Management-intensive grazing refers to a grazing system where animals are allowed to graze only a small portion of the pasture while other paddocks are rested and allowed to recover. Grazing annual cover crops using management-intensive grazing is a great way to add an additional rotation crop and produce income for the farm.

Species of cover crops planted, class of cattle and accessibility to fencing and water should all be considered before adding cover crops as an annual forage crop.

Picking your cover crop mix for cattle grazing

There are dozens of plant species, both cool- and warm-season types, which you could include in your cover crop mix. However, before you choose what to put into your mix, think about your growing season, water availability and the class of livestock that will be grazing.

When considering growing season, know when the last and first freezing days typically take place. This will help you choose what cool-season or warm-season species you can use in your environment.

In a recent Western Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) project, a producer was looking at the use of cover crops as a forage source for stocker cattle from June to October. To accomplish this, a 148-acre pivot was seeded using a no-till drill to plant a cool-season mix of forage barley, forage oats, forage peas, common vetch and purple-top turnip (Table 1) the second week of May.

All the species in the mix grew successfully; however, not all had the same regrowth and forage potential. The oats and barley in the mix grew quickly and provided feed early. Once grazed, both the oat and barley showed regrowth potential by producing additional tillers, but oat was more productive in regrowth. As the longer days of summer came on, the barley headed and more or less finished.

The oats headed but continued to produce new tillers as well. The peas and vetch responded well to grazing when grazed early. The peas were available earlier on while the vetch, a perennial legume, took time to germinate and grow. The turnips grew quickly, providing greens and tubers, which were excellent feed, especially as the cattle learned to eat them.

Following the first grazing of the cool-season mix, the producer planted a warm-season mix to add additional late-summer forage and to provide high-quality fall grazing. The mix was no-tilled into the grazed paddocks starting July 1 (Table 2).

We determined the warm-season mix was not as effective because it was not able to compete with the residue and regrowth from the cool-season mix (Figure 1).

Also, as the oats and barley headed out, seeds were dropped, which sprouted and provided adequate fall forage.

Choosing your cattle and when to use them

The next consideration is when to put cattle in and how many. In a management-intensive grazing setting, it is common practice to move cattle at least once, sometimes twice a day to achieve the target grazing goals. Class of cattle can make an impact on this, as cows are typically less selective grazers and will graze more uniformly.

However, cows do not have as high of a potential for gain and will not be as profitable as stockers that are in a higher conversion state. This is especially true if the grazing is being paid per pound of gain. Simply put, this system will work with any class of livestock but is more profitable with growing cattle. In the Western SARE project, 45 days after seeding, cattle were put into the first grazing paddock.

Paddocks used in this management-intensive setting were approximately 1 to 3 acres in size and contained 200 head of 600-pound spayed heifers. The pasture manager realized after a few days the forage was getting ahead of them and decided to increase paddock size to 6 to 8 acres per day to allow the heifers to graze off the top of the plants to keep the field in relatively the same growing phase.

In a management-intensive system like this one, or others, it is best to get onto the forage before you think it is ready. To effectively graze this system, it would have been more efficient to have upward of 300 head of cattle. With this many cattle, you could graze larger paddocks and cover the field more quickly.

You could also split the herd into two grazing groups of 150 head to cover the field. This allows you to get the most benefit out of the field without letting the cereal varieties in the mix head out. One area of the field did not get grazed until late July, and the cereals had gone to seed.

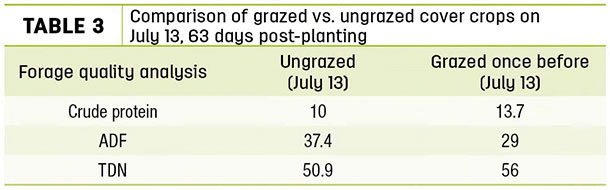

Forage quality in this section of the field is compared with another section on its second grazing on the same day (July 13, 2017), as shown in Table 3.

As you can see, the field that had not been grazed had lower crude protein and total digestible nutrients than the field previously grazed.

Most importantly, the class of cattle can play a major impact on the profitability of a grazing scenario like this. In the SARE project, the cattle used were spayed heifers. The cattle worked well as grazing units; however, it was noticed there was significant “riding” of heifers, which takes away from their grazing activity and can cause injury such as broken shoulders.

Using a stocker animal is preferable in this situation because it is in a growth period and can potentially get 2 to 3 pounds of gain per day. Using steers may increase your gain-per-day conversion as well as eliminate the issue of riding and injuries. If you are going to graze cows, it may be better to price the pasture on an animal unit month basis since daily gain will not be as high in the cows.

Cattle management considerations

Pinkeye was a management issue we observed in cattle in general this summer. From July to August, there was an increase in the number of cattle exhibiting symptoms of pinkeye. We believe some of this may have been caused when cattle put their heads down to graze and got pollen from the cereal grains into their eyes.

We have no answer on how to avoid this other than having a greater number of cattle to avoid cereals from heading out. Most of these plants were 2 to 3 feet tall. If they were closer to the ground, cattle would have less distance to put their head into them before reaching the greener forage below. In the SARE study, beardless barley and forage oats were used, so awns were not an issue.

One final thing to consider is how you will fence and water the cattle. In this situation, they had stock tanks and a water truck to fill those using floats so water was constantly available. This is a real management consideration, as 200 600-pound-to-700-pound cattle can drink up to 2,600 gallons of water per day and will need a constant source of water.

Using cover crops in a management-intensive system is a novel idea and, if executed well, can give you good gains on growing cattle while benefiting your fields. Consider the mix you will use, especially cereal varieties that may cause a higher risk of pinkeye.

Also make plans for fencing and water ahead of time, as this can be a substantial investment and management headache if water is not readily available in the area. Carefully choose what class of cattle you will use in the system and consider their gain potential and how you will price the pasture. ![]()

The research team of Carmen Willmore, Lauren Golden, Steve Hines and Joel Packham acknowledge much of this information is a result of a Western SARE Farmer/Rancher Research and Education Grant and thank the Purdy family and Picabo Livestock for sharing this information and knowledge.

-

Carmen Willmore

- University of Idaho Extension

- Email Carmen Willmore