But Capper added there are still opportunities producers should seize upon to make their operations more sustainable with land, water and other resources.

“As a beef industry, we have a huge opportunity to cut our total carbon output by improving efficiency of the farm,” she said. “All of the things we do between calves being born and then going to slaughter make a huge difference overall to carbon, land, water and energy and so on.”

Capper, a faculty member at Washington State University’s Department of Animal Science, shared some of her innovative research on the environmental impact of beef production as it related to sustainability and the ILC’s theme “Beef’s Greatest Challenge: Feeding the World.”

Producers are frequently under a barrage of criticism from animal activists and environmentalists for the amount of water, feed and land that goes into beef production. But Capper said such data are regularly presented inaccurately, unfairly or in a false context, and mostly to consumers who know little about ag production.

As an example she cited the false claim that one pound of beef requires 2,463 gallons of water.

“These agencies understand that numbers have power,” she said of statistics cited by PETA, The Humane Society of the U.S., and other environmental groups. “Whether the numbers are true or not doesn’t matter. If it’s out there as a number, it will get publicized all over the place.”

The demand for more animal protein will help producers plan ahead as the world population heads toward 9 billion people.

“Over that time we’ve got to do essentially what the beef industry does best: We need to improve productivity and to improve efficiency.”

Enhanced growth rates

To see how efficiently beef production uses its resources, cattle ranchers should compare trends between 1977 and 2007, Capper explained.

For starters, there’s the increase in carcass weights. Three decades ago, it took five head of cattle to produce the amount of beef we get from four head of cattle today.

Whereas cattle in 1977 required 606 days to grow from birth to slaughter, that growth period dropped to 482 days in 2007. “So we’re saving 124 days of land, water, waste and feed,” Capper said.

Multiplied for five animals in 1977, that’s 3,030 days of animal production. In 2007, for four animals it was 1,928 days of production.

“We saved 1,100 days of resources and carbon by improving growth rates and yield per animals,” she said.

Improving all stages

Capper said it’s common for beef production to focus heavily on animals in the feedlot to improve sustainability. But in reality, all stages of production need to review efficiencies.

Again, comparing 1977 to 2007, Capper said the industry uses just 81 percent of the feed required for production three decades ago, 88 percent of the water, and has reduced manure and methane production to 82 percent of 1977 levels.

Meanwhile, by using fewer animals the total carbon footprint per pound of beef has come down by 16 percent, Capper said. “That’s a huge achievement that everyone should be proud of. It’s not done by installing digesters, or methane vaccines, or any of these other things, but by doing what the beef industry does best: Improving productivity and efficiency to move beef in an affordable, positive manner, and to improve future sustainability.”

Traditional beef and niche beef

The growth of natural, organic and grass-fed beef systems as a whole is good for the industry, Capper said, because they provide consumers choices they want at the dinner table. “There’s a place for every single system if it’s environmentally responsible, socially acceptable and economically acceptable,” she said.

“I am not anti-grass-fed beef,” she said. “What I am anti is mismarketing and playing to the fears of the consumer.” Producers need to point out the science disproving the nutritional claims saying grass-fed beef is better than conventional beef.

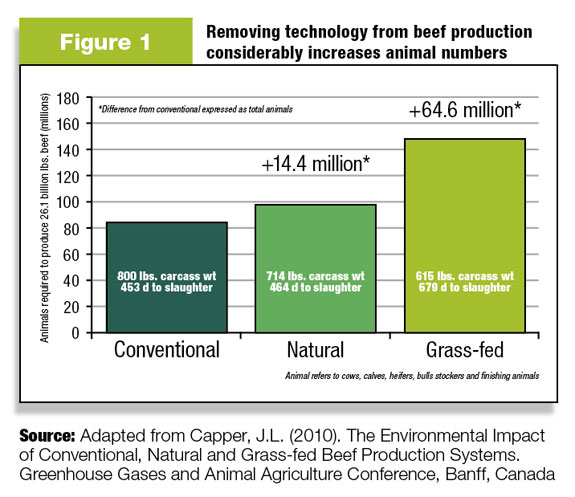

To illustrate, Capper pointed out not only the difference in carcass weights between all three systems, but also the days required for the cattle to finish. (See Figure 1).

