Many inherit a fiddle in their grandfather’s will. Few know how to play it like a rockstar. I’m teaching my 3-year-old how to play the fiddle. Theoretically, that sounds great, but let me tell you, it doesn’t sound that great.

Most of the time, Huck is hitting notes on his fiddle that, to my trained ear, sound like nails dragging on a chalkboard. I know it’s going to be a decade of daily practice until he can play the fiddle half-decent. Just like Huck on the fiddle, I daily see parents struggling to groom their successors into farm management. To see this upcoming generation make mistakes is like nails on a chalkboard; many parents just would rather do it themselves. But why spend the next decade building your farm up, if your successor isn’t going to be able to manage the farm properly until a decade after your funeral?

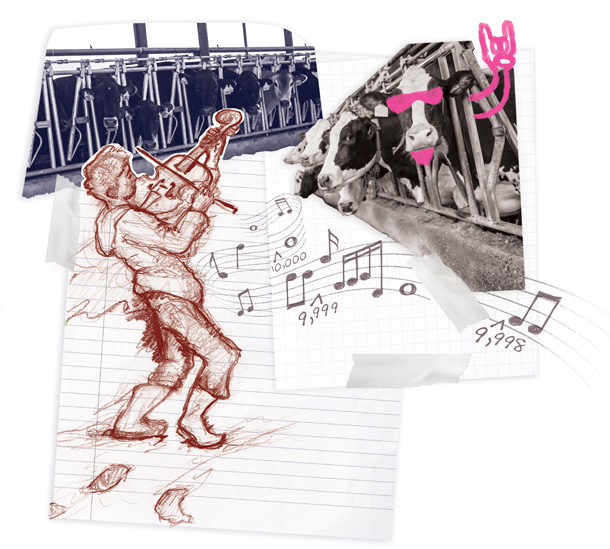

It used to be any half-decent musician could play music in bars for a living. It used to be any hard-working farmer could make a living milking cows. Now you need to be a rockstar to do either.

Malcolm Gladwell wrote a best-selling book called Outliers: The Story of Success. In it, he roughly said that the one thing that sets the masters apart from the rest is 10,000 hours of practice. “Ten-thousand hours is the magic number of greatness,” Gladwell wrote. It isn’t raw talent or upbringing but hard work that separates the wheat from the chaff.

There are a lot of kids who will take high-school band and carry a violin (aka fiddle) home on a school bus. But very few will become rockstars. The same thing is true with dairy farming. There will be a lot of kids who put milkers on cows after school. But very few will become rockstar dairy farmers and be able to make a living doing it. They will not be able to compete with those 30,000-cow dairies in a decade’s time.

Now, any grandfather can leave their fiddle to their granddaughter or grandson in a will. But what good is it if they never really learned how to play the instrument? It doesn’t matter if you inherit a $10 million Stradivarius or a $100 fiddle from a pawn shop. If you don’t know what you are doing, it will be obvious. It’s the same thing with dairy farming. It doesn’t matter if you inherit a 200-cow or a 2,000-cow dairy. If you don’t know how to manage that farm at a sophisticated level, the results will be obvious and ugly.

A master can make any fiddle sound good – if he knows what he is doing. It’s the same thing with a dairy farm. It doesn’t matter the size of the dairy any manager inherits; it’s their abilities to get the little things right that will determine the outcome. Sure, it would be nice to inherit a rockstar’s fiddle or a dairy that is worth $40 million, but what results can you crank out of what you have right now? Rockstars start from the ground up. So do rockstar dairy farmers.

There is a difference between being a farm employee and a farm manager. There are a lot of 35-year-olds who have the same job description as when they were 25. Let’s take farm financials as an example. Many farm patriarchs or matriarchs throw the farm’s financials into their grown child’s face and expect them to make sense of the numbers. The parents quickly get frustrated that their successor, who is turning 40, doesn’t know what the numbers mean yet. “They should know that by now,” they say.

