This score, which allocates points for performance in different management areas, can be beneficial to herds wishing to evaluate their performance year after year or to benchmark themselves against other herds.

The planning committee of the 2018 Western Canadian Dairy Seminar invited three dairy producers who have achieved a high score to discuss their farms and the management strategies they follow.

Cees Haanstra, Chris McLaren and Dave Taylor talked about what works well for them during a panel presentation on March 8 in Red Deer, Alberta.

Cees Haanstra

Greiden Farms Ltd.

St. Mary’s, Ontario

Haanstra; his wife, Hinny; and two full-time employees they helped sponsor arrived in Canada from the Netherlands in January 1992. They purchased a 200-acre cash-crop farm and built a barn for 120 milking cows plus dry cows and replacement heifers.

They also rented 200 acres to farm, focusing more on purchasing quota than purchasing land. “Quota cash flows better than buying land,” he said.

After expanding every couple of years, Greiden Farms Ltd. now owns 1,750 acres, rents 250 acres, milks 640 cows and holds 960 kilograms of quota. The Haanstras also own some related companies.

Uniondale Farms Ltd. is a cropping company where they do everything from manure hauling and planting to harvesting. Located in a prime area of dairy country in Oxford County, the land is expensive, and the Haanstras try to get the most from every acre.

The cropping rotation includes 550 acres alfalfa, which is followed by edible beans, soybeans and winter wheat.

They double-crop with barley, oats and peas, which are no-till planted into the wheat stubble and harvested in October. It is chopped and used as feed for the dry cows and heifers.

They also have 350 acres of corn for silage and 500 acres of corn for grain.

Laurian Farms Ltd. is their heifer facility down the road from the home farm. This four-row freestall barn has a tail-to-tail design with rubber mats and sawdust as bedding.

It has an automated manure scraper, headlocks for handling and breeding, and an automated feed pusher since they are not there all day long. Feed is delivered mixed from the home farm once a day.

Maple Corner Farms Ltd. is a hog facility where they currently rent out the building but farm the land and utilize the manure. As part of the farm’s succession plan, they plan to build a dairy facility here for their oldest son, Arjan.

Cees, Hinny and Arjan are all involved on the farm, as is the second-oldest son, Rolf. They have two more children who are not interested in joining the farm. To help with the workload, the farm has six full-time and four part-time employees.

At the home farm, they continue to use the original dairy barn built in 1992, but it has had a few expansions.

The barn is a four-row, tail-to-tail freestall with automated alley scrapers, headlocks, a sprinkler system on the headrail and lots of fans.

The dry cow barn on the south side has two different groups – close-up and far-off. They use deep-bedded sawdust because the barn is not set up for sand. It is a slatted-floor barn with an automated scraper that runs over the top.

The scraper is turned off at night in case a cow should calve suddenly in the freestall before she could be moved to the straw-pack calving pen.

They milk 3X in a double-11 parlour with one person milking and another person bringing up cows and sorting those that are in heat.

They are averaging 43 to 44 litres of milk per cow per day with 3.96 fat and 3.12 protein. Somatic cell counts are 80,000 to 120,000. Haanstra said SCC is running a little higher now due to having a higher concentration of grass in the alfalfa silage last year.

The pregnancy rate is 26 percent, age at first calving is 23 months, calving interval is 13 months, longevity is 42 percent and turnover rate of 38 percent. Their Herd Management Score dropped to 928 from 952 in 2016, mostly due to longevity.

“We milk 100 cows more than the year before,” he said. With the quota increase and purchasing more quota, they have to milk more cows. Percentage-wise, it is a younger herd.

In addition, they have a high selection of new heifers coming in to the herd, so they are culling cows pretty heavily.

The farm has nine bunker silos for haylage, corn silage, high-moisture cob meal, beet pulp and wet brewers grain.

High-moisture corn is stored in a Harvestore silo, and they have a commodity shed behind the barn.

