In 1898, five brothers left northwest Missouri and homesteaded in the Nebraska Sandhills. They were pioneering a land of good cattle range, open sky and new beginnings. Four generations later on the same homestead, their descendant, Dave Hamilton, is pioneering a new beginning in non-conventional ranch transitions.

Dave and Loretta Hamilton are well known in the Sandhills for exceptional range management. Dave can tell you the species of a dozen or more grass types growing on his range and what the palatability, growing features and nutritional characteristics are of each.

He’s had 45-plus years to learn this on an 18,000-acre spread (13,000 owned and 5,000 leased), with 1,200 cows on the ranch today. The range, with 17 inches of rainfall, hosts sand bluestem, indiangrass, switchgrass, prairie sand reed (50 to 60 percent), sand lovegrass and little bluestem – every grass is native.

Hamilton says, “Of the grass species, there’s one key species that I watch – sand bluestem. It’s the most desirable grass – it and indiangrass – because they’re the most palatable."

"I use those grasses and compare those to historical data on our range and use them to determine animal unit months (AUMs) – key species and then overall condition of pasture. Across the whole ranch, we’ll average 0.7 AUM per acre and that’s summer and winter grazing.”

The original herd of commercial Herefords incorporated Simmental about 35 years ago, using half-blood sires (Simmental/Angus – red and black) on half-blood females. He keeps about 15 to 20 percent of the heifers for replacements, using A.I. on these heifers focusing on birth expected progeny difference (EPD) and calving-ease sires.

Grass management

For 30 years, the Hamiltons have used planned rotational grazing using three grazing groups in a 10-pasture system. Sixty pastures average 320 acres in size, and cattle are moved every two to three weeks. In an average year, every pasture is grazed once during the growing season. After the calves are weaned and cows are preg tested, 70 percent of the pastures are grazed again during the dormant season.

This means the cows are essentially grazing 100 percent of the time for 11 months. The rotations are set so that during calving season, the cows can be moved into the pastures closer to the homeplace for about a month. During that time, they can be fed supplemental hay.

During Dave’s management, the acreage has expanded threefold, and the livestock has expanded by a factor of five. Part of the expansion can be credited to irrigation, with the establishment of two pivots that develop feed options.

The other expansion factor, Dave says, is due to rotational grazing, which increased carrying capacity by 25 percent. Dave says, “My dad started rotational grazing in 1962 with just two pastures, and slowly over time as we increased the number of pastures and increased the water supply – that’s the first limiting factor in any grazing system, is water – so as we increased the water supply, we’ve added fence. We didn’t just go from continuous grazing to a 10-pasture rotation overnight; it was gradual.”

Developing water sources for 60 pastures meant developing windmills – 60 of them, which will pump 8 to 10 gallons per minute with wind. During July and August when the windmills don’t pump enough, Hamilton uses 25 miles of pipeline with pressurized water (getting up to 35 gallons per minute).

And a third source of water on leased ground is provided through 4-inch submersible wells from 70 to 120 feet deep. When cattle are moved to the well-site pastures, Hamilton pulls a pump trailer with a propane generator to the well site and pumps water into 30-foot tanks.

Transition – now what?

It’s a beautiful, impressive spread made possible through pioneering efforts over many years. However, there is still one pioneering trail to trek – ranch transition. The Hamiltons have four daughters, who all have advanced degrees and are pursuing other career opportunities.

As soon as Dave and Loretta determined their daughters didn’t have an interest in ranching, they set a goal that if the right situation came along and the right people, they’d explore it, but as Hamilton says, “There’s some anxiety that goes along with it.”

“We made the decision to retain the land but lease it out,” Hamilton says. “Lon Larsen had worked for us for a short time (less than a year), but we’ve known him for about 21 years. He’s a native of Nevada and came to Nebraska and managed two other ranches here, and we just happened to cross trails about three years ago when he was looking for a change.

One thing led to another, until we leased the ranch to him.” But their leasing arrangement is perhaps not the common variety.

