The start of a new forage year is always filled with much anticipation – will it be a record-breaking year in terms of yield? Will the quality match or surpass the previous year? Will we be able to temper high commodity prices with high-quality forages? Will weather conditions force us to try new forages or consider revising our cropping plans? There are so many unknowns in the early stages of the cropping year, but what is certain is: Forages form the foundation of our rations and, therefore, must be the primary focus.

As a general rule of thumb on a dairy operation, most would agree the statement “Feed is 60 percent of the costs” is relatively accurate. As a consequence, dairy producers are always looking for ways to reduce purchased feed costs, and the first line of sight should be directed at the fields where the forages are being grown. The two most important nutritional factors to building profitable feeding programs for long-term optimal cow health and performance are forage quality and consistency.

When it comes to evaluating the quality of the forages that have been harvested, quality is much more than the protein level of the haylage or starch level in the corn silage. While sugars, starches and proteins are highly digestible in most plants, it is the variability in fibre digestibility that sets forage apart and makes them more challenging and complex.

The fibre, more specifically the neutral detergent fibre (NDF), can provide a significant amount of energy to help meet the caloric requirements of today’s high-producing herds, but it all depends on how digestible it is. In general, 60% to 80% of forage NDF is potentially digestible in the rumen, while the remaining portion is completely undigestible, as shown in Figure 1.

However, NDF is digested more slowly, and while it may remain in the rumen for 30 to 40 hours, in that time only 40% to 60% of the NDF is actually digested (digestible NDF) and converted into energy and microbial biomass. It is only the digestible NDF that is a valuable source of energy, and an excess of undigestible NDF will restrict feed intake. Therefore, having an accurate measure of forage NDF digestibility will not only determine how much energy can be extracted from the forage but also how much of that forage the cows can consume.

Recent advances in the way in which NDF digestibility is measured is shedding new light on how forages perform within the cow’s digestive tract, allowing nutritionists to optimize the use of on-farm forages and feeds for improved predictability. In the past, a single time point estimate of 24, 30 or 48 hours was used to determine NDF digestibility (NDFD). However, the cows have always told us that NDF digestion is much more dynamic than that, and a single time point was not able to capture the variability. A new methodology that tracks and plots both the rate and extent of NDF degradation in the rumen over a full 240-hour period has been developed to provide real-time NDF digestion profiles for forages.

Figure 2 helps to visualize this concept of dynamic NDF degradation in the rumen for two different samples of mixed alfalfa/grass haylage.

In Figure 2, we can see that Haylage A (the orange line) follows the “average” curve (the blue line) for NDF degradation quite closely – both the rate at which it digests and how much of the NDF is digestible is average or slightly above average. In comparison, it is obvious Haylage B digests much slower than average and much less of the NDF in that haylage is potentially digestible.

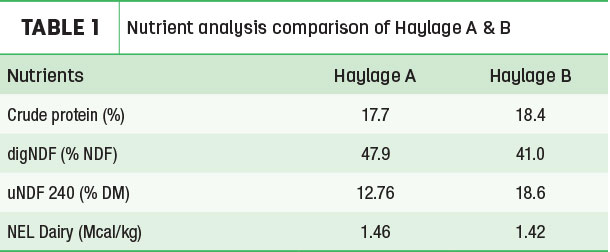

Not only will the energy be significantly higher in Haylage A, as seen in Table 1, which could lead to lower purchased feed costs, but we would anticipate higher intakes, leading to even more available nutrients to make more milk at the least cost.

What value does this bring to dairy producers?

1.Energy: Digestible NDF is one of the major energy sources for ruminants. It provides rumen flora (bugs) with a very steady form of safe energy. At $7-per-bushel corn prices, producers cannot afford to not capitalize on the potential energy in their forages. While the weather/growing conditions, soil fertility and variety selection all play a role, harvesting at the correct maturity is hands-down the key driving force behind maximizing digestible NDF in forages. Once it is harvested at the correct time, proper ensiling and storing is needed to ensure this energy is properly conserved.

2.Improved intakes: Digestible NDF and, conversely, uNDF240 impact dry matter intake (DMI). Every additional unit in NDFD is associated with 0.17 kilogram per day more intake and 0.23 kilogram per day more milk yield. As a means of fine-tuning diets, especially for fresh and high-production cows, evaluating forage uNDF240 in the diet as a percent of cow bodyweight can be another means of anticipating changes in DMI when we move into different forages. We can take it a step further and look at the physically effective UNDF240 (peuNDF240) within a diet, as that marries the physical and chemical characteristics we know have a significant influence on DMI. This requires knowing the Penn State Particle Separator results for each forage and feed on-farm, as well as an accurate measure of uNDF240.

3.Improved predictability: When looking at NDFD curves, the first 40 hours is most telling in terms of how it will act in the rumen. Using that information gives nutritionists greater insight into how to balance the ration more precisely to optimize the use of on-farm ingredients to ensure predictable production at the best cost, consistently. For example in Figure 3, looking at how NDFD tracks below average for the first 48 hours in Haylage B, if there had been straw in the diet previously, it could be removed now, as this forage already digests at a slower rate.

By having this information, it becomes easier to combine different on-farm forages to more effectively synchronize a steady supply of energy to the rumen microflora.

4.The right feeds to the right groups: Being able to evaluate and compare all on-farm forages in terms of the amount of digestible NDF they can contribute is key in ensuring the right feed is fed to the right group on-farm. It is important to only compare results within the same forage type – do not compare NDFD curves of legumes versus grass or corn silage versus legume. Take the time to review the results with your farm team, including your agronomist and nutrition consultant. Forages with higher NDFD digestibility are much more suitable for transition and high-producing cows, as they will provide more energy and higher intake potential while leaving less-digestible forages for low-production groups or heifers makes most sense from an economic and nutritional standpoint.

Advancements are continually being made in terms of forage analysis and all of the factors that influence the digestibility of forages, but it doesn’t end there. Challenges within the dairy facility – be it heat stress, ventilation, overcrowding, empty bunks, water supply, poor stall design, just to name a few – can compromise the value that can be captured from high-quality forages, so the bigger picture always needs to be evaluated as well. Cows are our most critical reviewers of the rations put in front of them, but the signals they send us can give us clues as to whether the issues are nutritional or non-nutritional.

The composition of forages provides valuable information when building rations. Many factors go into making profitable milk, but working with a trusted adviser, along with accurate and complete forage analysis, can change the statement of “Feed is 60 percent of costs” into “Forages drive profitability.”