As a party who supplies hay, grain or other feed or production inputs to a farm, ranch or dairy, you can be in the position of providing credit. When banks extend credit lines for feed, equipment or livestock, those are secured by collateral in the item purchased or other property.

Collateral is real or personal property owned by the borrower that is pledged to the lender as security for repayment. A producer providing feed such as hay to a livestock operation may also be in the position of providing “credit” if they are planning on the feed being paid for after delivery.

Is a handshake good enough?

In agriculture, traditionally farmers have trusted the other party in a transaction. In those cases, the recipient of the commodity (contractor) is not providing any special protection to the farmer supplying the commodity (creditor), such as a security interest or payment contract.

Those creditors are unsecured because they delivered certain items such as feed or livestock for which they do not have any property as security against the balance owed.

When times are good financially, this arrangement seldom has problems with repayment. When times turn tough financially, the contractor may have difficulty repaying some or even all of his creditors, secured and unsecured. Unsecured oral arrangements lack the specificity to cover each party’s responsibility when things do not go as planned.

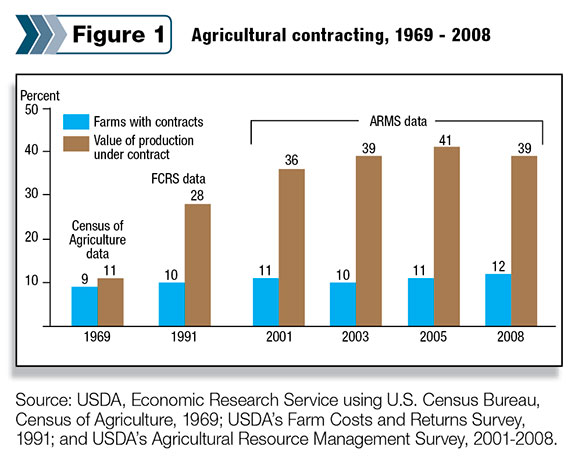

According to the USDA, contracts covered 39 percent of the value of U.S. agricultural production in 2008, 41 percent in 2005, 36 percent in 2001, 28 percent in 1991 and 11 percent in 1969.

The decrease between 2005 and 2008 is largely due to higher prices for commodities less reliant on contracts.

Contracts covered 90 percent of poultry and sugar beet production and 68 percent of hog production in 2008.

Are oral agreements legally binding? It depends …

Whether an agreement is legally binding is dependent on the particular circumstances. The basic points required for any contract are the contract offer, the acceptance of the offer and an exchange of something of value (hay delivered in exchange for money).

In addition, under the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), sales of goods for $500 or more are not enforceable unless there is either a writing signed by the parties to be bound or a written confirmation. A writing would state the essential terms of the agreement such as price, quantity and delivery terms.

A written confirmation would consist of a letter sent by one party to the other outlining the terms shortly after agreement is reached. The other party normally needs to respond with any objections within 10 days in writing, or else the oral agreement is usually enforceable.

The law and regulations governing transactions are guided by the UCC or the code. The UCC, first published in 1952, is one of a number of uniform acts that have been promulgated in an effort to harmonize the law of sales and other commercial transactions in all 50 states.

The UCC consists of 11 articles. Article 2 is the most applicable to commercial transactions in the agricultural context. Article 2 of the UCC governs the sale of “goods,” which is defined as “all things that are movable at the time of identification to a contract for sale.”

What is a security interest?

Article 9 of the UCC governs secured transactions. Secured transactions are an integral part of production agriculture because large amounts of credit are often needed, and lenders often provide agricultural producers credit that is secured by collateral such as crops or livestock.

Having an agreement using personal property as collateral (i.e., forages), should provide a stronger legal position than an oral agreement as outlined above. Under UCC’s article 9, certain tangible personal property such as machinery, livestock or crops can be used as collateral.

A security interest is defined as “… a property interest over specific assets that secures performance of an obligation, typically the payment of a debt. The security interest is typically created though a document known as a security agreement and signed in conjunction with the execution of a promissory note or another loan document.”

A security interest may be created when the contractor needs to borrow funds and the item (i.e., hay) is given as security. It can also be created when the contractor doesn’t have funds to pay the full price for the purchase, and the seller or creditor provides financing while retaining an interest in the property. This is referred to as a purchase money security agreement.

To be enforceable, it must be attached to the collateral. For that to occur, the creditor (lender) must give value (hay), the contractor (debtor) must have rights to the collateral, and the contractor must authenticate an agreement that contains a description of the collateral.

Other terms may apply, such as a restriction on the contractor’s ability to sell the collateral or how the payments are to be made. In some cases, the creditor may retain possession of the collateral. Other legalities may apply to complete the process of creating a security interest. It is best to consult legal counsel when considering such a program.

What is an agricultural lien?

The UCC carves out state statutory agricultural liens that secure payment or performance of an obligation for goods or services furnished or rent on real property leased by a farmer in connection with a farming operation. The perfection and priority of these liens are governed by the specific state lien statute, not the UCC.

These liens can be enforced when the farmer fails to perform any obligation owed to the lienholder. Lien laws vary by state, and the application to agricultural commodities may not be as clearly defined in all states. One should check with the state attorney general’s office for specifics regarding a specific situation.

In many cases, information on agricultural liens is available from the attorney general’s website. Things to look for include a lien type, who is defined as a claimant, what property can be attached, filing deadlines, when the lien would be attached to what property and the lien’s priority versus other claimants. In many states, for a commodity like hay the lien can only attach to the specific commodity delivered by the claimant.

In practice, that would require identification of the actual hay delivered, not hay that happened to be on the user’s premises. In other situations, a feed lien may attach to the livestock being fed. The National Agricultural Law Center (www.nationalaglawcenter.org) has good basic information under their state law clearinghouse menu on liens.

Summary

Although agriculture has a long tradition of conducting business on a handshake, the business climate is undergoing change, and the recession of 2008 – 2009 has forced everyone to be more cautious in business dealings.

Agriculture has been shifting to more written agreements in place of the familiar handshake as operations grow larger and become both geographically and personally more distant. While the unscrupulous are few in number, tough economic times can lead even the very well- intentioned to a situation where repayment of obligations becomes difficult.

This dictates that buyers and sellers should be very prudent in their approach to conducting business. In the case of contracts, security interests and liens, sound legal advice on the nuances of the law will benefit all concerned. FG

What I LEARNED

As I was giving this article a last read-through before print, a question came to mind and I asked the author for clarification. To wit:

Jaynes: Do I understand this right – if I sold hay to a buyer and he didn’t pay but had already fed the hay I sold him to his cows, then I could attach a lien to the livestock being fed?

Gray: Yes, BUT only in some jurisdictions. That is very dependent on state lien law, which varies considerably. A few states allow that but most don’t. The lenders have fought that, as it puts the hay seller ahead of them on the collateral.

Jaynes: So if my state does not allow a subsequent livestock lien, then I have nothing to lien at all?

Gray: Not once “your” feed is used.

So, sure enough I went to www.nationalaglawcenter.org and clicked on my state. Turns out Idaho cannot lien cattle to recoup hay sales but, for instance, Wyoming can. Find out what your state allows.

References omitted due to space but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

C. Wilson Gray

District Extension Economist

Twin Falls R&E Center University of Idaho