This past summer, my agriculture intern and I set out to help Madison County, Kentucky hay producers gather information to answer those questions. Our applied research project consisted of farm visits to 30 local beef cattle and hay producers.

Using a set of portable scales and a tape measure, we randomly weighed three bales and made bale measurements for each lot.

Hay samples were collected using a Colorado hay probe and sent to the Kentucky Department of Agriculture (KDA) for testing.

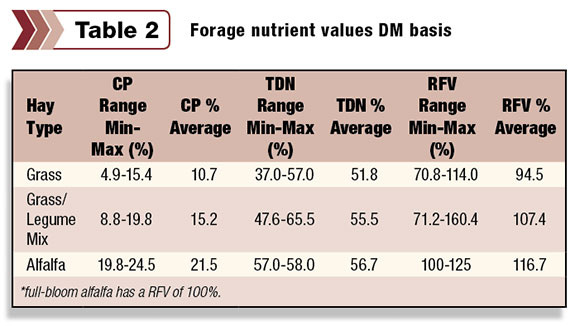

Three categories were used to describe various types of tested hay within our sample group: grass hay, grass/legume mix hay and alfalfa hay. Data was compiled using simple averages.

One factor many hay producers do not consider when determining their selling price is nutrient replacement cost. Hay which is harvested from a field not only provides a feed source for livestock but also is a mechanism of nutrient movement off of the field. Plant nutrients, mostly N, P and K, are removed after each hay cutting.

A significant portion of our hay production costs are related to nutrient replacement. In most cases, soil fertility levels may not need adjusting every year to compensate for removal, but as hay harvests continue over a period of time, fertility levels decline and forage growth will ultimately suffer.

The replacement cost of nutrients should be considered as we seek to establish a price for our hay. Sometimes our asking price may not even cover replacement fertilizer costs, not to mention other expenses such as fuel, twine or net wrap, machinery repairs and labor.

Since the majority of cool-season grass hay produced on farms in our project was comprised of tall fescue, we can utilize those nutrient removal rates to determine fertilizer replacement cost.

Average nutrient removal values per ton of fescue hay are: 35 pounds of N, 18 pounds of P2O5 and 50 pounds of K20. Fertilizer sources and prices used to determine replacement costs were urea at $795 per ton, DAP at $635 per ton and muriate of potash at $645 per ton.

For our group of hay producers, the average bale weight and nutrient replacement cost for a given size bale is listed in Table 1.

A substantial variation in bale weight by type existed for each of the four sizes in our study.

The most dramatic illustration is evident in the five-foot-by-five-foot category, with a 665 pound range between lightest and heaviest bale within that group.

Several of our cooperators were surprised at their actual bale weights, as they found their “best guess” to be way off the mark.

Most of the bale weight variation was due to pressure settings on the baler, driving speed while baling, windrow size and moisture content.

Obtaining an accurate bale weight is critical for setting a fair price when buying or selling hay and for assessing hay needs for winter livestock feeding.

Perhaps the most revealing information producers received came from their hay test results.

Average test values for crude protein (CP), total digestible nutrients (TDN) and relative feed value (RFV) are listed in Table 2.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of forage testing for a livestock or hay producer.

Guessing at nutrient content based on smell, color and texture can be misleading. In order to balance a feed ration for livestock on a forage-based diet, an accurate account of nutrients supplied by the forage is needed.

If we know the nutrient status of our forage and the requirements for various classes of (in our case) beef cattle that we are feeding, then we can determine how much, if any, supplementation is needed to reach a particular performance goal.

Table 3 outlines nutrient requirements for four classes of beef cattle. Hay test results give us important information for use in balancing a ration.

Among the most utilized are crude protein (CP) and total digestible nutrients (TDN).

Results from our hay testing data indicate that the average grass hay will supply adequate nutrition for dry cows in their middle third of gestation.

Our average grass-legume mix hay will come close to supporting a 1,200-pound cow with average milk, and our alfalfa would supply almost enough nutrition for 1,200-pound nursing cows with average milk.

None of these forages alone will meet the TDN needs of a growing 600-pound calf gaining at 2.5 pounds per head per day or a 2-year-old heifer at peak lactation.

As you can see, depending on the type of cattle being fed, some of the hay in this sample set will need to be supplemented in order to meet nutrient requirements. Most of the time, TDN is more limiting in hay than CP.

This was true of our sample set and will also apply on the farm. Simply targeting the CP requirement is not enough. Do not forget about TDN needs as well.

Ultimately, performance, growth and body condition are the final indicators of a cattle feeding program, but the basis of a balanced ration begins with forage testing. FG

Mat Thomas is an agriculture intern with the Madison County Extension of the University of Kentucky.