Roasted soybeans, chopped wheat straw and calf pellets are kept in the feed room behind the barn.

Haanstra said he likes feeding beet pulp because it has less starch and more palatability, which increases feed intake.

They will premix the ration the day before so only corn silage and haylage needs to be added in the morning.

All milking cows get the same ration, except the fresh cows, which also get chopped hay, beet pulp and a transition mix. Milk cows are fed once a day, and feed is pushed up four times a day.

Close-ups are fed wheat straw, corn silage, beet pulp, pre-mix minerals and some haylage once a day.

Far-off dry cows get chopped wheat straw; the barley, oat and pea silage; corn silage and minerals. They are fed every other day along with the heifers at the home farm.

Breeding protocols include weekly herd health checks for heifers and cows, activity transponders, a 55- to 60-day voluntary waiting period and an Ovsynch program supported with progesterone intravaginal devices.

In terms of genetics, Haanstra said he looks for high milk potential and good components, a high focus on udders and feet and legs, as well as health traits and fertility. He is using top sires and genomic-tested bulls.

To maintain hoof health, footbaths are located in the return alleys and are filled automatically with copper sulphate and formaldehyde. The same solution is used for the automatic footbath at the heifer barn down the road.

Haanstra does most of the hoof trimming, which is done every day. All cows are trimmed before drying off. New fresh heifers get a trim, and he keeps up on maintenance trimming.

He said they started using the X-Zelit program and have noticed fewer troubles with transition. They used to give all of the second- or greater-lactation cows an IV. They no longer give IVs and instead give older cows a calcium bolus and a 50-cc injection. “It’s not that cheap, but it works very well and saves us a lot of time,” Haanstra said.

Pre-calving, the cows receive a Rumensin bolus, selenium booster and scours vaccine.

At birth, they disinfect the calf’s navel and give selenium. Colostrum is checked for quality, and the first two feedings are done with an esophageal tube.

The calf barn is a roof over hutches. There is a concrete scrape alley, and the hutches are over sand with straw for bedding. Whole milk is fed via pails with nipples, and they aim to wean at 8 weeks old.

For the future, Haanstra’s ultimate goal is to have a good transition to the next generation. They have purchased five robots for the new dairy farm and were in the process of finalizing the drawing and securing permits. He would also like to achieve a herd average of 50 litres.

He said his secrets to success are in watching the details, hiring good employees, training employees well, adhering to protocols and believing in your own dreams.

Chris McLaren

Larenwood Farms Ltd.

Drumbo, Ontario

McLaren is the sixth generation on his family’s farm. Six years ago, they moved the milking herd into a new sand-bedded freestall barn, which he credits as “the catalyst to some of our successes.”

McLaren, along with his father, Grant, and uncle, Dan, focused their efforts on genetics and management in the old barn, and yet progress seemed to be at a standstill for five to 10 years.

“Once we moved into the new barn, it kind of got things rolling,” he said.

His father and uncle are officially retired now but still help around the farm, which has 110 milking cows and 600 acres.

Milking and dry cows are housed in the new facility. There are three milking groups – fresh, heifer and mature.

They have a double-10 parlour with AfiAct II for lying and activity information, as well as AfiLab for butterfat and protein levels on every cow at every milking. The herd is averaging 40 to 45 litres per cow per day at 2X milking with 3.9 fat. The BCA is over 300 most of the time.

“We pride ourselves in having 50 percent Very Good or Excellent in the barn as well,” he said.

Somatic cell count is around 100,000, but they’ve been as low as 50,000. For most diseases, the herd is in the 5 percent incidence range.

Due to recent challenges, the pregnancy rate is at 17 percent, where it used to be 25 to 30 percent. “It’s not all roses on farms,” McLaren said. “There’s always struggles.”

