Body condition score affects all of the responsibilities of a productive cow in the herd and ultimately affects the beef enterprise’s bottom line.

Reasons to measure BCS

Body condition score or change in body condition is a more reliable way to evaluate a cow’s nutritional status than live weight or change in live weight. Most cow herds have a range in frame size and muscling that makes BCS a better measure of body fat than live weight. Live weight is also affected greatly by gut fill, pregnancy status, forage quality and forage availability. The BCS technique is easy to learn and can help with management decisions.

How to measure BCS

The BCS for beef cows is a subjective tool to evaluate cattle nutritional status and is assessed on a scale of 1 (thin) to 9 (obese). The first step in determining BCS is to know which areas of the body to evaluate (Figure 1).

Fat deposits are visible in the brisket, and over the ribs, back/spine, hooks, pins and tailhead.

The best way to start is to determine whether the cow is a BCS 5 or less than a BCS 5. If the last rib is not visible, the animal has a BCS greater than 5. If the last rib (13th rib) is the only rib visible, then the animal is a BCS 5. If multiple ribs are visible, then the animal is less than a BCS 5.

An animal with a BCS of 5 should look neither thin nor fat. The ability to understand what a BCS 5 looks like is a key skill to develop. More specificity is needed when classifying cattle into three groups of BCS that correspond to the 9-point scale: thin (1 to 3), moderate (4 to 6) and fleshy (7 to 9). Most cattle should fall into the moderate category. Once you are comfortable with the three-group classification, you can assess BCS on the 9-point scale.

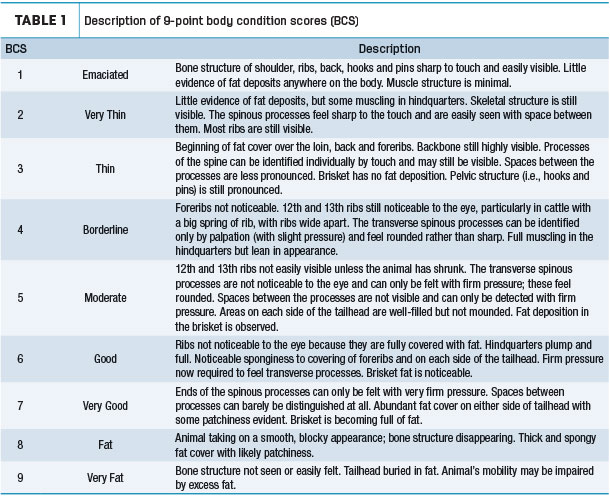

Table 1 provides a description of each BCS. The initial survey is best conducted from the side of the animal where all six of the evaluation points (brisket, ribs, spine, hooks, pins and tailhead) are visible.

Seasonal changes in condition score

The BCS of the beef herd will change during the year. The herd’s mean BCS is usually highest in middle to late summer, declines in the fall or winter, and lowest in late winter or early spring. Forage quality and quantity, as well as the cow’s stage of production, influence the variation in BCS. Cattle at either age extreme lose condition faster than other types of cattle, especially after calving.

Young cattle have growth requirements that must be met along with lactation requirements immediately after calving that negatively affect BCS. Old cows may have teeth issues that impair forage consumption and negatively affect energy intake and BCS.

When to measure BCS

Regular assessment of BCS in the cow herd is a good management practice. There are certain strategic times to measure BCS in cows that can affect overall productivity of the herd. Below are some critical times to assess cow BCS in order to make management decisions and affect BCS changes.

-

90 days prior to calving: This is the last opportunity to have cows gain BCS before the demands of calving and lactation begin.

-

Calving and breeding: Thin cows need to gain BCS to rebreed successfully; however, BCS gains during this period are costly and difficult to achieve because nutrient demand is highest at this time.

-

60 days prior to weaning: If cows are thin, calves can be weaned successfully to decrease cow nutrient demand and dedicate nutrients to BCS recovery.

- Weaning: This is the optimal time to recover cow BCS because of decreased nutrient requirements. Cows can be separated to provide additional nutrients to young and thin cows.

