Real disposable personal income decreased 4 percent in January, in contrast to an increase of 2.7 percent in December.

In dollars adjusted for inflation, personal income has been flat since the 2009 recession began. This has kept consumers cautious as they feel the lack of spending power when they fuel up the car or look over the meat case at the grocery store.

With sequester a reality and budget battles in the nation’s capital an ongoing saga, the longer-term impacts on the economy and livestock industry will remain to be seen.

On the brighter side, U.S. consumer beef demand, after slumping from 2007 through 2009, began to climb up again in 2012. Consumers are enjoying beef – more at home instead of dining out.

This has led to more use of less-expensive cuts, and slow movement of middle meats. Due to tight supplies of beef, per-capita consumption is decreasing. 2013 supplies will be about 55 pounds per person. The average from the late 1980s until 2008 was about 65 pounds.

International trade

The U.S. exports high-value cuts and imports lower-value cuts mostly for grinding or processing product. On a volume basis, our imports have usually been higher than our exports.

Because of the difference in type and quality, on a dollar-value basis, exports have usually exceeded imports. Net imports (all exports minus all imports) from the 1990s to 2004 averaged between 1 and 3 percent of U.S. production.

When the BSE cow was found in late 2003, most countries cut off our exports, but that ground has been regained.

For 2010-2012, net imports were negative, meaning we exported more pounds than we imported. In 2012, imports increased while beef export tonnage declined year-on-year.

One factor in the increasing imports was that U.S. production of lean finely textured beef, known to the media as “pink slime,” was essentially stopped in 2012. This gap in availability of a very lean product is being replaced by imports.

Another factor has been the very small beef herd, which limits the supply of cull animals.

Another factor has been the very small beef herd, which limits the supply of cull animals.

Northern Mexico has been subject to the same drought conditions as Texas and the southern states in 2011-2012. As a result, cattlemen there have been forced to reduce or sell off herds and move calves to the U.S. to find feed.

This has pushed imports of feeder cattle above the average in both years. Unless moisture finds its way to pastures, that movement will continue.

However, the Mexican breeding herd has shrunk dramatically, so it’s likely U.S. cattle imports from that country will drop significantly in 2013.

Drought – a game-changer

In 2011, the drought was very severe but concentrated mainly in the Texas – Oklahoma area and southern Georgia. In 2012, the drought was very widespread with nearly two-thirds of the country rated between severe and exceptional.

The Corn Belt was hit hard with low yields and uneven quality. The area of drought has been receding and the eastern Corn Belt is at normal conditions.

Although the western Corn Belt and central-northern Great Plains area is still affected, recent storms have improved the moisture situation there.

This year is a pivotal year for U.S. livestock producers, and the most important driver will be Mother Nature. First, the size of the corn crop will be critical.

Current forecasts are for more normal moisture conditions which would, if a reality, bring in a larger corn crop in 2013 and push corn prices into the $5-per-bushel region.

But there are considerable unknowns about what will materialize. Pasture and range conditions also will be a driver of cattle prices in 2013.

Markets and outlook

Markets and outlook

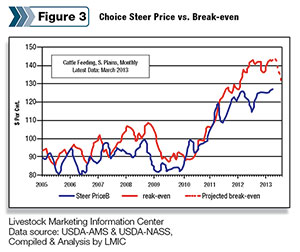

With that background, let’s take a look at the potential for the cattle markets in the next few months. The cost of feed is key to industry profitability.

There are some things driving the current high levels of prices for cattle, and we’ll examine those and look at the probable price situation.

Feedstuffs are key

The cost of feed, both grains and forages, has risen considerably since 2006. Corn is the largest crop, and as such, influences the other feed grains.

The drought of 2012 cut supplies and carry-over stocks, which put a high floor under prices. Recent improvement for moisture has lowered corn prices, but the 2013 crop could remain subject to weather this summer.

Hay stocks on Dec. 1 were the lowest since 1974. The combination of reduced hay production and increased hay feeding due to drought the past two years leaves the U.S. with severely depleted forage supplies.

