Always determine the production objective of the operation before writing a nutrition plan. Ted McCollum III, Ph.D., Texas A&M AgriLife Extension, offered the following objective: “Under existing environmental and economic constraints, achieve the highest pregnancy rate possible in the shortest time possible. Production risk is managed with a good grazing plan, supplemental nutrition, herd health and genetics.”

McCollum recommended: “Manage nutrition by balancing grazing with forage supply, identifying when supplements are needed or beneficial, and then selecting and delivering the appropriate supplement.

Supplementation decisions should be based on the production objective, availability and nutrient value of forage, physiological status and size of the cattle, and current climate conditions. There is a cost benefit from making the right supplementation decisions.”

Balance grazing with forage supply

The primary component of economical nutrition programs is properly managed pasture forage. If efficiency and economy are expected of the supplementation program, an appropriate stocking rate is essential. A necessary major goal in grazing management is to leave enough forage in the pasture to protect the soil and maintain plant vigor.

Long-term heavy stocking rates weaken the forage resource, subject soil to erosion, reduce efficiency of rainfall capture and use, and degrade quality of water harvested from range and pasture watersheds.

“Conduct forage inventories in late June or early July, October and March to estimate available forage. Then make stocking adjustments to match the available forage supply,” recommended Robert Lyons in Texas A&M AgriLife Extension bulletin L-5400.

“Too often, a constant stocking rate is used for a county or region when it should be adjusted for changing weather conditions and other environmental factors that affect forage production.”

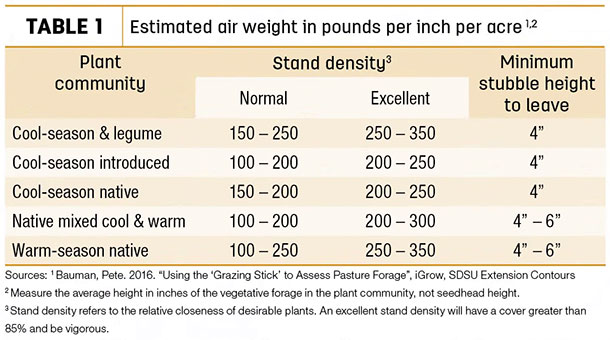

A grazing stick, available at most NRCS offices, offers a simple way to inventory forage. It is designed to measure average leaf height of vegetation with a yardstick-style ruler on one side. Using the measurements with the information in Table 1, pounds of dry material per acre is estimated.

Other information printed on the grazing stick allows estimation of suitable herd size, stocking rates and available grazing days.

Forage inventories provide estimates of quantity, but they don’t address quality. Samples of vegetation are clipped and sent to a laboratory for crude protein and energy content to determine forage quality.

“Reliable nutrient analyses require good sampling,” said McCollum. “Clip forage from only plant species and plant parts grazed by cattle. In pastures, take 10 or more samples across an area for every 40 acres and then composite the samples.

Take different samples for areas under different management such as fertilization, grazing intensities, forage species and trouble spots. On range, either sample across the unit or identify and sample a representative area.”

When supplements are needed or beneficial

“The purpose of supplementing grazing cattle is to correct a nutrient deficiency of the diet,” said Rick Machen in Texas A&M AgriLife Extension bulletin ASWeb-130. “Quantity and quality of available forage have as much or more to do with success or failure of a feeding program as the characteristics of the supplement.

For the commercial cow-calf producer, the production period with the greatest nutrient demand and the period of greatest expected nutrient availability should coincide.”

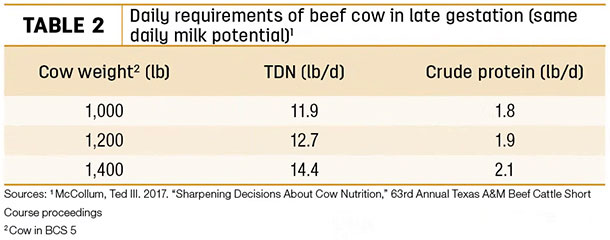

Cow nutrient requirements are governed by bodyweight, lactation potential, stage of production, desired body condition and weather. Effects of cow weights on daily nutrient requirements are demonstrated in Table 2.

A 1,400-pound cow requires 2.5 pounds of total digestible nutrients and 0.3 pound of crude protein more than a 1,000-pound cow on a daily basis. These requirements are for cows in late gestation with the same daily milk potential and a body condition score (BCS) of 5.

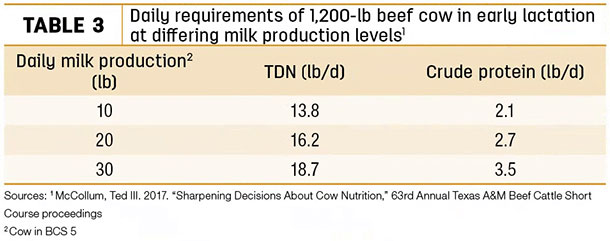

Breeds with higher milk production potential have greater year-round maintenance requirements. Daily nutrient requirements of a 1,200-pound beef cow in early lactation at differing milk production levels are shown in Table 3.

