Depends on whether you want to preserve cosmetic features to maintain resale value and sustain comfort (no one likes sitting on sun-rotted upholstery) and whether or not the weather is severe enough to actually cause structural damage, which could decrease resale value in addition to functionality.

That boat isn’t going to gain any more value than when you bought it; its value will only decline, and the most you can do is try to prevent the declination. You would absolutely protect the investment by some means – tarp, shed or enclosed storage.

What does a boat cost these days, anyway – $10,000? (Those of you who know more about purchasing fishing boats than I do can stop laughing now.) Of course you would protect it.

Now I ask you, what’s a haystack worth? Let’s examine a stack of alfalfa in large, dense square bales (4-by-4-by-8, each weighing 1,600 pounds – for the sake of figuring), four bales high by 20 bales long (80 bales total, which is 64 total tons), and let’s price it at $180 per ton. It’s worth $11,520.

What’s a stack of grass hay worth? Let’s take the same tonnage (64 tons) at a price of $150 per ton. It’s worth $9,600.

Just like that fishing boat, the hay (either alfalfa or grass) will only decline in value. And yet, a quick anonymous clicker-poll at a recent hay association conference indicated 30 percent of growers are not using a cover of any kind (or ground pad) to protect a haystack. Why would 30 percent of the growers choose not to protect a $10,000 haystack?

Measuring losses

Dry matter loss of hay stored in a building results in 1 to 5 percent. So from a $10,000 hay lot, even though a building covered it, we will automatically lose up to $500. Maybe not a huge deal, but there goes the wife’s new dishwasher.

If we store the hay outside on bare soil, it will absorb moisture from the ground and lose from 5 to 20 percent dry matter during a nine-month storage period in the Midwest, and 15 to 50 percent dry matter loss for 12 to 18 months of storage. Now we’re into serious money, and you can kiss that new pickup goodbye.

Glenn Shewmaker, extension forage specialist with the University of Idaho, says, “The extent of storage losses is probably not realized by hay producers because the amount of loss is difficult to measure on the farm unless everything is weighed into and out of storage.”

Hay loses mass and quality over time under any circumstance and in any climate. The challenge is finding a way to preserve mass and quality for as long as possible.

Shewmaker says several factors affect the storage and preservation of high-quality hay: forage species, maturity, harvest management, storage time and management.

Assuming species, maturity and harvest are factors already considered, there are two factors – temperature and moisture – that can increase the rate of decomposition during storage. Large losses can occur in a short period when moisture exceeds 20 percent and temperatures exceed 70ºF.

In this stack of five bales high (Figure 1), with some damage on the bottom bales and the top two layers moldy, about half of the tonnage is of marginal value. If the market for the middle bales was $150 per ton, and the market for the top bales was $75 per ton, the average value of the stack is about $112 per ton. A stack of 100 tons that had the potential value of $15,000 would be devalued to $7,500.

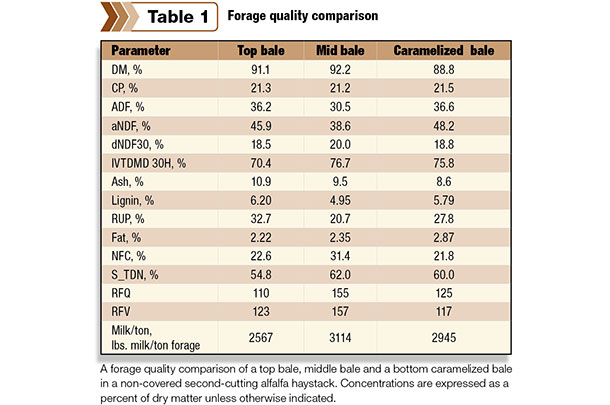

When the top bale, middle bale and a bottom caramelized bale from an uncovered stack were analyzed in the lab for quality, significant differences existed (Table 1).

While not a comprehensive study (so drawing broad statistical conclusions is not appropriate), the quality deterioration is obvious, and the summative total digestible nutrients were lower in the top and bottom bales than the middle bales. In addition, livestock will refuse much of the moldy hay in the top bales.