Genetics is one of the most important decisions on the farm to make sure they produce a cow that will survive a long time. “We believe in a balanced approach between type, production and health, with more emphasis on health,” he said. McLaren relies heavily on genomics and top-genomic bulls. The top 15 percent of heifers are bred with sexed semen.

At birth, calves are fed colostrum as soon as possible. They are also given selenium injections, Halocur for crypto prevention, a navel dip and a calf coat if it’s cold.

Calves are housed in outdoor hutches and fed whole milk twice a day. They will get a third feeding in cold weather and free-choice water all year long. At 6 weeks old, the amount of milk offered is cut in half. By 7 weeks old, calves are weaned but remain in their hutches for one more week before they are moved to group housing.

McLaren also monitors starter intake and, if the calves aren’t eating 2 kilograms of starter at weaning, he will hold them back until they reach that goal.

“We try to avoid multiple stressors on calves at any one time. If we’re going to wean a calf, we’re not going to dehorn or do ration changes at the same time,” he said.

After weaning, calves move into an old implement shed, which has been converted to a pack barn, and split into four groups. The young heifers are fed milk cow refusals with top-dressed grain and protein to meet the needs of each group.

From 6 to 8 months old, until they are confirmed pregnant, the heifers are fed grass silage, a cheap feed with 15 percent protein when harvested correctly. He no-tills rye into corn silage ground and sows oats into the wheat stubble.

Heifers are bred at 13 months old with 99 percent of breedings based on SCR Heatime.

They are housed in the old freestall barn with deep-bedded straw and access to the outside until they are confirmed pregnant and move to the new barn.

McLaren said he focuses a lot on prevention and identifying problems when they are small to address them before they limit production. “I would rather spend my money on vaccination, prevention, management and overall facilities than on a bottle of antibiotics,” he said.

For vaccinations, he gives calves Inforce at birth and weaning, and boosters it with Express 5 at 6 months, 12 months and during each lactation at 30 days in milk.

He uses a blanket dry cow treatment program with Dry-Clox and Orbeseal teat sealant. Cows also get ScourGuard and Enviracor J-5 at this time. He targets a 60-day dry-off period for heifers and shortens it to 50 days or fewer for older cows if they are milking well.

At 21 to 28 days close-up, cows get a Rumensin bolus, J-5 and ScourGuard. Once in the pre-calving pen, they receive selenium, Vitamin AD and Imrestor.

After participating in a research study three years ago, he found there were a lot of cows with subclinical hypocalcemia. Now every cow in its second lactation or greater gets a shot of calcium, and third-lactation-or- greater cows will get a second shot 24 hours later.

“That transitioning has been fantastic,” he said. “Milk fevers are nearly nonexistent.” The cows get Imrestor again at calving and a J-5 booster about a week later.

He also has an aggressive ketosis monitoring program. When first moving into the barn, 30 to 40 percent of the cows were found to have ketosis. Now cows are tested with Keto-Test the first three to 16 days, and anything over 100 µmol per litre is treated with glycol immediately for three days.

They are tested again, and the treatment is repeated for another three days as needed. In between this weekly test, he will watch for high butterfat-to-protein ratios and test again as necessary.

McLaren also collects locomotion scores early in lactation to help pick which cows to present to the hoof trimmer, who comes to the farm every six weeks. Cows are maintenance trimmed at 100 days in milk and before drying off.

The farm is battling a bit of strawberry foot rot or digital dermatitis and is using an automated footbath with 2 percent formaldehyde at every milking.

After the voluntary waiting period of 60 days, most cows are bred based on activity. If found in estrus at 70 days or open at recheck, he will implant a CIDR.

The herd is fed once a day. Milk cows receive the same ration, except fresh cows get a little more yeast and roasted soybeans. He recently invested in a feed pusher to push up feed eight times a day.

“I’ve really noticed the advantages in the dry cow group with 10 to 15 percent more intake by pushing feed up more often,” he said.

