If you had read the analysis, you would appreciate the fact that the cotton industry used to burn and bury this waste product because the livestock and feed industries had the same notion as Dr. W.H. Jordan back in 1903.

In The Feeding of Animals book that he edited (p. 343), he stated that, “Such material as this [CSH] belongs with the very lowest grade of coarse fodder, as both composition and experience demonstrate.” This was said, even though research, albeit limited, during the late 1800s showed that CSH could be effectively used. However, the use of CSH sputtered along as research trials continued.

Fast forward to 1950 when Dr. F. B. Morrison stated in his Feeds and Feeding textbook, “When properly fed, CSH are generally about equal in value to fair-quality grass hay and are worth more per ton than corn stover, straw or poor hay. Hulls are well liked by cattle, even when fed as the only roughage.”

So why did it take so long for CSH to become adopted as a traditional roughage ingredient? Why were CSH not commercially approved until 1966 (Association of American Feed Control Officials – AAFCO)?

The answer is complex, but revolves around small profit margins and the livestock industry being skeptical of the effects that any novel ingredient has on cost per unit of product, animal health and edible animal products.

I am currently experiencing similar issues with a new ingredient that we created through my Texas A&M AgriLife Research Wood to Feed Program. The ingredient definition is Juniperus pinchotii and J. ashei trees (separate or in combination), which are chipped or ground and then hammer-milled (see Figure 1).

Value from the ground up

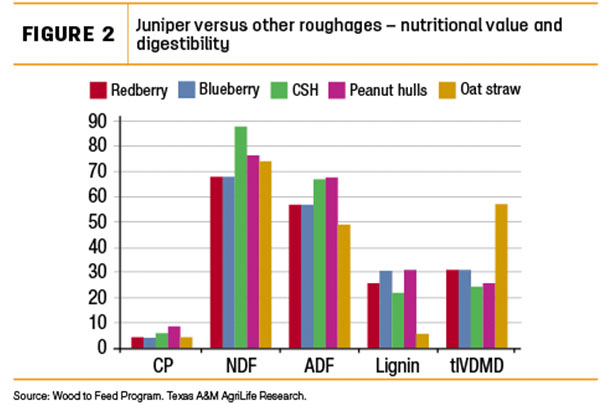

Nutrient and digestive characteristics of ground juniper are comparable to other low-quality roughage ingredients and at times, even better (see Figure 2).

However, the real beauty of this new ingredient is the fact that juniperus spp. trees are encroaching on rangelands and significantly reducing natural resources and land productivity. This is especially true in the Edwards Plateau area of Texas, where some juniper-infested areas have literally no grass production and significant surface water runoff.

Current management costs associated with removing or killing juniper trees is generally cost-prohibitive.

However, when juniper chips are valued at $20 to $30 per ton, this allows a landowner to recover the entire cost of juniper removal; approximately $300 to $500 per acre. Sounds great, but it gets better.

Ground juniper has unique characteristics not shared by any other feed ingredient in existence: (1) it requires no inputs by man to grow, e.g., land cultivation, planting, irrigated water, fertilizer, pesticides or herbicides; (2) when harvested, it can concurrently enhance natural resources and land value, increase forage production and water availability, and reduce the risk of wildfires; and (3) it is available year-round, thus not subjected to seasonal pricing characteristics or availability.

But wait; there’s more. Even though ground juniper is currently not an approved feed ingredient (working on it), the wood fiber industry in Texas is ready to start selling it year-round for $50 to $80 per ton (FOB); $50 when chips are given to the processor to create a final hammer-milled product.

The healthy alternative

Furthermore, ground juniper contains volatile oils (aka, terpenes, terpenoids) and condensed tannins (CT) at concentrations, which have been shown to positively affect animal growth performance, health and end product quality.

For instance, my lab has shown that terpenes or the ground juniper product can reduce internal parasite (Haemonchus contortus) motility by 44 percent and fecal egg shedding by 69 percent.

