To read this article in Spanish, click here.

Everyone in the dairy farming world knows how mastitis can negatively affect operations.

Mastitis involves inflammation of the mammary gland, or udder, in association with an infection. Most infections are caused by bacteria that pass through the teat canal and colonize the tissue responsible for making all the milk components – mammary epithelial cells. This is followed by the classic signs of inflammation, such as an increased somatic cell count (SCC), pain, heat, redness and swelling of the affected area. Detecting these signs is the first step to creating an effective prevention and control program.

Based on the symptoms of inflammation, mastitis can be categorized as clinical (milk appears abnormal) or subclinical (milk appears normal). For clinical mastitis detection, forestripping (i.e., the process by which the first streams of milk are expressed from each teat before milking) at the beginning of the milking routine is fundamental, as more than 50% of the cases involve abnormal milk (watery appearance, flakes or clots). For subclinical mastitis, enrolling the herd in programs that measure SCC regularly is fundamental. Using the California Mastitis Test (CMT) is another tool farmers can use to detect subclinical mastitis.

Detection of clinical mastitis by forestripping at the beginning of the milking routine. Photo provided by Maria Fuenzalida.

Detection of clinical mastitis by forestripping at the beginning of the milking routine. Photo provided by Maria Fuenzalida. After mastitis has been detected, the next step is identifying the mastitis-causing bacteria. Some dairies have laboratories where milk samples are plated onto selective agars that allow farmers to discriminate among gram-positive or gram-negative bacteria or to determine the bacterial genus – streptococcus spp or staphylococcus spp. Farmers without on-site testing can collect milk samples and submit them to a qualified milk quality laboratory for identification. Only a qualified milk quality laboratory can speciate a mastitis-causing bacteria – such as Streptococcus agalactiae or Staphylococcus aureus.

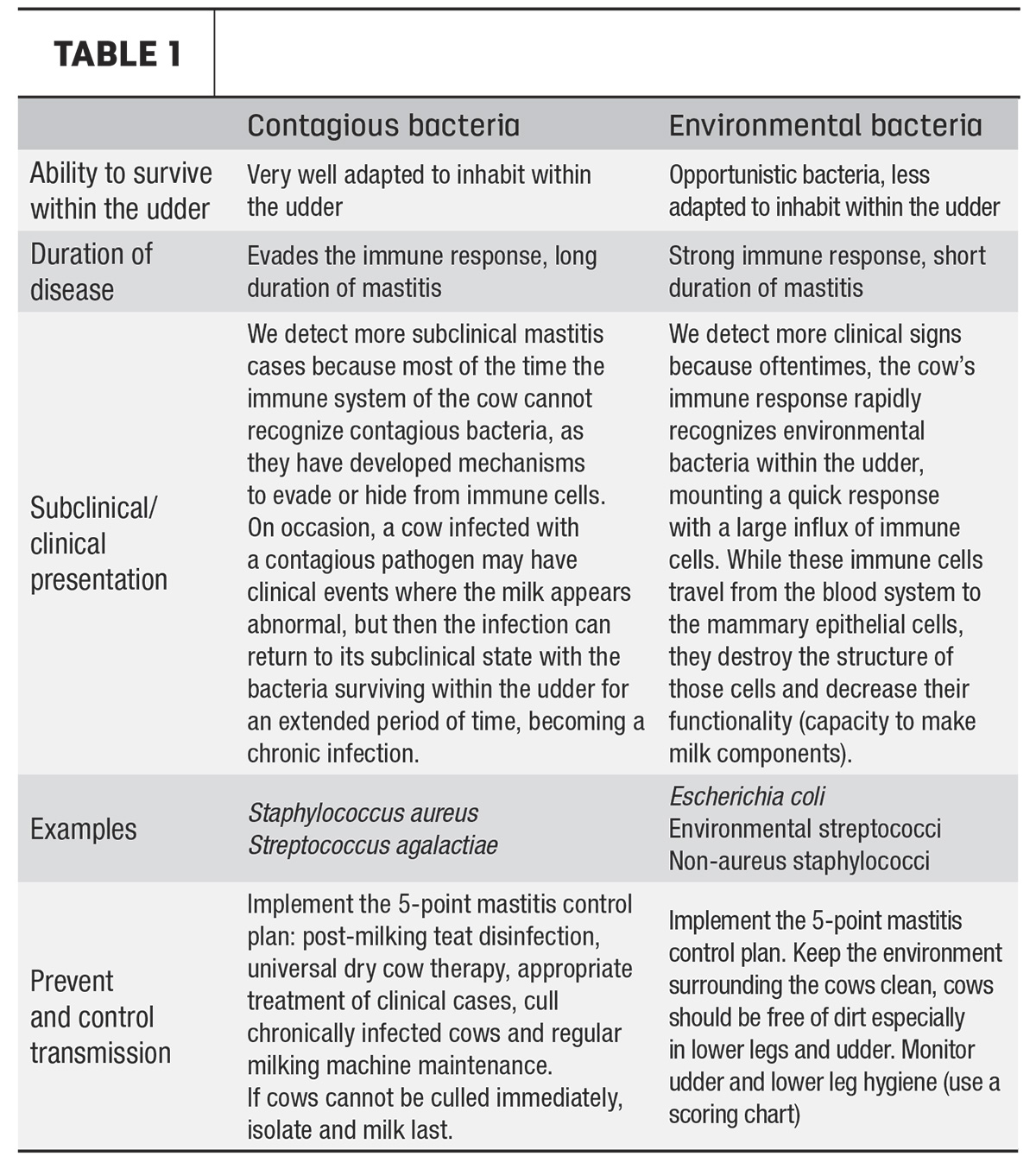

Once the mastitis-causing bacteria has been identified, it is possible to start developing strategies to prevent and control mastitis. Additional sources of information can also help to understand what mastitis-causing bacteria are in a dairy; one example is bulk tank SCC and microbiological results from bulk tank samples. Mastitis-causing bacteria are often classified as either contagious or environmental, but it has been proven that some environmental bacteria can behave as contagious bacteria – a good example of this is Klebsiella spp. Contagious bacteria survive within the udder, so the only possibility for transmission to other cows is through contact with contaminated milk. Environmental bacteria are found everywhere in the dairy farm, in manure, sand and bedding. Keeping cows as clean as possible will reduce teat canal exposure to environmental bacteria. The ongoing challenge of decreasing exposure to environmental bacteria is combatted by ensuring the cows' teats are clean and dried before attaching milking units. This is summarized in Table 1.

Ensuring that milking units are attached to clean and dry teats is essential for mastitis prevention. The next step is to focus on the milking routine. Dairy farmers need to make sure that only well-trained personnel milk cows.

The core milk quality practices during the milking routine are: Forestrip to check for abnormal milk, pre-dip 75% or more of the teat surface with a contact time of 30 seconds or more, and dry each teat thoroughly with a non-shared towel. Next, attach milking units after 60 to 90 seconds of stripping and dipping and remove the milking units (automatic take-off helps to prevent overmilking). Lastly, apply a post-dip solution that covers 75% or more of the teat surface.

If the udder or teats are covered with dirt or manure, cleanse the area before forestripping. Do not use water to clean floors or cows during milking, as bacteria travel more easily on wet surfaces than on dry surfaces.

Veterinarians need to be included to develop a mastitis prevention and control program that will fit the needs of each dairy farm.

Mastitis is a dynamic disease that requires continuous monitoring. Each farm needs an interdisciplinary team of well-trained people to develop and implement a successful mastitis prevention and control program.

The author would like to thank Jacob Backes for reviewing this article.