To see how far beef production has come in 40 years, just ask any producer from early in that period what it meant to raise commodity beef. Better yet, said Troy Marshall, ask any customer before that period what it was like to eat commodity beef.

Marshall, director of commercial industry relations for the American Angus Association, said the era of commodity pricing and breakevens in beef production are a bygone era, and the cattle industry has flourished since moving on. Speaking to the Texas Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association, Marshall compared that commodity pricing “actually rewards those who produce below-average product to set an average price.”

“Commodity pricing is kind of like putting your finger on the scale – but not in favor of those producers who are creating value.”

The demand for beef is now about the eating experience. By moving to value-based marketing, the genetic merit of the cattle is a driving factor to more marbling, tenderness and a larger supply of higher-quality beef.

“If you take the seedstock business, every day when you sell cattle there’s a huge spread in price based upon the genetic merit of those cattle.

“In the feeding industry, not only do they get to capture the value of the superior management in health and genetics, for conversion and growth, but 75 to 80 percent of the cattle sold are on the contract grid basis. This is so they capture the amount of value per grid, or for yield, and for quality.”

The packing industry, Marshall concluded, has always differentiated the product based on yield and quality grades. The addition of the Certified Angus Beef brand, he said, has started a “value-based marketing revolution” continuing today. “There’s over 100 programs out there now, branded programs that are moving significant volumes of beef in our industry.”

Scoring genetic merit

With over a billion pounds of product sold under the CAB program, the reputation of beef in that program has grown extensively. But, Marshall said, “it wasn’t very quantifiable to know what our reputation was really worth in the cattle market.”

To deliver upon that goal, the AngusLink has introduced a Genetic Merit Scorecard that calculates genetic potential values – almost like a set of expected progeny differences (EPDs) – for a pen of feeder calves enrolled in the program. “What we do is take your historical bull data, and information in your bull battery and your current bull battery, and calculate using those bulls’ EPDs.” Genetic scores also take into account the influence of the cow herd on the calves and create benchmark targets appealing to feedyards buying calves.

A score is created based for beef, feedlot and grid, each ranging from 0 to 200. The 100 score is an industry average. When a score hits 125 or higher, and the herd is managed properly, at least 50% of those enrolled cattle earn CAB status.

Beef score predicts genetic potential for feedlot performance and carcass value, using EPDs, carcass weight, marbling and feed efficiency.

Feedlot performance score represents potential for post-weaning performance, accounting for average daily gain (ADG) and dry matter intake (DMI) EPDs.

Grid score predicts the enrolled calves’ potential for carcass grid merit, utilizing marbling, fat and ribeye area EPDs.

“As we started to roll this program out, there were really two questions,” Marshall said. “Do the scores work? Do they accurately predict the performance of the cattle going into the feedyard?”

“The exciting thing is: We know that EPDs work, and we know that our genetic tools are extremely good. So the GMS systems work extremely well.”

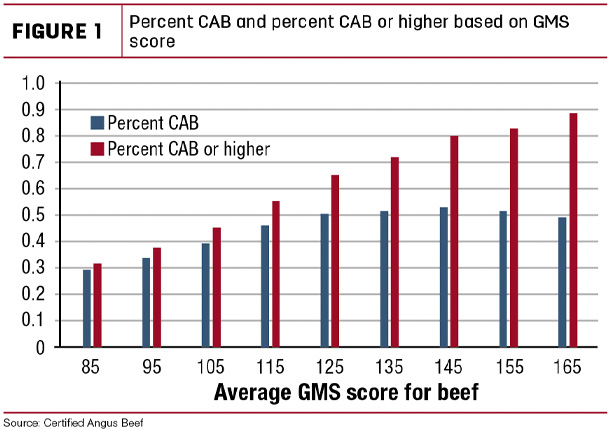

The parallel between GMS and Certified Angus Beef percentage, as well as carcasses that go CAB or higher, is reflected in the carcass data of 130,000 head (see Figure 1), where scores over 120 begin to show a majority hitting CAB.

