Dr. Keith Bolsen of Kansas State University several years back introduced the idea of a silage triangle: What is the role of each member of the harvest team during pre-harvest, at harvest or post-harvest that plays a critical role in winning the harvest “war” dairymen face each year?

Whether it’s winter forage, haylage or corn silage, action must be taken by each individual to improve the success of winning the silage war.

Winning, when it comes to harvesting quality feed, means setting up feed to supply the most nutrients toward your herd’s health and milk production.

The goals and what is at stake

A triangle is the strongest shape. It’s no surprise that the people involved often have very strong personalities as well, all with passion for doing the right thing for the client and the cows.

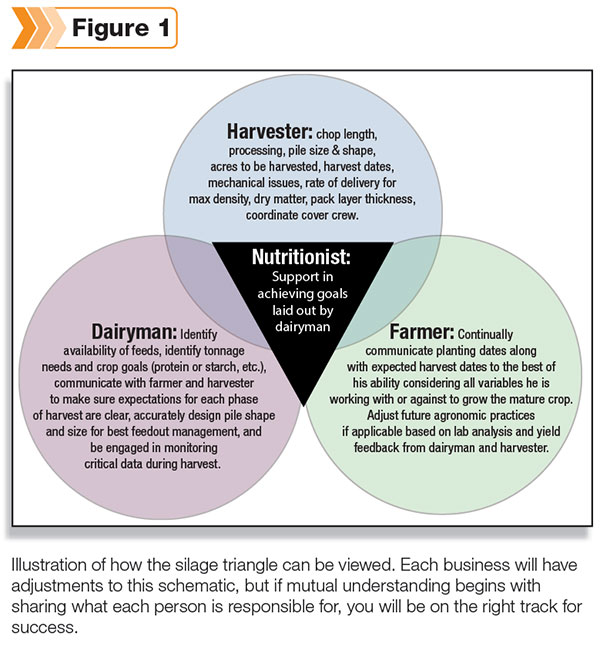

The triangle is made up of the dairyman, harvester and farmer in each of the three points, with the nutritionist often right smack in the middle of it all (unintentionally or intentionally).

The goals of each person clearly should center on maximizing the quality of work and the feed quality for animals.

Much of the success of silage pre-harvest, during harvest and post-harvest boils down to communication or, as I like to say, mutual understanding.

There are rare exceptions, but by and large, the people involved in this triangle did not get into their respective lines of work because communication was their strong point.

However, it’s important we all step back and realize, without this mutual understanding, we couldn’t achieve many of the successes we have on a daily, monthly or annual basis.

There are three main phases of silage making – pre-harvest, during and post-harvest. The farmer, harvester, dairyman and nutritionist each have specific roles during each of these phases but should always be working to make sure each person understands what the others are doing and how their role affects the final product that goes into the ration.

Pre-harvest

During the pre-harvest phase, the farmer needs to communicate planting dates and expected harvest dates to the best of his ability dependent on the obvious variables of weather, variety and irrigation.

During this phase, the harvester should gain complete understanding of the dairyman’s expectations on chop length, processing, pile size and style, acres to be harvested and expected harvest dates.

The dairyman needs to identify available feed, tonnage needs and crop goals (starch, protein, etc.). The dairyman is typically the general in the army of people who will complete all three harvest phases.

He will be the one, in most cases, who will communicate with the harvester and farmer to make sure there is mutual understanding of all expectations in each phase of the harvest.

Dairymen also need to preplan the pile size and shape so feed can be kept as fresh as possible as it moves through the pile.

The nutritionist typically is directed by the dairyman to help bring the goal to fruition. Whether it’s by conducting preplanning meetings, providing tools to calculate value of crop, size or shape of the pile, the nutritionist is an arm of the dairyman during this phase.

Harvest

Phase two is the harvesting phase; the farmer should communicate updated harvest dates, status of crop maturity and expected harvest date changes due to a variety of conditions.

The harvester is monitoring the mechanical side of harvesting quality, such as chop consistency, chop thoroughness, horizontal slice or tearing of stalks and kernel damage (in the case of corn silage).

The harvester is also monitoring dry matter, rate of delivery, pack-layer thickness and all other mechanical issues that play into the final density of the pile.