Additionally, we showed that incorporating 30 percent ground juniper in mixed diets can increase ivermectin efficacy by 66 percent in lambs. We have also shown that using ground juniper in mixed diets can reduce total feedlot costs (effectively replaced 33 percent of the ground alfalfa in a steer backgrounding diet), increase “healthy” meat fatty acids (e.g., conjugated linoleic acid; CLA), reduce saturated fatty acids and enhance carcass and sensory characteristics.

Additionally, we showed that incorporating 30 percent ground juniper in mixed diets can increase ivermectin efficacy by 66 percent in lambs. We have also shown that using ground juniper in mixed diets can reduce total feedlot costs (effectively replaced 33 percent of the ground alfalfa in a steer backgrounding diet), increase “healthy” meat fatty acids (e.g., conjugated linoleic acid; CLA), reduce saturated fatty acids and enhance carcass and sensory characteristics.

Results from our lab, which have shown beneficial effects of terpenes and CT in animal production systems, are not unique. Numerous other studies not only support our conclusions, but report additional benefits of feeding products that contain terpenes or CT. These studies will be used to support our future research efforts and hypotheses that ground juniper can be used to:

1. reduce urinary nitrogen excretion, fecal odors (associated with ammonia, skatole and indole) and fecal fly larvae development, all of which would be beneficial to feedyards;

2. increase bypass protein, which could reduce crude protein intake requirements;

3. reduce acidosis and bloat due to unique buoyancy and rate of hydration characteristics of the ground juniper fiber;

4. alter rumen microbial populations, acting in a similar manner as ionophores;

5. complement feedlot or pasture feed intake management systems;

6. enhance colostrum quality and milk fatty acid composition; and

7. maintain bodyweight and body condition during drought or winter conditions when used up to 50 percent of the mixed diet.

Mesquite and aspen

We have also successfully used two other ground juniperus spp. (J. monosperma, and J. virginiana) and ground Prosopis glandulosa (mesquite). That’s right, mesquite.

Sounds incredible and at times, unbelievable, until you consider that we are not feeding monogastric animals; we are feeding ruminal microbe populations.

In addition, the use of ground woody products as roughages is not only supported by our studies over the past 10 years, but by a 100-year history of using numerous woody plant varieties of sawmill sawdust, forestry slash and entire trees.

Much of this incredible history, along with numerous popular press articles showcasing livestock producers who used ground wood in their range supplements, is reported on the Texas A&M AgriLife Research Wood to Feed website – just Google it. In fact, numerous research trials led to a ground aspen definition being adopted by AAFCO in 1980.

Did you know that you can use ground aspen wood in your mixed diets right now? I bet you didn’t know that ground aspen is currently being used in beef cattle feedlot diets and feed mill pellets, albeit on a limited basis.

However, I believe that the limited use of aspen in livestock diets is about to rapidly change because unbeknownst to the aspen fiber industry in Wisconsin and Minnesota, until recently, a potentially huge market exists for them to sell a product they are already producing.

I’ll soon be headed northbound to visit with them about the nutritional and feeding value of ground aspen, helping them connect with animal science colleagues and helping them “talk the lingo” of livestock producers and feed manufacturers.

Even though many challenges remain to getting ground juniper commercially approved, all of us who have been involved in the Wood to Feed program are excited about the opportunities to reduce feed costs while concurrently enhancing natural resources.

At times, I feel like patting myself on the back for “stumbling” upon the known fact that ground wood can be used as a roughage ingredient. However, I am soon reminded by my dad that, “even a blind hog can find an acorn.” At times, he removes “blind hog” and replaces with “Aggie.” ![]()

PHOTOS: This series of photos shows the size of juniper trees and the terrain from which they were cut. Tough terrain increases harvesting costs and labor, as the author demonstrates in images on the right. Photos provided by Travis Whitney.

-

Travis Whitney

- Associate Professor

- Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center

- Email Travis Whitney