He feeds a one-group dry cow ration high in straw and hay with a little yeast and roasted soybeans.

McLaren said his secrets to success boil down to details. First of all, he likes to keep everything the same all of the time. When things get off schedule, it shows in dips in lying time.

He also tries to avoid social stressors by moving cows in pairs whether as calves or moving out of the fresh group.

Cow movements are done once per week, and he keeps subordinate cows in the heifer group to maximize their dry matter intake. All treatments are conducted away from the freestall area and parlour to keep cows relaxed in those areas.

He will remove cows in heat immediately. “I’d rather have one cow down in milk than an entire group of 50,” he said.

McLaren relies on information from his advisers and staff. He also attends meetings, talks with other producers and gets involved in research to keep learning.

Looking to the future, he wants to continue to breed for a high-type, high-production and trouble-free cow. He also wants to improve the farm’s heifer facilities.

Dave Taylor

Viewfield Farm

Courtenay, British Columbia

Taylor’s grandfather immigrated to Canada and worked for a lot of dairy farmers before starting his own farm in 1946 on Vancouver Island.

His father grew the farm to become the biggest on the island. In the late ’70s, he decided to diversify and entered the whole-market garden industry.

He struggled with the high interest rates in the early ’80s but was able to negotiate a sale that allowed him to walk away with 20 cows, 10 heifers, 500 litres of quota and start again.

“What I learned from my dad is to persevere. It’s because of his perseverance my brother and I are farming today,” Taylor said.

His background involves family, 4-H, church, attending university and working in banking for four years before the family purchased a little bit bigger farm in 1995 at their current location in Courtenay, on the central east coast of Vancouver Island.

Taylor farms with his brother Will, and their dad is included in everything they do. “That’s, to us, what succession is about. Even though he’s not an owner, he’s a big part of our farm,” he said.

They are milking 135 cows with an average milk production of 33 kilograms per cow per day, 4.3 percent fat and 3.4 percent protein.

They are breeding with roughly 70 percent proven sires and 30 percent genomic. The farm is fully registered, and they do classify their animals.

When they started at the new farm, they merged their dad’s 40 cows with a grade herd and started registering the new cows on a percentage basis.

At their first classification, they had nine Fairs. The farm’s most recent classification in late February resulted in a 5E cow moving to 6E, three new Excellents and five Very Good first calvers.

“We’re pretty proud of where we’ve come as a herd over that time and kudos to genetics and the advancement of genetics,” he said.

They have an older double-six herringbone parlour where they milk twice a day. Cows stay in an old post-and-beam barn with deep-bedded stalls.

They keep a 1-to-1 ratio of cows to stalls, but he acknowledged the stalls are a little smaller than the current recommended dimensions.

There is a deep-bedded pack hospital area which holds 15 cows comfortably. It is home to fresh cows, lame cows and a couple of older cows.

Calves are housed in hutches for three months. Then they are outside for 10 days to halter break and wean them at the same time.

From there, they move into a recently upgraded heifer facility with six different-size groupings. They stay here until close to calving, when they move to the calving facility, which can house about 12 to 15 animals at a time.

Taylor said they don’t have enough feedbunk space on the farm. They feed a TMR with local grass, corn and purchased processed grain. For the first time in 23 years, they had to buy some alfalfa after armyworm devastated their final crop of grass.

They own 220 acres of land with 180 arable acres and then rent some additional land. They can grow four crops of grass on their land with buried irrigation and two, maybe three, crops on non-irrigated land. The feed is kept in bags.

On part of the farm, down by the river, they operate a private campground where groups can bring in up to a couple of hundred people and enjoy the space. The Taylors do this to give back to the community and educate people about their farm.

Labour is mostly family along with one part-time milker and a “do-whatever-is-needed” guy who has been with them a long time.

Taylor said they use the Herd Management Score, not as a way to benchmark to other farms, but to see improvement in their farm from year to year.

