Health Monitoring System dairy study.

The 2015-2016 national survey found each 10 percent increase in BLV prevalence was associated with a 540-pound loss in rolling herd average milk production, according to the 2017 Hoard’s Dairyman article.

“Determining milk loss from BLV-herd prevalence can be complicated because there are many factors that impact milk production,” wrote MSU Extension. “For example, older cows produce more milk, but they also are more likely to have been infected with BLV for a longer period of time.”

LaDronka will also analyze the data from this study to look for associations between the virus and somatic cell counts or reproduction parameters.

“We all know dairy margins are small, and producers need to know the impacts of BLV – even if they’re not obvious – may be eating away at that margin,” LaDronka says.

What can be done?

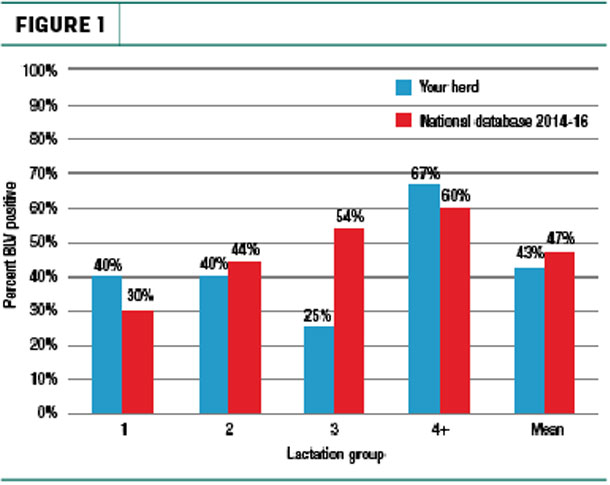

For those producers interested in knowing the prevalence of the virus within their own herd, MSU Extension recommends performing a BLV herd profile. This involves running a BLV enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test on milk from the 10 most recently fresh cows in each of the first-, second-, third- and fourth-plus-lactation groups in the herd (Figure 1).

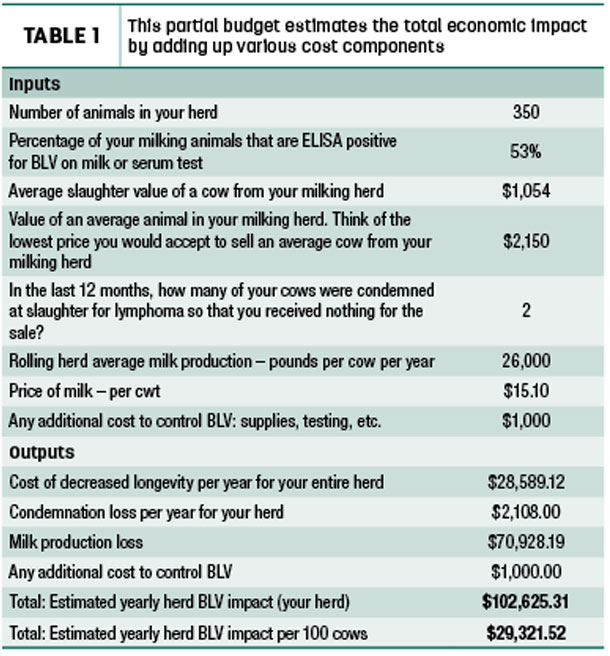

Producers can then calculate the average for each lactation group by inputting their results on a spreadsheet from the MSU Extension website. They can also utilize the website’s partial budget spreadsheet to estimate yearly BLV impact for their herd. This includes cost of decreased longevity, condemnation loss and milk production loss (Table 1).

Producers can then calculate the average for each lactation group by inputting their results on a spreadsheet from the MSU Extension website. They can also utilize the website’s partial budget spreadsheet to estimate yearly BLV impact for their herd. This includes cost of decreased longevity, condemnation loss and milk production loss (Table 1).

Unfortunately, there is no vaccine or treatment to eliminate the virus from an infected cow. To identify viable management options for their herd, producers must consider the prevalence of BLV and which lactation group is most affected.

Unfortunately, there is no vaccine or treatment to eliminate the virus from an infected cow. To identify viable management options for their herd, producers must consider the prevalence of BLV and which lactation group is most affected.

Some suggestions to reduce transmission include improving medical hygiene by changing palpation sleeves and needles, as well as cleaning tattoo and dehorning equipment, between animals.

These tools can pass virus-infected lymphocytes within blood. While this works for some farms, BLV proves to be a difficult virus to tackle, says Vickie Ruggiero, a licensed veterinary technician and graduate student at MSU College of Veterinary Medicine.

“Aside from eliminating practices that are major sources of blood contamination, like gauge dehorning for example, these changes don’t seem to make significant headway in reducing transmission within dairy herds,” she says.

LaDronka has spoken to a number of producers who have tried implementing control measures without reaching their goals.

“I think a lot of that has to do with what we still don’t know about BLV and how it spreads in a herd,” she says.

One strategy utilized by the MSU Pasture Dairy Center at the W.K. Kellogg Biological Station was to cull those cows identified as “super-shedders.” These are cows that have the highest load of viral DNA in their blood cells.

In three years, the center reduced BLV prevalence within their herd from 62 percent to 33 percent. Ruggiero and researchers at other institutions continue to study this management option.

“Future research in this area is planned to try this method in more herds, and we’re working with dairy industry partners on refining testing approach to use faster, more sensitive and less expensive test methods,” Ruggiero says. ![]()