But the reality is: The son or daughter may have never spent any depth of time with the farm financials – and in many cases, the farm books have been kept secret. Instead, the son or daughter has spent the majority of his or her time needling cows and fixing equipment, which they do extremely well, by the way. And why not, since it’s the same job description from the time they were in their 20s, right? Whether it’s playing the fiddle or analyzing the farm’s financials, if you don’t get enough time to practice and learn how to do it, you’re not going to do it very well. For many parents to expect their sons or daughters to take over financial decisions suddenly after a medical emergency is as foolish as throwing a fiddle into their hands and expecting them to magically make music out of it.

Another example I see repeated on many farms is Mom’s role as bookkeeper. Many sons in their 30s see their mom spend time plugging data into a computer and spending way too much time on details they think don’t matter. A job that should be done within two hours is taking Mom 20. But they don’t say anything because they know saying so would erupt a volcano. The sons just think, “Whenever I take over bookkeeping, I’ll use a different software program and do it a different/better way.” It won’t take much to replace Mom with someone who can do a better job, faster, right? Wrong.

It is one thing to watch someone playing a fiddle. It probably looks easy. It’s another thing to actually hold that fiddle in your hands and play it. Believe me, the first time you do it, it’s not going to be sweet. It’s the same with bookkeeping or any skilled job on the farm. It takes a lot of mentorships and hard work to get that 10,000 hours of experience needed to get to a level of sophistication where you’ve mastered the craft.

This goes way beyond bookkeeping. There are roughly 10 jobs on the farm, ranging from trading commodities to negotiating the purchase of equipment/inputs, that simply can’t be hired out to a third-party service. These are skills that require 10,000 hours of experience to really feel confident doing them.

My suggestion is that a son or daughter spend 5,000 hours making out the checks before they have check-signing authority, so they learn how money flows in and out of the farm. You can teach accounting at an agriculture college. But the wisdom on how to juggle the bills can’t be taught by a professor. It must be taught by a parent looking over their successor’s shoulder. It isn’t an activity mastered overnight. It takes a decade. Like playing the fiddle, it takes 10,000 hours of doing it to become good at it.

It’s easy to plug in data into a computer software program. But during tough times, dairy farmers often must prioritize paying bills and somehow make 1+1 equal 4. What is equally hard is when milk prices are sky high and how to prioritize spending, and then getting the farm bulletproof for the next time milk prices hit the floor. You need a decade to experience both market cycles. How many times have you seen a farmer inherit an impressive operation and then within 20 years, run it into the ground? Why is that? It’s because parents groomed a great tractor mechanic but didn’t groom a successor to understand how money flows in and out of the operation.

Now you can hire someone to plug data into a computer. But you can’t hire someone to make management decisions like what bills get paid first. You can hire an accountant, and they’ll record the data, and maybe give some off-hand advice, but the skill set to be a good CFO for a lean dairy can’t be hired. That is a skill set many will say they can do, but few have the skills to be able to do it.

Unlike bread and milk, humans don’t come with “best before” dates. We can fantasize about our 100th birthday party, but it’s more likely you’ll get tragic news you don’t want to hear from your doctor sooner than that. It takes a decade to groom a son or daughter in the finer details of farm management, like managing the farm’s finances or doing commodity purchasing training. Starting to train your successor how to do these jobs after you’ve been diagnosed with cancer is a surefire way to ensure the farm won’t be successful in 2050. Your kid might be a hard worker and want to farm, but you didn’t groom him or her into the role. Ultimately, you failed as a farmer and a parent. It takes 10,000 hours of experience and isn’t something that can be taught as you are undergoing chemotherapy or in the hospital. Grooming your successor to do the critical jobs on your farm has to start yesterday.

Anybody can hold a fiddle, very few can make sweet music out of it. Any good farmer can gift his kids a tractor, and any great farmer can teach them how to drive that tractor like a pro, but few are truly successful in teaching them how to make that tractor pay for itself.

Want to learn more? Go to Agriculture Strategy or call (800) 474-2057 for more information.