If all beef production were to adapt grass-fed beef models, Capper said, the acreage of land required would increase by 131 million areas. Greenhouse gas would also jump by 134.5 million tons a year; and water usage would jump by 468 billion gallons a year.

Meatless Mondays

Capper noted the growing popularity in schools and government programs to remove meat protein from menus. Meatless Monday advocates cite a Carnegie-Mellon study claiming that going meatless for one day a week saves more greenhouse gas than shifting to a local food source diet.

But that claim lacks a control group with a truly locally produced diet, making any comparison incomplete.

Capper said with a U.S. population of 330 million people, and using EPA data, that red meat and dairy account for 3.05 percent of total carbon emissions on an annual basis. If they all went meatless every Monday, every week for a year, “that would cut total greenhouse gas emissions by 0.44 percent – or 1/200th of our total carbon.

“I’m not saying we shouldn’t totally cut our total carbon emissions,” Capper said. “But to think we can make this huge difference by not having red meat and dairy, frankly just doesn’t make sense.”

Rebutting falsehoods

Water resources are a particular issue said Capper, given the precious resource that it is and the inclination environmental groups have for distorting figures of water use in beef production.

Capper looked particularly close at a National Geographic story from April 2010 showing how much water is used in everyday life, for good such as apples, bread and chicken. The article cited data from Water Footprint Network to claim that 1 pound of beef required 1,799 gallons of water.

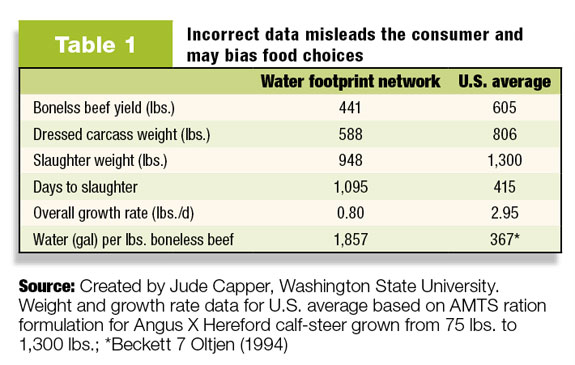

But on closer examination, Capper said the Water Footprint Network data contained several inaccuracies, including a line stating “in an average industrial beef production system, it takes an average of three years before the animal is slaughtered to produce about 200 kg of boneless beef.”

For starters, the assumption that an industrial beef producer would feed animals for three years “is just insane,” Capper said. Most animals in a conventional system are ready for finishing by 14 to 15 months.

As for the amount of beef produced, Capper said 200 kilos is about 440 pounds of beef from a carcass. The numbers were flawed both on the inputs and the final outputs of beef, so she did her own comparisons (See Table 1).

The Water Footprint Network’s data showed low carcass weights, longer days on feed, and lower rates of gain, than what traditional beef producers repeatedly perform at, Capper said.

And as for the claim that it took about 1,799 gallons of water for a pound of beef, Capper said her research showed it was closer to 367 gallons of water per pound of beef.

The difference of course is that the lower numbers appeared in the Journal of Animal Science, read by the beef industry and downloaded by a few hundred people, while WFN’s questioned data appeared in National Geographic, an international publication read by millions.

Needs for efficiency, productivity

Even with the progress made, Capper said, beef producers have room to improve their methods of sustainability and reduce environmental impact. Examples she provided included:

- Reducing time to reach target weights – Faster growth rate, feed efficiency, optimizing diet formulation and proper use of beef performance technology are all key steps.

- Minimize losses within the system – Protect herd health by reducing morbidity, mortality and parasite infection.

- Improve reproduction efficiency – Only 89 percent of cows have and wean a calf per year. That’s good compared to other nations (Brazil has averages of 6 percent), but the U.S. can improve even more.

- Boost land carrying capacity – Maximizing the healthy use of arable land will require improved pastures and forage varieties.

- Reduce post-harvest resource use and emissions, such as water, paper, plastics and Styrofoam.

PHOTO:

Dr. Jude Capper of Washington State University told International Livestock Congress attendees that anti-agriculture forces will use numerical data to prove their philosophy, even when the figures are overblown and distorted.