The beef cow’s nutrient requirements are the lowest during the mid-gestation, dry production stage. They steadily increase during late gestation through dry and early lactation. Nutrient requirements peak during late lactation.

“Greatest demand experienced by a cow during the production year is the first 60 to 80 days post-calving. During this period, cows are trying to recover from calving, reach and maintain peak lactation, cycle and rebreed; therefore, more attention needs to be given to their nutritional needs.

Heifers with their first calf at side while going through this process demand special consideration if high conception rates for the second calf are a priority. Body condition adjustments are most efficiently made during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy,” said Machen.

“Manage body condition scores so mature cows average a score 5 or better at calving,” recommended McCollum. “If cows are in BCS 5 or better at calving, a slow gradual weight loss is OK. If cows are less than BCS 5 at calving, then hold or increase weight after calving. To move a 1,200-pound cow in late gestation from BCS 4 to BCS 5 requires an additional 13.9 pounds of total digestible nutrients per day and 1.7 pounds of crude protein.”

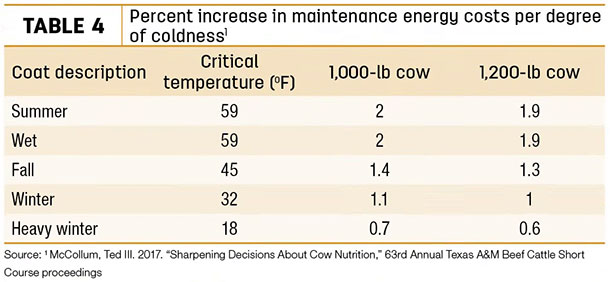

“Wet and/or cold weather can increase maintenance energy requirements to maintain body temperature,” McCollum continued. “Wind chill-adjusted temperature is used to determine additional energy requirements and is derived by subtracting wind chill temperature from critical temperature. Critical temperatures and percent increase in maintenance energy costs per degree of coldness are shown in Table 4.”

“Feed cattle supplement only when they begin to experience a nutrient deficiency,” said Machen. “It is important to maintain appropriate body condition on cattle because replacing lost weight or condition is very expensive and economically inefficient. If cows are in better than necessary condition, weight loss to the proper condition is acceptable and saves some feed expense.”

Selecting and delivering the appropriate supplement

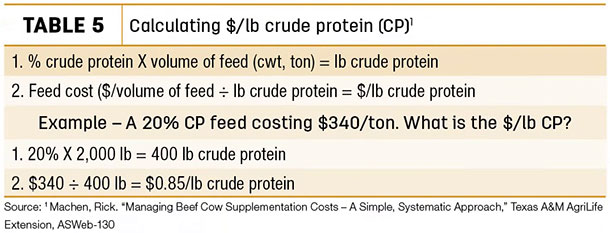

“Protein is often the limiting nutrient for cattle grazing dormant forages or consuming poor-quality hay and is commonly the more expensive feed nutrient. Base feed selection on cost per pound of nutrient rather than cost of a 50-pound sack or ton.

Calculating cost per pound of crude protein is demonstrated in Table 5. Comparing two feeds of different nutrient content strictly on price per unit weight is like comparing apples and oranges,” Machen emphasized.

High protein supplements of greater than 30 percent crude protein, fed at 0.1 to 0.3 percent of bodyweight per day, stimulate forage intake. Research results indicate the intake improvement is sometimes as large as 60 percent.

Increases in forage intake provide a large boost in energy and demonstrate why correcting a protein deficiency is usually the first priority in supplementation programs.

“In contrast, starchy, high-energy supplements such as cereal grains tend to reduce forage intake and digestibility,” said Machen. “The net effect is sometimes a reduction in performance. Energy supplements containing 10 to 18 percent protein and fed at 0.7 to 1 percent of bodyweight can extend a limited forage or hay supply without reducing performance.

“Between the high protein and energy supplements are general-purpose feeds, of which the 20 percent crude protein formulation is perhaps the most popular. Supplements of this type are an excellent choice when attempting to maintain forage intake and improve performance and body condition. Recommended feeding rates are 0.3 to 0.5 percent of bodyweight per day.”

“Research shows high-protein feeds can be fed as little as once weekly,” said McCollum. “There is an opportunity to reduce nutrition program costs by feeding weekly supplements once a week, twice a week or three times during the week. It is recommended this approach not be used with feeds containing urea or other non-protein nitrogen ingredients, medications or high levels of grain.”

McCollum summarizes the steps in managing cattle nutrition with the following bullet points:

- Adjust stocking rates to ensure adequate forage.

- Monitor forage quality.

- Monitor cow condition.

- If possible, group cows by needs (size, production stage, body condition).

- Supplement when most effective.

- Select supplement based on needs and nutrient cost.

- Reduce feeding frequency if feasible.

PHOTO: Body condition scores (BCS) are a good indicator of whether cattle are receiving adequate nutrition. Photo by Robert Fears.

Robert Fears is a freelance writer based in Georgetown, Texas. Email Robert Fears.