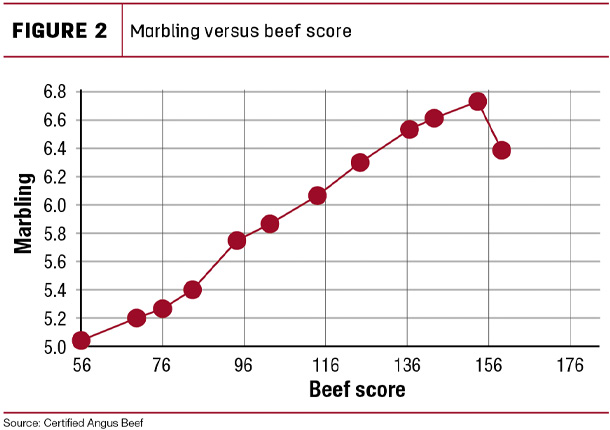

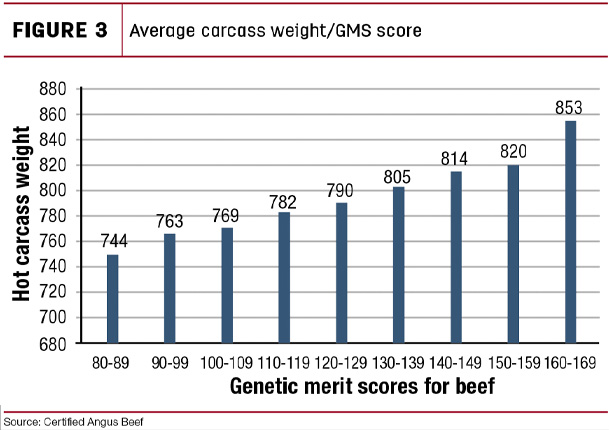

“The scores do a great job predicting quality grade,” Marshall said. “As scores go up, marbling goes up as well. And with average carcass weight, again as scores go up, weights go up.” (See Figures 2 and 3.)

Marshall said AngusLink has done its backup verification on the scores and their validity using video sale data. To double-check beef score values, AngusLink separated cattle in the top 50% and the bottom 50%. “The top score had 147, and the bottom was 121. The difference between those groups was 12 dollars per hundredweight, or 80 dollars a head. So the marketplace is starting to respond in seeing the difference in that.”

It all leads to a quote Marshall applies to former Texas football coach Darrell Royal.

“‘It’s not always about the X’s and O’s – but about the Jimmys and the Joes.’ And what the GMS gives your buyers is the opportunity that they can have the best game plan managing the cattle going forward, but they’ve got to have the right athletes or the right people in place. And also knowing where they’re at helps you target them to the right market and right management schemes.”

Strategy with the right cattle

Marshall said the market has an abundance of premium programs, all tailored for an audience of consumers expressing certain demands. Non-hormone treated or all-natural cattle, sustainable practice verified and preconditioned cattle are just some of the examples. All of those criteria-based programs are good for the demand requirements expressed by the processor and the consumer, Marshall said.

But over time, those programs go from unique to expected, and the producer is not paid the incentive for the work put in as an early adopter.

“The best example was our preconditioning protocol. Initially, there were pretty good premiums if you had VAC 45, or whatever the situation was, and as more and more of the industry adopted it and moved in that direction, the premiums got smaller until it became an industry standard, and at that point there’s no premium.”

GMS programs are different, Marshall said, since the technology grows its incentive as more producers participate in the network effect. Comparing it to Facebook or a social media app, the greater the subscribers, the larger the network, the more valuable it becomes.

“That’s the story with the GMS. The more people we have, the better job we do describing the genetics in the cattle. The better we can predict the performance, the more supply chains we can open up for you. The more confidence the feeders have.

“Today, one of their struggles is: They know 150 is better than 140. But they don’t know exactly how much more they can pay above 150 or 140. As they feed more and more of those cattle and work some of those things out, they’ll be much better at putting those into pricing equation.”

From a profit standpoint, the GMS program, Marshall said, encourages the right competition with proper values and gives all segments of the industry a joint target.

“We’ve got a lot of competition out there, and ultimately we have to create value, and one of the things the scorecard does is sets a genetic benchmark.

“One of the exciting things is how we’ve always talked about uniting the seedstock, the cow-calf, the feeder, the packer, with the seller being the important link, and I think we’re getting closer to that.”