Shewmaker points out that uncovered stacks in a year with ample supplies and slow demand sometimes lead to unmarketable hay no one wants at any price.

Start with the bale

Shewmaker says densely packed bales and bales laid on their strings shed more moisture than low-density bales or bales placed on edge. If bales must be stored outside, use high-density baling methods. Large bales are more susceptible to initial high harvest moisture than are smaller bales because they retain moisture and retain heat longer in storage.

Dry the hay below 15 to 16 percent moisture before making large bales. Net wrapping on round bales helps bales shed precipitation better than those wrapped with twine. Grass hays with wide and long leaf blades will shed water better than coarse-stemmed hay like alfalfa.

Storage recommendations

First of all, don’t; don’t store it if you can help it. The best option is to sell the hay in the field when quality is best, passing the storage and management costs to the buyer.

The second-best option is a barn or shed, and the more valuable the hay, the easier it is to justify spending time and money to build one. Some states have cost-share programs on facility improvements. On the RG Ranch in Wyoming, Erik Gormley bought steel beams and purlins from a dairy barn being sold at auction and built his own.

Whether an open shed (roof only) or a three-sided barn, these are the most effective for reducing storage losses (down to about 5 percent loss) and set the standard by which other methods are compared. While property taxes will increase with this addition, the overall value of the farm should increase, as well. Those producers wanting to speculate on a rising hay market should consider longer-term barn storage to reduce quality loss.

The next-best option if a barn or shed is not available is to place stacks in sunny, breezy locations on an elevated rock pad and cover with tarps. Plastic sheeting should be at least 6 mils thick; polyethylene tarps have the advantage of allowing moisture to move out of the hay, reducing condensation under the tarp.

Costs of hay tarps range from less than $2 to more than $7 per ton, depending on type of cover and size of stack. Covers also require continual attention to repair tears and re-secure tie-down during periods of high winds.

Shewmaker offers these tips for tarped stacks:

- Stacks should not be more than 24 feet wide.

- Install tarps as soon as possible after stacking.

- Form a peak on wide haystacks before installing the tarp, so water will run off and moisture will vent out of the stack.

- A breezeway under the tarp minimizes condensation under it.

- Long tarps are difficult to handle, so two shorter tarps may be better than one long tarp.

- Prepare the tarp for installation before lifting on top of the stack. A properly folded tarp in accordion fashion is easiest to spread on top of a stack.

- A crew of three works well to install tarps: one person on the top stretching the tarp out and one on each side to tie it down.

- Pull the tarp tight (150 to 300 pounds per square inch tension) and securely anchor it within reach of the ground.

- Tarps should be secured about every 4 feet of length.

- Overlap tarps about 5 feet.

- The stack will shrink over time, so return two or three times during the following weeks to snug the tie-downs. Loose tarps will wear out very quickly.

- As the hay is removed, pull the loose tarp back over the covered portion and tie it securely.

- When finished with the tarp, fold it neatly and store it out of the sun and away from rodents.

- Fold tarps in an accordion fashion so that 3-foot wood tie-down boards stack at each side, neatly lay ropes across the top so they will be covered by the last tarp fold, then fold or roll from each side so ropes are all contained within.

If all else fails, buy a boat

In the same clicker-poll at the recent hay convention, 13 percent of the producers polled used a hay barn, 9 percent used a hay shed, 38 percent used a tarp, and 10 percent used a pad for hay storage. It’s the 30 percent who are not using a cover or pad of any kind that is most concerning.

With recent shifts in weather patterns, those producers might need to invest in a boat to negotiate the lakes between their haystacks. I wonder if they’ll build a shop to store it in? FG

PHOTO 1: Stacking ton bales in the field. Photo courtesy of Mike Dixon.

PHOTO 2: In this stack of five bales high with some damage on the bottom bales and the top two layers moldy, about half of the tonnage is of marginal value. Photo courtesy of Lynn Jaynes.