Based on the calculations using nutrition models, the smaller cow with greater milk production was the more efficient cow when selling at weaning. The smaller cow requires less feed for maintenance and greater milk production increases weaning weight, leading to the greatest biological efficiency. Although, there were some caveats to consider that were discussed in Part 1.

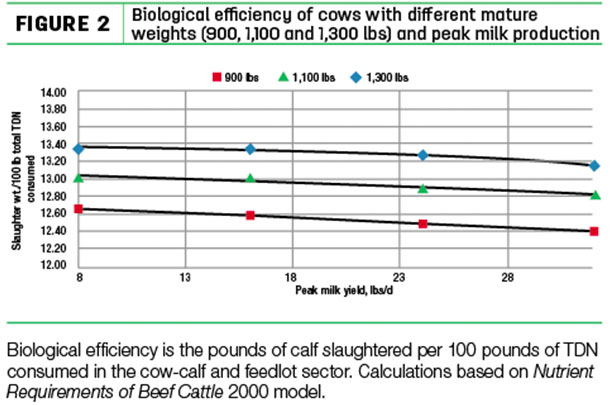

In Part 2 of this article, cow efficiency will be considered when calves are retained to slaughter. Figure 2 shows how cow mature size and milk production impact biological efficiency of the cow measured as pounds of calf slaughtered per 100 pounds of total digestible nutrients consumed in the cow-calf and feedlot sectors.

Interestingly, the results are opposite that seen when biological efficiency was evaluated at weaning. When calves are retained to slaughter, larger cows with lower milk production are more efficient. Biologically, it is more efficient to feed the calf directly than to feed the cow to produce milk for the calf. The inefficiency of nutrient utilization is compounded when nutrients go through the cow to be used by the calf.

Interestingly, the results are opposite that seen when biological efficiency was evaluated at weaning. When calves are retained to slaughter, larger cows with lower milk production are more efficient. Biologically, it is more efficient to feed the calf directly than to feed the cow to produce milk for the calf. The inefficiency of nutrient utilization is compounded when nutrients go through the cow to be used by the calf.

But as was stated in Part 1, biological efficiency is not equal to profit. It is more cost-effective to allow the cow to convert less expensive, grazed forage into milk for the calf than to feed the calf a more expensive feedlot diet.

That is, to the point where genetic potential for milk production exceeds the nutrients in the forage and supplemental feed required to maintain cow body condition.

Additionally, peak milk yield has minimal impact on biological efficiency when calves are retained to slaughter compared with calves sold at weaning. This is because the growth of the calf post-weaning greatly outweighs growth pre-weaning, where milk production has an impact on calf growth.

How big she gets

Cow size is also a factor influencing biological efficiency when calves are retained to slaughter. Large cow mature weight increases the pounds of calf slaughtered per 100 pounds of TDN consumed. This is due to what is referred to as the “dilution of maintenance” effect.

Large-frame calves grow faster such that a greater proportion of TDN consumed is used for growth rather than maintenance, resulting in greater efficiency. Larger cow mature weight produces faster-growing calves with greater slaughter weight, diluting the increased maintenance requirements of larger cows.

However, there can be consequences of cow mature weights that are too large. Cows with heavy mature weights produce steers with heavy and long carcasses that exceed the design capacity of many packing plants causing mechanical problems that slow down the production line.

Additionally, retail outlets have certain portion sizes served to customers and exceedingly large cuts of meat cause problems. Thus, cow mature weights can be so large that discounts are received for heavy carcasses when calves are slaughtered.

This analysis indicates that larger cow mature weight would increase biological efficiency of the beef production chain, and this is the current trend in the beef industry. Over the last 30 years, the beef industry has put a lot of emphasis on feedlot performance and carcass merit, indirectly increasing cow mature weight.

Research by Dr. Jude Capper at Washington State University indicates that reduction in beef’s environmental footprint, essentially a measure of efficiency, can be made by continuing to increase slaughter weight.

Increasing slaughter weight through genetically larger cows may increase biological efficiency of the whole beef production chain, but it hurts the bottom line of the cow-calf producer that sells calves at weaning.

Breeds and performance

Figure 2 shows very contrasting breeding goals to maximize efficiency when retaining ownership to slaughter compared with selling at weaning, shown in Figure 1.

(This was first published in Part 1.) When selling calves at weaning, breeding for smaller cow mature weight and greater milk production would maximize biological efficiency.

But when retaining ownership to slaughter, breeding for larger cow mature weight and lower milk production would maximize biological efficiency.

These contrasting breeding goals make it difficult for the cow-calf sector to maximize efficiency while maximizing efficiency of the beef production chain. Thus, two different biological types of cattle are needed to maximize biological efficiency in both the cow-calf and feedlot sectors.

Maximum efficiency could be achieved by breeding different types of cattle that excel in different traits rather than attempting to breed one type of cattle that is optimum in all traits.

Commercial producers need breeds or lines of cattle that produce efficient cows, which bulls from these lines can be used to produce replacement heifers. But also breeds or lines of cattle that produce calves with heavier slaughter weights, which bulls from these lines can be used as terminal sires to produce feeder calves.

With the use of sexed semen and artificial insemination, these two different types of bulls can be used in even the smallest herds to maximize biological efficiency in the cow-calf and feedlot sectors of the beef industry.

The idea of which type of cow is most efficient has been debated for many years. The answer depends on whether your end goal is selling a weaned calf or retaining ownership to slaughter.

Greater improvements in biological efficiency could be made by utilizing cattle bred to maximize efficiency for your particular scenario. And greater biological efficiency could be achieved in the beef production chain by breeding different types of cattle to develop replacement heifers versus feeder cattle. ![]()

PHOTO: Increased slaughter weight through larger cows boosts biological efficiency of the whole beef production chain, but can hurt the cow-calf producer that sells calves at weaning. Photo by Mike Dixon.

-

Phillip Lancaster

- Assistant Professor - Beef Cattle Production

- Missouri State University

- Email Phillip Lancaster