An ideal bedding for dairy cows is clean, provides a certain degree of cow comfort and doesn’t readily support bacterial growth. Sand fits that bill to a tee. Sand-laden manure, however, is the less attractive side of the deal.

Many producers count on recycling the nutrients in manure by spreading it over their land. Those who don’t use their own manure often sell it to someone who will.

Even top-of-the-line sand separators can’t remove all the sand in cow manure, and some sand is inevitably scattered over a producer’s fields.

The subject of whether too much sand is negatively affecting soil health has yet to be thoroughly studied in a practical sense, but soil scientists are clear on one thing: Adding too much of anything to soil, including sand, can change how a soil performs over time. By “time,” they’re talking decades or more.

Iowa State University professor Daniel Andersen, the voice behind “The Manure Scoop” blog, has looked at this issue up close.

“One of the questions I get from people is, ‘If I buy dairy manure, what am I doing to my soil?’” Andersen says.

The answer is complicated, and it largely depends on how much sand-laden manure is being added to soil and how often.

But first, if you look at the manure that comes from dairies, the quantity of residual sand depends on how much sand the dairy recovers for re-use.

Andersen says sand recovery rates vary by dairy: Mechanical sand separators are the most effective, recovering more than 90 percent of sand in some cases, while sand settling lanes and weeping walls may recapture as little as 50 percent of sand – or up to 70 to 85 percent in well-functioning systems.

When farmers consider adding manure to soils for nutrient recycling, it’s generally phosphorus they’re after, Andersen says.

Andersen cites a corn-soybean rotation, for example, where a desired amount of phosphorus would be something like 70 pounds per acre per year.

Andersen estimates dairy manure has about 5 pounds of phosphorus per ton – and maybe 300 pounds of sand per ton if you assume the dairy recovers 50 percent of its sand. (Many will recover more than that.) In other words, a producer gets about 60 pounds of sand along with every pound of desired phosphorus.

At a 4-inch tillage depth, assuming a soil density of 540 pounds per acre, farmers spreading sand-laden dairy manure would be adding about 2 tons of sand per acre each year in this example.

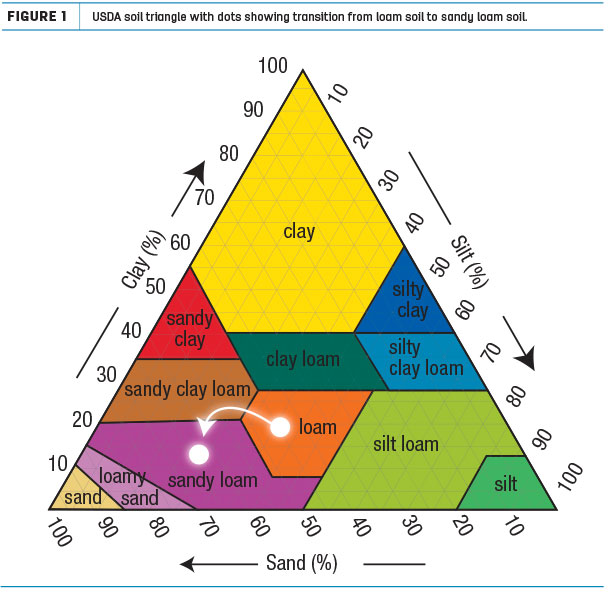

So what’s the effect on soil? Let’s rewind for a moment. Soil has three basic mineral properties – sand, silt and clay. If you start with a loam soil – 20 percent clay, 40 percent silt, 40 percent sand – adding 2 tons of sand changes that makeup to 19.9 percent clay, 39.9 percent silt and 40.2 percent sand.

The change is negligible, Andersen says.

But after 84 years of doing this, the change in soil composition is enough to turn your loam soil into a sandy loam soil (15 percent clay, 29 percent silt and 56 percent sand).

That transition from loam to sandy loam could happen even faster if a farmer’s soil is already on the cusp. Or it could happen slower if a dairy consistently recovers more than 50 percent of the sand in its manure.

For Andersen, adding sand doesn’t necessarily make a soil worse than it was before. He points out many producers lose more soil to erosion than they add in sand, and erosion is the more troubling concern in that case.

Soil management has a bigger influence on soil health than soil composition does, but being mindful of long-term soil health is important, Andersen says.

When talking about a soil’s inherent mix of sand, silt and clay, there’s not a lot you can do to balance those soil elements, Andersen says. But producers who know they’re adding sand to their soils can build their soil health to counteract that effect. Andersen points to cover-cropping as an example.

“Cover crops add carbon to the soil,” he says. “Rye, for example, puts maybe 50 percent of its organic matter in the soil through the root system. Organic matter improves water retention in soil, and that sort of counteracts what sand does.” Andersen states that manure also adds a certain amount of organic matter to the soil, which may help counteract potential harm done by adding sand.

Iowa state soil scientist Rick Bednarek agrees soil management plays a bigger role in soil health than soil makeup. Beyond the physical properties of a soil, Bednarek points to microbial community (the living organisms in the soil) as a hallmark of health. He has two suggestions.

“In order to improve soil health, you have to be no-till, and you have to use cover crops,” he says. A minority of producers use no-till and cover-cropping practices, but a mounting body of evidence suggests these two management tactics have long-term benefits for soil health, especially in bolstering a soil’s microbial community.

“The most active part [in soil] for microbial activity is around the roots,” Bednarek says, helping to elucidate why cover-cropping matters apart from adding organic matter to the soil.

Bednarek also points out adding sand can be good for some soil types, especially clay-heavy soils. “The purpose of sand in soil is to help with porosity,” which is important to how water makes its way into soil, Bednarek says. Water doesn’t penetrate clay-heavy soils easily and, when it does, clay particles don’t always readily release that water to plants.

Across the country, about 30 percent of dairy cows are provided sand bedding, according to a 2007 USDA study on cow comfort. Straw or hay was the dominant bedding type for nearly 50 percent of American dairy cows.

For most producers, the limiting factor on sand use typically comes down to regional availability and cost.

For dairies that do use sand as stall bedding, soil scientists recommend being mindful of how soil texture can change over time and, perhaps more importantly, how managing proactively for soil health can help mitigate possible negative effects of adding sand. ![]()

Monica Gokey is a freelance writer. Email Monica Gokey.