Most of the U.S. beef packing infrastructure was built in the 1980s. Cattle inventories in the decade of the 1980s averaged 108.3 million head, 15% greater than the 92.1 million head average of the past decade. The industry was characterized by excess capacity for many years as cattle inventories declined.

Over many years, capacity slowly exited the industry. In 2000, a ConAgra plant in Garden City, Kansas, burned and was not rebuilt; Tyson closed a plant in Emporia, Kansas, in 2008; and in 2013, Cargill closed a plant in Plainview, Texas. The National plant in Brawley, California, closed in 2014 but reopened as One World Beef in 2017.

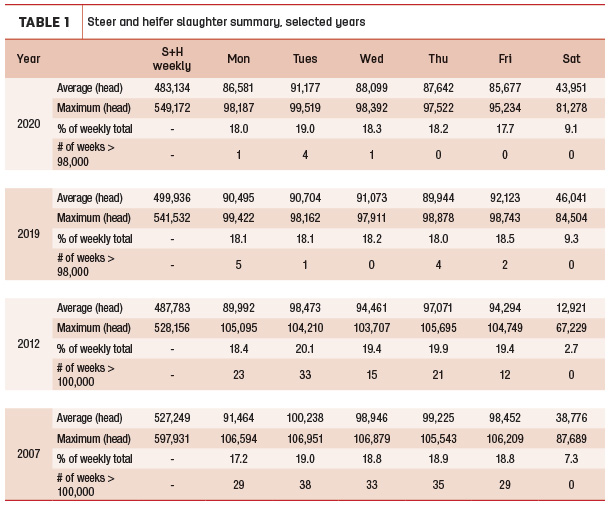

Table 1 shows characteristics of current steer and heifer slaughter for 2020 and 2019 compared to 2012 and 2007. The COVID-19 pandemic caused unprecedented disruptions in beef packing in 2020, so 2019 is included as a more typical year – although a single plant fire also caused disruptions that impacted operations in 2019, though the impacts were relatively short-lived.

Despite dramatic weekly volatility within each year, the general characteristics of 2019 and 2020 steer and heifer slaughter over the year were not substantially different. These two years are compared to 2012, the year prior to the Cargill plant closing and to 2007, the year prior to the Emporia plant closing. Total steer and heifer slaughter in 2012 (25.43 million head) was less than 2019 (26.1 million head) and fractionally higher than 2020 (25.3 million head). Steer and heifer slaughter in 2007 was the largest in Table 1 at 27.49 million head.

Table 1 shows the weekly average and maximum steer and heifer slaughter totals annually and for Monday through Friday in each of the years. Some aspects of slaughter have been consistent over time: Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday daily slaughter tends be consistently higher than Monday and Friday slaughter, and Monday slaughter is nearly twice as variable as the rest of the week, meaning there is more labor inconsistency on Mondays. It should be noted that the sum of the daily maximum slaughter levels exceeds the weekly maximum in each of the years in Table 1 by 4% to 11%. In other words, it is never possible for packing plants to maintain maximum daily capacity for an entire week.

Across these years, the change in overall slaughter levels are reflected, but with some interesting differences in capacity relative to cattle slaughter. Total slaughter in 2012 was less than 2019 and similar to 2020 levels, but had a total of 104 days of slaughter in excess of 100,000 head, including 23 Mondays, 33 Tuesdays, 15 Wednesdays, 21 Thursdays and 12 Fridays. The single day maximum in 2012 was 105,695 head. There has not been a single day steer and heifer slaughter total in excess of 100,000 head since 2013, reflecting the decline in total capacity. In 2020, there were a total of six days with daily slaughter in excess of 98,000, with a single day (Tuesday) maximum of 99,519 head.

In 2019, a total of 12 days exceeded 98,000 head, with a single day maximum of 99,422 head on a Monday. In 2007, daily steer and heifer slaughter was greater than 100,000 head a total of 164 days, with a single day maximum of 106,951 head. Most of managerial flexibility in beef packing comes from Saturday slaughter. Table 1 shows that Saturday slaughter accounted for over 9% of weekly slaughter in 2019 and 2020. This compares to 2.7% in 2012 and 7.3% in 2007.

The cyclical expansion in cattle numbers from 2014 to 2019 has now pushed cattle slaughter beyond packing industry capacity. It is estimated that annual average slaughter has exceeded capacity since 2016. Although cattle numbers peaked cyclically in 2019, feedlot production is just now at a peak in early 2021, partly as a result of pandemic delays in 2020. The Feb. 1, 2021, feedlot inventory was the highest of any month since February 2006. Feedlot inventories declined in March and April, but slaughter capacity limitations will slow progress in harvesting fed cattle in a timely manner.

Thus far in 2021, Saturday steer and heifer slaughter has averaged 49,359 head per week and accounted for 10% of weekly slaughter. Slaughter needs will be seasonally larger in the coming weeks, and it will be difficult for feedlots to get more current. It will be challenging to maintain, let alone push Saturday slaughter in the coming weeks. It now appears that it will take the remainder of the second quarter and likely much of the third quarter of the year to move the fed cattle industry into tighter numbers and relieve the capacity constraints that are limiting the fed cattle market.

This article originally appeared in the May 10, 2021, OSU Cow/Calf Corner newsletter.