When I visit with forage producers about hay moisture in square bales, the top concern is spontaneous combustion and fire risk, followed by mold and mycotoxins and heat damage.

Recently, in central Nebraska, I have heard about more hay bale fires. So I started wondering how well the producers I consult with were doing on moisture management of their hay. Upon reading more literature, I began to see increasing mention of “brittle” hay. The premise being hay that is too dry is fragile and breaks during baling. The loss of the delicate leafy portions of the forage results in protein and overall forage quality losses. Furthermore, brittle hay processed through a batch mixer often becomes dusty, resulting in more feed losses.

So the first thing I did was gather hay reports (n = 4,017) sent to Ward Laboratories Inc. in 2021. I only included samples that were described as hay by the producer sending the sample. Then I looked at the moisture of those reports (Figure 1).

Optimal was defined as hay having a moisture between 14%-18%. Brittle hay was any sample with less than 14% moisture. Finally, heat risk, indicating risk for mold, mycotoxin, heat spots and the most dangerous, spontaneous combustion, was divided into moderate and high risk. Moderate risk was any sample with a moisture between 18%-22%, and high risk was any sample with moisture greater than 22%. Of course, specific bale types have different optimal moisture recommendations. These values were used to gain a general understanding.

Figure 1 shows that 13% of samples were at risk for heat damage or combustion. This number may seem low; however, it did surprise me. Imagine if 13% of all stored hay bales caught on fire! We are seeing reports of low hay inventory now, just imagine how damaging this could be. Furthermore, we certainly aren’t doing enough to evaluate our mold and mycotoxin risks if 13% of baled hay has such high moisture levels.

Only 15% of hay samples analyzed were within the optimal range of moisture to reduce heating risk and optimize forage quality. With such a small proportion being optimal, it would appear we have room for improvement. The brittle hay samples were the most prevalent hay samples at 71%. The surprisingly high number of brittle hay samples prompted a deeper look at the forage quality in optimal moisture hay samples versus those considered to be brittle.

Subtle difference in forage quality

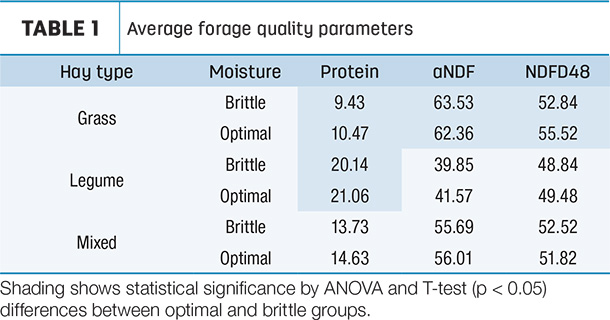

All samples were analyzed using NIRS Forage and Feed Testing Consortium calibrations. Forage quality parameters were evaluated for differences between hay samples with optimal moisture and those considered to be brittle. Forage quality parameters included crude protein, amylase-treated neutral detergent fiber (aNDF) and neutral detergent fiber digestibility at 48 hours (NDFD48).

The average quality parameter values were evaluated for statistical differences between means of brittle and optimal moisture hay samples. Further, because protein and fiber content are quite different in alfalfa than in grass hay, samples were evaluated within three groups: grass, legume and mixed hay.

Table 1 shows that no forage quality parameters were significantly different at brittle versus optimal moisture levels in mixed species hay samples. However, in grass hay, aNDF was lower by only about 1% in optimal moisture hay. While this may not seem to be a substantial difference, it was statistically significant and coincided with a statistically significant difference in NDF digestibility. Furthermore, protein was also higher in samples with optimal moisture levels. In legume hay, optimal moisture samples did have statistically significant higher protein than those considered to be brittle.

Management implications

With these results, we conclude that in grass hay, optimizing moisture can improve forage quality parameters. The importance of moisture was specifically significant in grass hay. This is interesting as most of the literature covers effect of moisture on forage quality in alfalfa. This data shows that in legume hay optimizing moisture can increase protein concentrations. However, other quality parameters were not impacted by moisture levels in legume hay.

These forage quality differences are minor. Yet, it is key to remember when looking at samples from various producers under various circumstances. Each sample was managed differently. Understanding these slight differences can help us make better management decisions about hay harvest and baling moisture.

In other words, some samples may be fresh hay samples, some may have been stored outside over the winter, others may have been stored in a barn or under a tarp. There may have been different baling practices implemented such as conditioning. All these factors can affect protein and fiber content of a forage.

However, a subtle difference when large robust sample groups are examined could mean a greater impact for a forage producer who manages his moisture with more precision to avoid both fire risk and brittle hay. Holding all other factors influencing forage quality equal, how much more protein could be held in your hay if leaf losses were reduced through optimizing baling moisture?

In conclusion, heat damage and spontaneous combustion risks should always be at the forefront of hay moisture considerations. However, overdrying can diminish forage quality. Overall, focusing on baling at optimal moisture levels might be one way forage producers can improve their forage quality.