I know, Will Rogers said it many years ago, “Personally, I have always felt that the best doctor in the world is the veterinarian.

He can’t ask his patients what is the matter … he’s just got to know.” Well, there is some truth in that, but times have changed and making a correct diagnosis over the phone creates an additional hurdle.

By the way, where is Will Rogers when the nation needs him? This is a question for another day, perhaps.

With the relative shortage of cattle veterinarians, this topic deserves some space. Let’s discuss some of the information a rancher can gather to help their cattle and their veterinarian.

Good decisions are made based on good information and the best decisions are based on the best information. What do you need to tell your veterinarian besides, “She ain’t doing right”?

In medicine we usually start with what we refer to as the signalment – this is the animal’s age, sex and breed and usually includes some type of ID.

So, as an example, you may call about a 7-year-old Angus cow (supposed to be five months pregnant) and ear tag number 524. That’s the basic information or signalment. Then other helpful information will be added to this foundation.

When I examine a cow I do what is called a physical exam – this term stems from the fact I use my physical senses: sight, touch, hearing and smell – to examine the animal.

As an experienced cattle producer you do the same, often without knowing it; it’s just common sense. The basis of the physical examination is temperature, pulse and respiratory rate (often referred to as TPR).

Therefore, you will need some very basic equipment and some training from your veterinarian. The equipment you will need is a large animal thermometer and a workable stethoscope.

You can obtain both from your veterinarian and he or she can give you good advice on how to use and care for these items.

If you use an “old-fashioned” rectal thermometer with mercury, I recommend you tie a six-inch to eight-inch piece of string through the hole at the end of the thermometer and to an alligator clip, such as those used in electrical testing.

You can drill the end of the plastic case for the thermometer so the string will pass through. This allows you to put the thermometer back into the plastic case once you are done and have cleaned the thermometer.

The thermometer is placed in the rectum of the animal and the alligator clip is attached firmly to the tailhead hairs, so when the animal defecates the thermometer will not end up in the bottom of the chute under three pounds of fresh feces, but will be hanging from the tailhead and can be re-inserted.

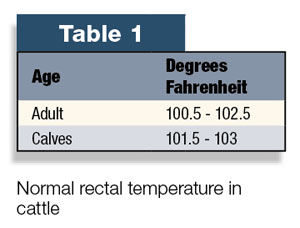

The normal rectal temperature for cattle and calves is listed in Table 1. Alternatively, there are electronic thermometers available; however, they tend to be more expensive, have greater maintenance requirements and often “disappear.”

No matter which type you use, clean it with water and soap or disinfectant when you finish before you store it.

The second piece of equipment is a stethoscope. Be sure to work with your veterinarian to pick out the one that will work for you – one that is well made, reasonably priced and durable.

The stethoscope can be used to listen to the heart and determine the pulse rate (beats per minute), listen to the lungs for abnormal sounds and determine the respiratory rate (breaths per minute) and listen to the rumen to determine if the animal is ruminating normally.

The normal pulse for cattle and calves is listed in Table 2 and the normal respiratory rate is in Table 3.

Cattle over 5 to 6 months old are usually ruminating actively and, by placing the stethoscope high in the left flank (behind the ribs and below the bones of the spine there is a triangle without bones called the paralumbar fossa) and listening quietly, you should be able to hear one to two strong rumen contractions per minute.

For all uses of the stethoscope get some training from your veterinarian – you should count on an hour or two, at a minimum, to examine several animals to get the hang of the technique and to understand what “normal” sounds like.

Other observations you should make as a routine are:

- Nasal discharge – clear, cloudy, white, thick, blood-tinged

- Signs of abnormal appearance of the nose, eyes or mouth

- Mucous membrane color – inside of mouth, white part of the eye or inside of the vulva; here you are looking for a normal light pink coloration – abnormal findings are white (pale, anemic) or yellow (jaundice)

- Character of the feces – diarrhea, constipation (fecal balls like horses), any mucous or blood mixed with feces

- Any signs of lameness, weakness or inability to walk normally

- Any abnormal odors to the animal

- The color of the urine – in black cattle the color of the mucous membranes can be difficult to assess, as their mouths and the area around their eyes are often black and in these cases the inside of the vulva is a good place to observe for the normal pink color.

Another observation you can make relates to the animal’s state of hydration or dehydration. This is particularly important for calves with diarrhea.

For calves that are scouring or reluctant to stand, pull up on the skin along their neck – in a normal calf this “tented” skin will “snap” back into place within a second or so. If the skin takes five to 10 seconds to return to its position, the calf is 6 to 8 percent dehydrated and needs oral fluids (two to four quarts) immediately.

If the skin takes 11 to 15 seconds, the calf is 9 to 10 percent dehydrated, in danger of dying and will probably need intravenous fluids shortly to prevent death. Your veterinarian can educate you regarding other aspects of assessing hydration status in your animals.

With these simple tools, some training and a good working relationship with your veterinarian, you are now ready to make a phone call that will help your animal, your veterinarian and your bottom line.

Now that phone call may sound more like this, “Doc, I have a 4-year-old, black-white faced cow (#847) with a 104-degree temperature, pulse of 85 per minute, respiratory rate of 42 per minute, lungs sound clear but harsh and there is a bad smell coming from her rear end.

Also, she appears to have some diarrhea with a little bright blood in it and she seems to be straining a little.” Now this is real information that can help everyone make an informed decision.

This article is not meant to be a “Do It Yourself Guide” but is meant to stimulate producers to consult with their veterinarians, get some additional training (and a little equipment) and learn to gather some information on their animals when they become ill and need your help.

The most important message is to get some advanced training from your veterinarian so your conversations can go beyond, “Doc, she ain’t doing right.” It’s like Casey Stengel once said, “It’s amazing what you can observe by just watching.” ![]()

This originally appeared in the California Cattlemen’s Magazine.

Extension Veterinarian

University of California, Davis