Total U.S. Dec. 1 hay stocks were 76.5 million tons, the lowest Dec. 1 stock level in data back to 1974. This stock level is down 25.5 percent from the 2006-2010 five-year average.

The reduction is severe in many states. Pasture conditions in most regions are similarly poor. With the final pasture and range condition report at the end of October, 15 states had more than 60 percent of pastures in poor or very poor condition, and another five states had 40-60 percent poor to very poor pasture conditions.

Anecdotal indications are that crop aftermath, especially corn stalks, have been heavily used this winter to provide critical feed resources for cattle.

Cattle market drivers

In a past beef advertising campaign, the question was famously asked, “Where’s the beef?” We may be asking that in a different light with a total cattle herd of 89.3 million head, the lowest since 1952.

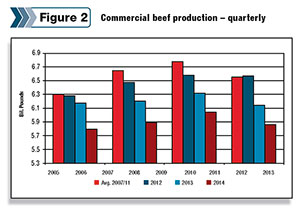

The incredibly tight supply of beef has and will support prices until herd numbers rebuild, a situation likely to take at least three years and possibly more.

While price incentives for rebuilding have been in place since 2010, drought and high prices for crops coupled with uncertainty about markets have kept the U.S. beef cow herd on a downward trend.

While price incentives for rebuilding have been in place since 2010, drought and high prices for crops coupled with uncertainty about markets have kept the U.S. beef cow herd on a downward trend.

Click here or on the image at right to view it at full size in a new window.

However, the picture is more uneven on a state level. The northern tier of states has increased numbers while most central and southern states have cut herds.

If normal moisture returns to the plains and western Corn Belt – a big if at this point – 2013 may mark the turnaround year for herd numbers.

In the Jan. 1 inventory report, cattlemen reported plans to increase heifer retention by nearly 2 percent. Additional spring moisture is the key to more grass and hay.

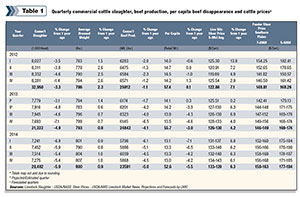

At current grain prices, feedlots are struggling to cover operating costs. Packers face similar narrow margins. Those conditions will limit how much feedlots are willing to pay for placements.

With normal moisture and a return to lower grain and forage prices, feeders could return to a positive margin situation and support more strength in feeder prices.

Another factor in the equation is consumer willingness to pay. The CPI for meats went from 215 to 230 in 2011, a 7 percent increase.

In 2012 it went up slightly more to 233, an 8.4 percent increase since 2011. With consumer disposable income flat, these price changes are noticed on every trip to the supermarket.

Although demand has improved since 2009, prices could reach levels that cause consumers to switch to lower-priced alternatives.

Cattle prices and profitability

Whether more drought leads to more herd reduction or more moisture leads to more heifer retention, the availability of beef will be very tight over the next two to three years.

With a larger corn and grains supply going forward as well as improved pasture, range and hay conditions, herd rebuilding will support high prices.

With that, we’ll see per-capita supplies drop to historic low levels of between 50 to 54 pounds. 2010 was the first time since 1958 that per-capita consumption was below 60 pounds.

Managing in this economic environment

We will continue to experience market volatility and possible unknown impacts to the market. Continued decline in beef availability is a certainty for at least two years until herd rebuilding can begin to provide more production.

Even with increased corn production and improved prices, corn is likely to remain near $5 to $6 per bushel.

For the cow-calf operator, even with high prices and solid profits, caution and continued good management is advised.

Mistakes will be costly. Where possible, reduce or pay off debt, accumulate a reserve and refine your production management. With the high cost for feed, placements of heavier calves are more desirable when available.

The cheapest way to put gain on is with grass. Grazing management will continue to be a critical management focus for the foreseeable future.

Non-traditional methods may also be used. In southern Idaho, for example, started dairy bull calves are selling for as much or more than their heifer mates.

With supplies of feeder calves tight, these calves are another option for feed yards to keep the pens from being empty. ![]()

James Robb is the Director of the Livestock Marketing Information Center, Denver

Wilson Gray

Extension Economist

University of Idaho