Density calculators use multiple factors such as dry matter, pack layer thickness, rate of delivery and weight of tractor to generate expected density of the pile.

However, a simple rule of thumb under average conditions of dry matter and 6 to 9 inches of pack-layer thickness is to use 400 pounds of pack tractor for every ton of fresh feed delivered to the pile per hour.

For example, if there are 175 tons of 34 percent dry matter feed delivered per hour, and the pack tractor is packing 6 inches into pile at each pass, your necessary tractor weight would be 175 x 400, or 70,000 pounds.

In addition to focusing on density, the harvester needs to keep open communication with the dairyman and silage-cover crews.

Silage-cover crews can begin to cover the pile that is complete while the remaining portion is finished. Immediate cover improves speed of fermentation and increases potential for higher-quality feed and reduced shrink due to spoilage.

This does not mean the dairyman is on autopilot in this phase; the best dairymen are engaged in monitoring data during harvest.

This is the point where the dairyman is investing mega-dollars for the year’s feed supply; the challenge is to coordinate the army of people to capture the full potential of the harvest.

For example, if a 2,000-cow dairy puts 20,000 tons of feed up at $85 (grown, harvested, covered, shrunk), he has a $1,700,000 investment.

How much he, as the leader, actually captures is directly related to how organized his team is. Here the nutritionist is again an assistant to the dairyman in monitoring the harvest data and is available for on-the-fly decision-making when plans change, and they inevitably will change.

Post-harvest

Phase three is the post-harvest period. Post-harvest is still a time to keep the farmer involved with feedback on lab analysis of the crop and yield per acre.

He will then need to evaluate his agronomic practices or identify strengths and weaknesses in his program that allowed such results in the crop quality and quantity. Keeping the farmer involved is important for future crop quality improvements.

Like the farmer, the harvester has done his work in harvesting and packing the silage but should also be collecting feedback for future silage harvests.

Feedback centered on how well the goals were met for rate of delivery, dry matter, shape and size of pile are all important data for the harvester to know.

In addition, during phase three the harvester can test for density and processing, which will provide guidelines for future harvests.

This phase is the most interactive for the dairyman and his feeding crew. Now is the time that the work of the farmer and the harvester will be put to the test on the feeding-center theater.

During the final phase, the dairyman will need to focus on managing the pile for minimal shrink. By using facing tools or otherwise reducing oxygen exposure loss through poor feedout or poor plastic management, the dairyman will win or lose the silage war.

Here, the nutritionist may be called on to help monitor feedout practices, along with quality changes, so the stored feed can be optimally incorporated into rations for highest efficiency of milk conversion.

Ultimately, the silage war is a war worth fighting. For the farmer, his reputation and income depend on winning or achieving the mapped-out goals as a member of the silage team.

Likewise, a harvester’s income and reputation live and die by the quality of work and the ability to understand the goals set by the dairyman.

For the dairyman, the economics of winning this silage war are twofold: He has to replace what he doesn’t capture in silages in his ration (added expense), and he has loss of milk production efficiency, which can reduce milk flow (loss of income) if the goals are not met.

Finally, for the nutritionist, his client’s viability and longevity are at stake along with his reputation for thoroughness and quality of service. Each point of the triangle has something worth fighting for or something at stake.

When the dust settles and the goals are accounted for, we would all like to say we did our very best to plan and each member of the triangle has understood the expectations, delivered results and reduced any risk exposure that would jeopardize livelihoods or losing the silage war.

I encourage you to start small and set up your next harvest for more success than the last. Win one battle at a time. FG

PHOTOS

PHOTO 1: Modified drive-over pile where two pack tractors are handling feed coming in slowly from the field. Pack-layer thickness and rate of delivery play the largest role in achieving high density and quick fermentation. This pile will be fed at 1 foot of face per day, which is the industry best management practice.

PHOTO 2:

For the dairyman, the economics of winning this silage war are twofold: He has to replace what he doesn’t capture in silages in his ration (added expense), and he has loss of milk production efficiency, which can reduce milk flow (loss of income) if the goals are not met. Photo provided by Luciana Jonkman.

Luciana Jonkman

Nutrition and Management Consultant

Progressive Dairy Solutions Inc.