Certainly among these are breed composition and the contribution the bull may provide to direct or maternal heterosis, as well as a variety of growth, maternal and carcass traits. Perhaps among the most important is calving ease.

In the case of replacement heifers, we need to think of calving ease as both a trait of a calf (how easy it is born, or direct calving ease) as well as a trait of the cow (how easy the cow gives birth, or maternal calving ease).

There is a genetic component to both the direct and maternal aspects of the calving ease trait. As such, producers should be aware of when to use which measure to aid in the production of high-quality replacement females with the expectation of long productive lives as well as to minimize dystocia in first-calf heifers.

Before we discuss the two different calving ease EPDs, a brief discussion on why producers should use calving ease EPDs rather than birthweight EPDs to control dystocia rates in heifers and cows.

For cow-calf producers, calving ease is the economically relevant trait associated with dystocia. Economically relevant traits (ERTs) are those that directly generate revenue or incur costs in beef production systems.

For a commercial cow-calf producer, dystocia (or lack of “calving ease”) is what generates costs in a cow herd through direct losses of calves and their dams, increased labor costs and certainly lower reproductive rates among cows that have experienced dystocia.

Birthweight is an indicator trait. In this case, birthweight provides some information on calving ease. Birthweight alone doesn’t directly generate revenue or incur costs independent of calving ease.

It’s important to recognize that there is an optimal range of birthweights in beef cattle. Certainly, too heavy of a calf is a problem during delivery of the calf – hence our selection, at least historically, for lower birthweights.

However, too small of a calf at birth is problematic as well. This is especially true for winter-calving or spring-calving herds.

During severe cold stress, low-bodyweight calves are more susceptible to hypothermia and subsequent death or disease issues.

Indeed, very low-birthweight calves in northern latitudes can have dramatically reduced survivability when born in winter months.

Birthweight only accounts for 55 to 60 percent of the genetic variation in calving ease. So selection for reduced birthweight alone won’t improve calving ease as much as selecting directly on calving ease.

And since birthweight is strongly correlated with other growth traits, reduction in birthweight is usually associated with decreased growth performance at weaning and yearling.

When selecting a service sire for use on virgin heifers, it is recommended to focus on selection of bulls with calving ease EPDs in the top 20 percent of the breed being considered or better.

If you are using A.I., select bulls with high-accuracy calving ease EPDs to further minimize risk of dystocia events.

We’ll start our discussion on the use of maternal calving ease (MCE) EPD and its use in selection of bulls to produce replacement heifers. MCE EPD describes the difference in the expected rate of dystocia among sire groups of daughters.

For instance, if Bull A has a MCE EPD of +10 and Bull B has a MCE EPD of -2, we’d expect Bull A’s daughters to have 12 percent more unassisted calvings (i.e., fewer dystocia events) compared to daughters of Bull B when these daughters are mated to service sires of similar genetic merit for calving ease and birthweight.

Remember, MCE is calving ease viewed as the ability of a sire’s daughters to calve unassisted. Typically, MCE has a negative genetic association with calving ease (direct) and a positive genetic relationship with growth and mature size.

So it’s important producers don’t just select for higher levels of calving ease in their herd, as that will have a tendency to decrease the maternal calving ease genetic potential in the cow herd.

Once a producer has used MCE in the selection of sires to produce replacement heifers, one should transition the selection focus to identification of high calving ease EPD sires to be mated to virgin heifers to produce their first calf.

In this scenario, selection for high calving ease EPD helps increase the percentage of calves born without assistance to first-calf heifers.

In this case if Bull C has a calving ease EPD of +12 and Bull D has a calving ease EPD of +2, we’d expect Bull C’s calves to have 10 percent more unassisted births.

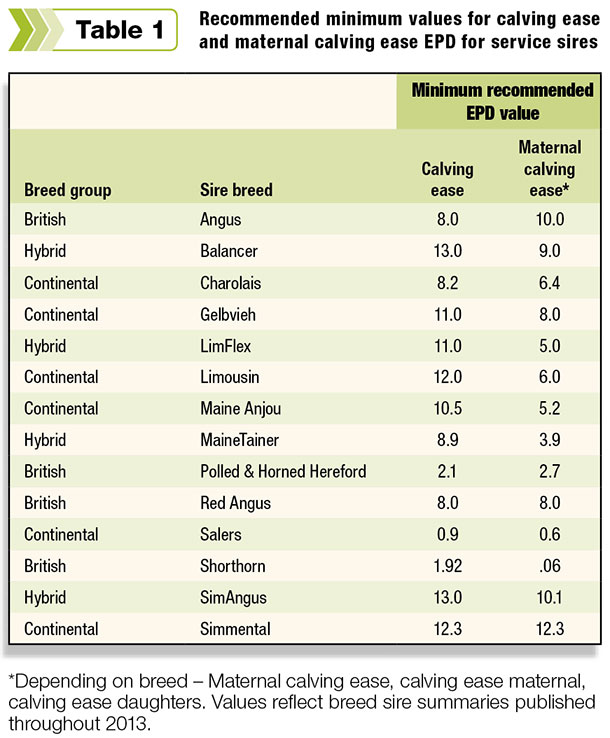

Recommendations for MCE EPD minimums for sires to be used to produce replacement heifers and calving ease EPD minimums for heifer service sires are in Table 1.

Regardless of breed group (British, Continental or Hybrid), the MCE recommendation reflects the upper 25th percentile of active sires.

Percentile requirements for calving ease EPD vary with breed groups: Continental upper 15 percent, Hybrid upper 20 percent and British upper 30 percent.

Producers may adjust this recommendation up or down based on individual needs that reflect herd-based experience in dystocia rates in first-calf heifers.

Combining the use of calving ease and MCE EPDs in your selection system will help assure a successful calving season and decreased dystocia in your first-calf heifers.

Dystocia in heifers due to poor selection decisions can be a very expensive mistake resulting in lost profits due to cow and calf death loss, extended postpartum intervals and poorer conception rates in re-breeding first-calf heifers.

Be sure to do your part this spring when selecting bulls or semen for building and breeding replacement heifers. ![]()

—Excerpts from Kansas State University Research and Extension newsletter Beef Tips, January 2014

Bob Weaber

Extension Beef Specialist

Kansas State University