With this increase in corn silage levels, we are also seeing high-moisture corn (HMC) and cobmeal becoming more and more common throughout Ontario, Quebec and the Maritimes.

Coupling increased corn silage inclusion rates with HMC or cobmeal has proven to be the foundation of economical rations on many dairies.

However, some dairymen have reported loose manure and erratic intakes among lactating cows fed long-stored corn silage and HMC with no readily apparent changes in nutrient content of the ration components.

Research results are now shedding light that digestibility changes, over time in storage, may be the underlying cause of these mysterious feeding problems. That perfect ration balanced in December or January may not be perfect any more, even though we are feeding what we think are the same fermented feeds.

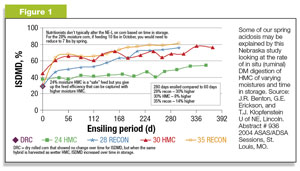

The beginnings of understanding this phenomenon was provided by University of Nebraska researchers, who conducted in situ dry matter digestibility (ISDMD) research comparing dry rolled corn with the same hybrid ensiled as HMC at moistures ranging from 24 to 35 percent.

ISDMD was conducted at 28-day intervals on samples out to at least 298 days in storage. Dry rolled corn and the lowest-moisture HMC (24 percent moisture) did not change significantly over time in storage, delivering a relatively stable digestibility profile, desired by many nutritionists.

However, all HMC treatments resulted in a higher ISDMD than the dry rolled grain, apparently as a result of the fermentation process. The largest changes in HMC ISDMD occurred during the first 28 days of ensiling, with linear changes post-28 days ensiled.

The rapid changes observed during the first month of storage supports the commonly endorsed recommendation of providing HMC (or corn silage) one to two months of fermentation before feeding.

However, what was not previously well documented was how the wetter HMC treatments continued to change in ISDMD for an entire year in storage.

Click here or on the image at right to view it at full size in a new window.

Results show ISDMD increased from day 60 to day 289 by 8 to 30 percent depending upon the kernel ensiling moisture (Figure 1).

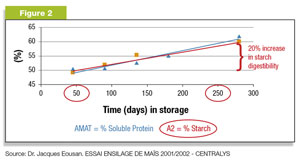

The research from Nebraska fits very well with some work done in France that showed an increase in starch digestibility of approximately 2 percent units per month in corn silage stored from 50 to 250 days.

When balancing rations, this 2-percent-units-per-month is a great guideline to use in terms of knowing how much HMC should be taken out of the ration over time to maintain the amount of starch seen by the cow’s rumen. (See Figure 2.)

Others reported research on changing starch digestibility in corn silages stored in bunker silos in the Netherlands.

The proportion of starch degraded after three-hour in situ incubations increased significantly with storage time with a mean of 53.2 percent at two months to 69 percent when stored for 10 months, or 1.975 percent per month.

The researchers concluded that the effect of time since ensiling on starch degradability should be considered in ration formulation.

Research findings are starting to put credence to field experiences suggesting starch and protein degradability increase over time in both high-moisture corn and corn silage.

However, the effect of fermentation should not be viewed as an acceptable alternative to adequate kernel damage from proper processing of high-moisture corn or corn silage. Using newly available starch digestibility laboratory methods or perhaps tracking water-soluble nitrogen levels may help nutritionists monitor these changes.

Ensiling higher-moisture corn grain (28 percent moisture and higher) can improve corn grain feeding value, but must be managed more carefully from both an ensiling and feeding perspective.

It may be helpful to collect and freeze samples that have fermented for 30 to 40 days to benchmark against samples fermented for a longer time (e.g. 200 days).

Understanding these changes can help nutritionists better formulate cost-effective rations, as well as prevent potential acidosis problems caused by longer-fermented feeds.

In summary, rapid changes in starch digestibility over the first month in storage certainly support the want by nutritionists and producers to have enough corn silage and high-moisture corn inventory that fresh feeding is not required.

In a perfect world, everyone would have 18 months’ worth of corn silage storage so that any corn silage fed would have been fermented for at least six months and would have already reached optimum starch digestibility, but we don’t live in a perfect world and this is certainly not always possible.

The same would be true for high-moisture corn, except a year in storage would be needed – even less feasible in the real world.

To get the most out of our corn silage and high-moisture corn, we still need to do the little things right. Harvest at the right time, process it as well as possible, pack it hard and use research-proven inoculants to ensure proper fermentation.

As we feed throughout the year, it is important to monitor cows as well as the ration, making sure that with the starch digestibility increasing over time we are not causing acidosis unknowingly by not making adjustments over time. PD

References omitted due to space but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.