Production and BCS

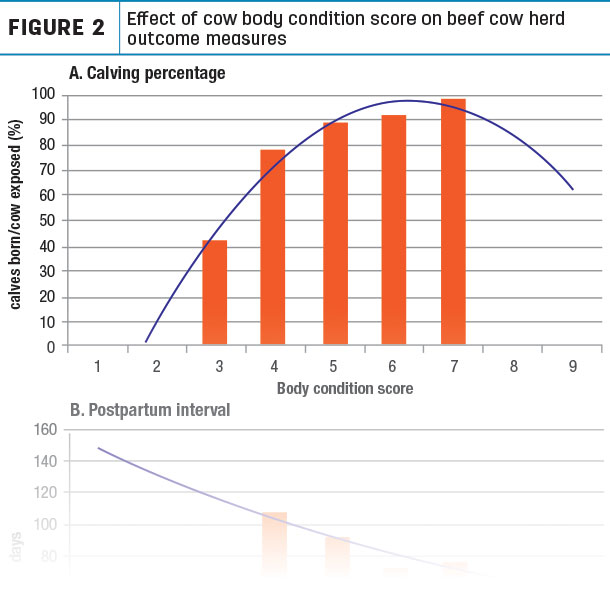

There is a direct relationship between cow nutritional status, BCS and cow herd reproductive performance. Summarizing data from four sources provides a nice data set to understand the relationship of cow BCS and production. Figure 2 demonstrates the relationship of cow BCS to five important reproductive and productive outcomes.

Click here or on the image above to view it at full size in a new window.

In each instance, improving cow BCS from thin/BCS 3 to moderate/BCS 5 improves the outcome measure. Trend lines are included on each graph to demonstrate the relationship of BCS and outcome.

Calving percentage (Figure 2A) depicts the number of calves born from all of the cows exposed to the breeding program, regardless of whether the cows became pregnant. Calving percentage is a measure of breeding and gestation efficiency; break points between BCS 3-4 and 4-5 are evident. Postpartum interval (Figure 2B) shows the number of days that occur between calving and establishment of the subsequent pregnancy. A production goal is to have a cow calve on an annual basis; calving intervals greater than 85 days do not allow for a calf on an annual basis.

The pregnancy percentage (Figure 2C) demonstrates the number of cows that became pregnant during the breeding season. A linear increase in pregnancy percent is evident with increasing cow BCS. Weaning percentage (Figure 2D) depicts the number of calves weaned from the total number of cows exposed to breeding the prior breeding season. The weaning weight (Figure 2E) outcome is expressed as pounds weaned per cow exposed to breeding in the previous breeding season. This measure takes into account all lack of performance in the cow herd from a reproductive basis. A distinct deficiency in thin cows with a BCS 4 or fat cows with a BCS 7 is clearly evident.

Economic impact

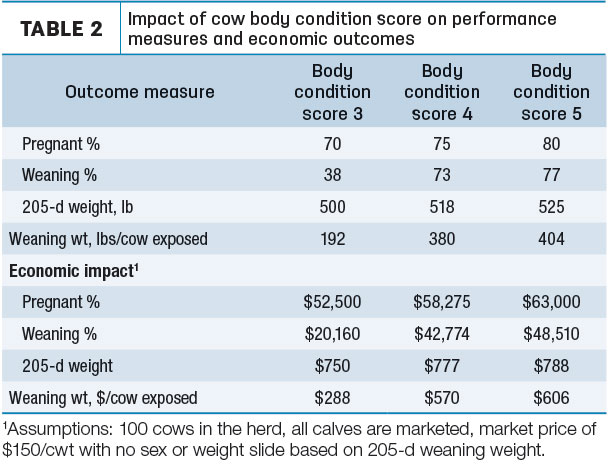

Ultimately, cow BCS and production outcomes must have economic relevance. Table 2 presents an interpretation of the economic impact different cow BCS (3 to 5) have on productive outcomes.

The outcome measures are of pregnancy percent, weaning percent and weaning weight per cow exposed from Figure 2; 205-day weaning weight is derived from the same data sources.

Because low BCS cows have decreased pregnancy rates, wean fewer calves, wean lighter calves and return less overall dollars to the herd, the impact of BCS on cow herd profitability is considerable. Certainly, estimations of revenue are sensitive to calf sale price, but it is undeniable that adequate cow BCS and thus adequate cow nutrition is imperative to profitability.

Summary

Routine assessment of BCS is the cheapest cow nutritional management system available and provides information to manage the cow herd for a high calf crop and profitability. A BCS of 5 or higher at calving and through breeding is needed for good reproductive performance.

Body condition score affects the cow’s ability to maintain herself, ability to become pregnant, maintain pregnancy and can negatively affect calf performance. The opportunity to negatively or positively affect a calf crop and the economic return from the calf crop ultimately starts with cow nutrition and BCS. ![]()

-

Matt Hersom

- Extension Beef Cattle Specialist

- University of Florida

- Email Matt Hersom