The uncommon lease

In 2015, Larsen and the Hamiltons worked out a three-tiered lease – one for the land, one for the equipment and one for the cattle. Hamilton says breaking out the leases creates more flexibility and stability at the same time.

At the end of each year, they sit down and go through each lease, making adjustments that are mutually agreed upon.

The leases also account for different land types and uses. Hamilton says, “In the land lease we have a separate rate for different classes of land. For example, we’ve got state-owned land at one price, which is extremely high – higher than private grazing land – a separate lease rate for deeded grazing land, a separate lease for wet meadows and a separate lease for irrigated land.

So you can manage any one of those parts separately. But we negotiated all those things in the beginning and then at the end of each year, we’ll take a look at it again.”

The ranch encompasses a wet valley on the north end that will produce one-and-a-half to two times what the native range produces and is valued at a higher rate. Those areas are cut for hay and then the regrowth is grazed in winter. The pivot-irrigated ground is also valued at a higher rate because of the tonnage and feed options it presents.

The equipment lease contains a threshold price on parts and repairs, as Dave retains ownership. Anything under that price is Lon’s responsibility; anything over that price is Dave’s responsibility.

The livestock are leased on a share basis. Hamilton and Larsen set up a budget; the portion of the budget Larsen pays for is the portion of the revenue he receives from the calf crop.

After compiling their budgets, it worked out to an 80/20 ratio, with Larsen responsible for 80 percent of the expense on the cowherd and receiving 80 percent of the revenue.

Crucial to both parties in the arrangement was grass management. Larsen says, “One of the unique things about our situation is that Dave and I are so close in philosophy – if you take care of the land, then the land will take care of you.”

Where rubber meets the road

It all looks good on paper, but what happened when the leases were implemented – “where the rubber meets the road?” Despite the similarity in management philosophies, changing management hasn’t been without its bumps. Larsen says, “When management changes, things happen. It’s the first time for me in my management system I haven’t been able to maintain or increase the production of a ranch when I came in and took over an operation.”

Click here or on the image above to view it at full size in a new window.

Was it hard for Hamilton to let go of everyday involvement in the ranch? “Yeah,” he says, “certain parts of it. When we first made the decision to lease it, we wanted to find someone who would manage it in a similar way that my wife and I did."

"And we found that couple – but yeah, once you’ve managed it for 40 years there are certain parts of it you really miss. But to be fair to them, we don’t want to look over their shoulders. We want them to do it their way. There are certain parts – like checking 2-year-olds in the middle of a night in a blizzard – that you don’t miss.”

Larsen doesn’t take this opportunity lightly. He says, “Dave and Loretta really created an opportunity for me. It’s a dream – it’s a dream come true for both Dana and me. I can’t say enough about that opportunity.” And both Larsen and Hamilton seem pleased with the arrangement.

And the Nebraska pioneering spirit lives on. ![]()

See more of the operation in this slideshow.

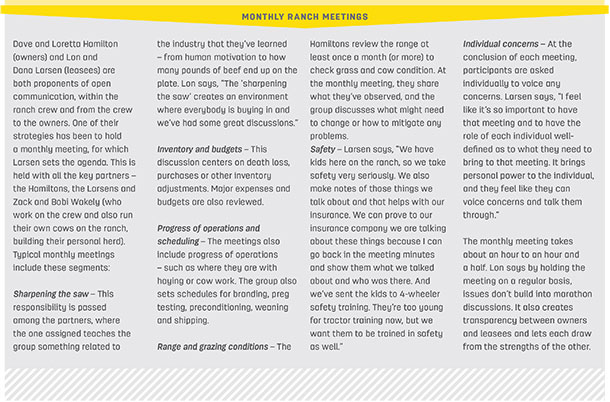

PHOTO: The Hamiltons now lease the ranch to Lon Larsen and communication is paramount to ongoing success. Hamilton regularly discusses range conditions with Larsen and his employee Zach Wakley (seated in the pickup). Photo by Lynn Jaynes.

-

Lynn Jaynes

- Editor

- Progressive Dairyman

- Email Lynn Jaynes