One of their strengths is milk quality, and they get a maximum score of 150 in udder health.

Over the past year, the farm reached its lowest somatic cell count of 35,000 in September and topped out at 69,000 in July. There’s also been a couple of times on DHI test when they did not have any cows over 200,000.

“We take great pride in that,” Taylor said.

They use kiln-dried bedding and add hydrated lime every time they bed the stalls. They also California Mastitis Test all fresh cows for the first two or three milkings just to make sure there are no problems.

If there is a problem, the cow is treated as soon as colostrum is harvested for the calf. He said most of the time they can cure it after two or three treatments.

Any cows treated for mastitis are housed in a separate pen and not reintroduced to the herd until they are doing well. They will also cull chronic cows.

All milk cows are vaccinated with J-Vac and treated to reduce flies. They use selective dry cow treatments on cows that have a high average cell count. “For us, that would be less than 10 percent of cows. We’ve been doing that for five years and see no negative effects,” he said.

They maintain consistency in the process of milking cows, ensuring everyone always follows the same routine of pre-spray with iodine, thorough wipe, attach and post-dip. They also have an iodine backflush to rinse the machine in between cows.

They also max out their Herd Management Score for calving interval and herd efficiency. To get cows back in calf, if one doesn’t show heat within two weeks of the 60-day waiting period, they will give the cow an injection and then have a vet palpate it a few days later to determine the next step.

“It’s probably not as good as Ovsynch programs, but we use a lot less hormones,” Taylor said.

They also focus on problem-free calvings, good feed, proper foot care and good observation of the cows.

“To me, it’s about getting cows back in calf,” he said. “That’s really important because it gives us options. If we calve those out successfully, we can either grow our production, maintain our production, sell cows to other dairies or cull cows from the bottom of our herd.”

He would like to improve the farm’s 25-month age at first calving. They’ve been working at it over the past year and are breeding at 13 to 14 months old.

For longevity, they are right around 40 percent. The 90th percentile for this category is around 46 percent, and he said they aren’t too concerned about this.

Milk value is where they struggle the most. They have some limitations in terms of facilities, but he said they could probably push the herd a little more if they wanted to do so.

There is room to feed more grain, but they don’t want to jeopardize health. They could feed alfalfa, but at $370 a ton to get it to their part of the island, it is costly.

They could milk three times a day, but he said they just don’t want to. One avenue they are considering is to modernize the barn, which could definitely change their score, he said.

Some of the farm’s secrets to success are to play to their strengths and then develop strong partnerships with veterinarians, nutritionists or mechanics who can fill in any weaknesses.

They also look to mentor the next generation so they can use the information and technology of today to do better than previous generations. “Let’s give them the opportunities to go further than we have done,” Taylor said. ![]()

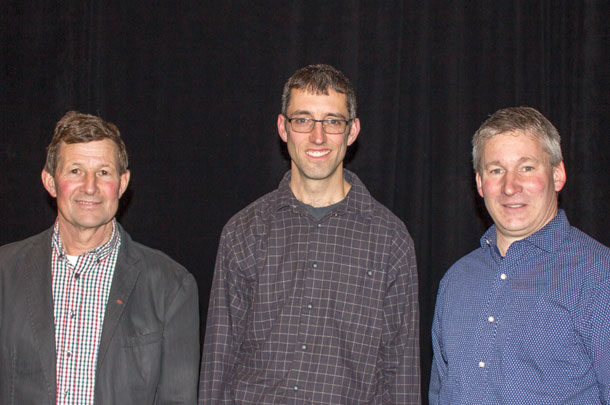

PHOTO: At the Western Canadian Dairy Seminar, three dairy producers that have achieved high Herd Management Scores discussed their management strategies. They included, left to right, Cees Haanstra, Chris McLaren and Dave Taylor. Photo by Karen Lee.

-

Karen Lee

- Editor

- Progressive Dairyman

- Email Karen Lee