Challenging growing conditions have created potential shortages in silage stocks over the past few years, which has sparked interest in putting up alternative silage crops, some more creative than others. It is important for producers to explore different crops as a way to produce more of their own cost-efficient feeds.

Understanding differences in strategies for growing, harvesting and ensiling alternative forage crops can help boost overall silage tonnage and inventories, ensuring sufficient quantities of high-quality, home-produced feed.

Warm-season grasses: Quick and high-yielding

Warm-season grasses are a quick, high-yielding alternative if the corn silage crop is compromised. Forage sorghums are high-yielding and can be a good substitute to corn silage, having similar protein content but maxing out at about 85% of the overall feeding value. Sorghums can be harvested as multi- or single-cut, and they should be ensiled at soft- to mid-dough stage (grain types) or between 32% and 37% dry matter (DM) (forage types). A single-cut system of non-heading types will need a killing frost before the harvest under conditions like those in the Midwest and planting at wider rows (15 inches to 30 inches) to help air flow for drying.

Sudangrasses are shorter and have thinner stalks than forage sorghum, so they can be wilted more easily and are harvested as early as 45 days after planting. Sorghum-sudangrasses are intermediates between sorghum and sudangrasses in terms of plant size and yield. Brown midrib (BMR) hybrids from these plants have been recommended instead of conventional hybrids because of the lower lignin content and higher digestibility.

These warm-season grasses have higher drought tolerance than corn, although drought stress may elevate nitrate levels in the plant. Proper ensiling can reduce nitrates by about 60%, but the production and release of toxic silo gases (NO, NO2) may increase as a side effect of this reduction in nitrates. Another way to decrease the amount of nitrates in the plant is to raise the cutting height, since they accumulate more heavily in the bottom portion of the plant. Also, if the crop was affected by frost, wait a few days before cutting to help reduce nitrate concentrations.

There is also a higher risk of accumulation of toxic prussic acid in sorghum and sudangrass plants, but it usually dissipates during wilting (or by waiting seven to 10 days after frost before harvesting).

Getting the plants to dry down sufficiently before ensiling may not always be possible, so using an inoculant proven to produce a strong homolactic fermentation to efficiently control and drive the fermentation is advisable. Excessive moisture in the forage mass stimulates overall microbial activity, which can prolong an inefficient fermentation without this control, leading to high digestible nutrient and DM losses.

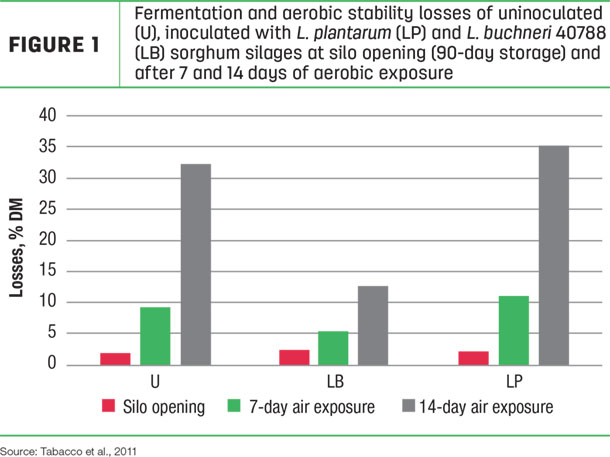

In situations where silage will be moved, crops were grown under stressed conditions, silage will be fed during warm months, or if there is a history of poor feedout stability, a dual-purpose inoculant containing Lactobacillus buchneri 40788 at full FDA-approved application rate is recommended (Figure 1).

The ideal length of cut for grasses depends on the moisture level, but the recommended range is from 3/8- to 1/2-inch, increasing to 1 inch for BMR hybrids. There is a wide range of options for these types of forage crops, so consider your local conditions and yield and nutritive value needs when making your choice.

Opportunities also lie in small grains and mixtures

Small-grain cereal crops, e.g., wheat, rye, barley, triticale, have gained popularity in recent years since large volumes of high-quality forages can be produced within short periods of time. Small grains can also be grown in a wide range of climates and soil conditions. However, they are cool-season grasses, so the yields will be lowered if grown over high temperature periods.

When used as double crop, small grains should be planted by early September and harvested in November. Oats and wheat mature more slowly than rye. Triticale has been a popular forage crop due to its yield, later maturity and also wide harvest window.

Small grains should be harvested at boot stage for best quality (15% to 20% CP, greater than 65% TDN), wilted to 32% to 38% DM for feeding to lactating cows and young heifers. These crops can also be direct cut and ensiled close to soft-dough stage (12% to 15% CP, 55% to 65% TDN) for other cow groups such as dry cows and greater-than-1-year-old heifers, according to UW researcher Matt Akins.

Particular attention should be paid during harvest because these grasses have hollow, air-filled stems and produce high volumes. Lower temperatures, cloudy or calm days (no wind) will impact the drying rate and quality of the plant, so wide swathing can be a good option. A shorter chop length is recommended, between 1/4- and 3/8-inch.

The risk of soil contamination during drying is high, which can pose more challenges during ensiling. The presence of soil will delay fermentation by resistance of pH drop, in addition to harboring many undesirable micro-organisms, e.g., clostridia. Inoculating these high-sugar-content crops with a dual-purpose inoculant as described above is recommended to ensure a high-quality end product.

Small-grain crops can be ensiled with annual legumes such as peas, producing a silage that should be more palatable and higher in quality than small-grain silage alone. Harvest timing should be based on maturity of the small-grain component since peas have less decrease in nutrient quality with time. Again, preferably, harvest when the small grain is in the boot to early heading stage.

According to retired Dan Undersander, professor emeritus, agronomy at UW, ensiling oats at the late boot stage results in the digestible fiber being between 60% and 70% NDF, giving in a relative forage quality (RFQ) of about 100. Adding peas (at a 3-to-1 stand ratio) will result in an RFQ of about 125 and will be more palatable in addition to having a higher nutrient composition.

Beans, beans … soybeans?

It may sound strange to ensile soybeans, but about a century ago at least 80% of soybean crop was used as hay, pasture and silage, based on good climatic adaptation and productivity on low-fertility soils.

Soybeans should be harvested at stages R3 and R4, when the pod is 3/16- to 3/4-inch long from one of the top nodes with a fully developed leaf, and chopped to a 3/8-inch theoretical length of cut for adequate packing. At this stage, the plant has high forage quality and digestibility, but wilting to 32% to 35% DM is necessary.

Soybean quality does not decline throughout the reproductive phase and so can also be harvested as late as when pods start to turn color and total yield is high (R7 stage); however, the high oil and protein concentrations at this maturity and low quantity of leaves make it more difficult to ensile, though there would be no need for wilting.

Similarly to other legume crops, the use of a homolactic inoculant is recommended considering the high resistance to the pH drop and slow fermentation, in addition to the high potential for suffering a clostridial fermentation when DM is low or sugars are limiting. An inoculant containing an enzyme blend to produce more soluble sugars may help overcome this limitation. Mixing soybeans with another forage crop that is more “ensilable” and palatable, such as corn or grasses, can facilitate fermentation and increase feed intake.

Corn stover – why not if it’s available?

In times of forage shortage, cornstalks can be used to stretch forage supplies in ruminant diets. Since there is low nutrient content and digestibility, corn stover has not really been considered for dairy cows; however, it could be an alternative for feeding to breeding heifers and dry cows, leaving more of the scarce silage for the milk herd.

It is recommended to process the corn stover through a tub grinder, rehydrate to about 50% DM and treat it with an alkaline solution based on calcium hydroxide to enhance digestibility before ensiling. Then, the mix should be stored for a 10- to 14-day period before feeding. Also, distillers grains can be added to corn stover to improve protein and energy profiles of the feed.

Key reminders for ensiling alternative crops

Overall, silage management for alternative crops follows the same key requirements we are all familiar with for traditional silage crops: maximum overall quality is dictated by what is harvested from the field, adequate plant moisture and enough sugars for fermentation are essential, rapid achievement of anaerobic conditions and the correct micro-organisms (specific lactic acid bacteria) to do the job (rapid pH drop and stability at feedout).

Keep in mind, you will get the best results by harvesting forage at the appropriate stage of maturity. It is also important to manage all aspects of ensiling:

- Use particle length recommendations.

- Treat the crop with a product proven to give the results you want (e.g., rapid fermentation, increased digestibility, stability at feedout).

- Pack tight with adequate tractor weight/time.

- Use the progressive wedge model.

- Cover as soon as possible, adding more weights over the seams and edges and allowing adequate overlaps (minimum 4 feet).

- Monitor and maintain the integrity of the plastic cover during storage.

These crops can produce very successful alternative silages by understanding their particular characteristics and adopting the appropriate management practices mentioned above. They can be great substitutes to traditional forage crops to help boost forage inventories and help you achieve your production needs and goals.