Stocking density has been a common topic of conversation on dairies for many years. When tiestall barns were the norm in the dairy industry, we had “switch cows.” We had more cows than stalls, so we were required to “switch” cows from an outside or side pen to a tiestall to milk. Now with most cows living in freestall barns, we still experience a similar situation. Instead of measuring stocking density by the number of switch cows, we represent it as the percentage of cows compared to the number of stalls in a pen. If we have 120 cows in a pen with 100 stalls, this pen has a stocking density of 120%.

Overstocking is a term often used for any time the stocking density is over 100%. Across the industry, there are different philosophies and opinions to what is the most profitable stocking density. As with most things, the correct answer to the most profitable is “It depends.” More importantly, the correct answer changes over time.

To begin, we must understand why we might overstock. In both tiestalls and freestalls, overstocking allows us to milk more cows in a given amount of infrastructure. With these additional cows, we generally produce more milk within a given amount of infrastructure. Using financial vernacular, we spread our fixed costs over a greater number of hundredweights. Fixed costs on a dairy include the physical infrastructure (barns, parlors, equipment, some labor). This more milk leads to more income. However, does this more milk lead to more profit? Not necessarily.

Next, we can consider why we wouldn’t overstock or what the limitations of stocking density may be. When we milk more cows, we spread our fixed costs, but our variable cost continues to climb with the number of cows. The most notable variable cost on a dairy is feed. To add to this, when we add cows to a pen, generally every cow will produce incrementally less milk and have a lower feed efficiency. This is often due to the reduction in average lying time and eating time.

We have the counteracting forces. On one side, when we overstock, we benefit from spreading our fixed costs over more milk and, most likely, greater income. On the other side, we have higher feed costs and continually dropping performance with higher stocking density. Again, using financial vernacular, we have a diminishing marginal return from increasing stocking density. So how can we tell what the most profitable stocking density is? It is where the marginal income (more production) of adding an additional cow to the pen is equal to the additional costs (additional feed and reduced production) that accompany that cow. How do we find this optimal?

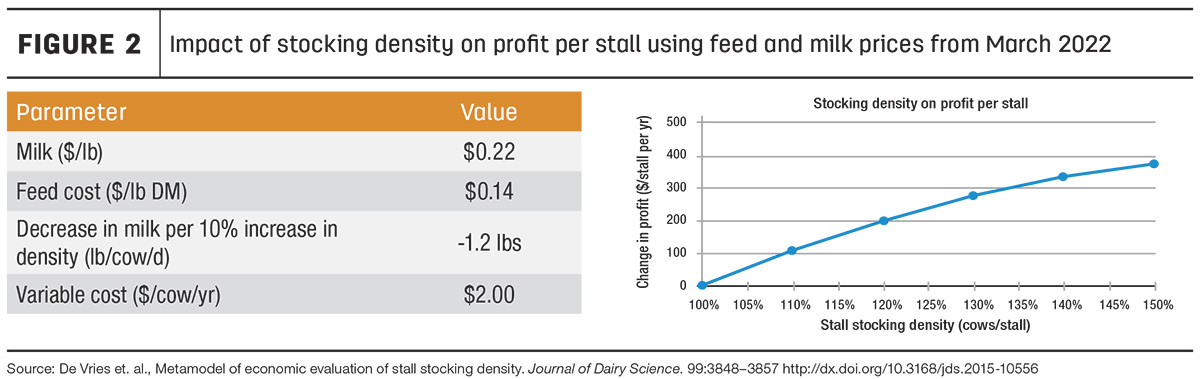

Thankfully, some researchers at the University of Florida did the heavy lifting. In their research, they considered the largest economic variables that play into stocking density. These included milk price, loss in milk production, feed price, probability of a cow being culled, probability of a cow being inseminated. Using their model, we can plug in some current prices and assumptions to approximate the optimal stocking density. These scenarios are represented in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1 represents the current scenario. As we are all aware, we have entered into a period of sluggish milk prices and record-high feed prices. In this analysis, I assumed we would lose about 1.2 pounds of milk per cow for every 10% increase in stocking density. This is pretty close to my experience in the field. Based on this scenario, the optimal stocking density would be around 110% and would garner a modest $5 more profit per stall per year.

On the flip side, last March, when we were experiencing luxurious milk prices and relatively high feed prices, the model would suggest we increase our stocking density past 150% and increase our profit per stall per year to almost $400 if we increase stocking density to 150%. Although practically this may be unreasonable, it makes some mathematical sense. Because milk prices were so high, we can justify the extra feed expense and lost milk easily by adding more cows.

There are several caveats with this analysis to note. First, milk components are not considered. Often, when fluid milk decreases due to overcrowding, we see changes in our milk component concentrations as well. Moreover, when we enter extreme situations of stocking density, the assumptions we made around the probability of culling and reproductive performance become unreliable. We often see that when we reach extreme levels of overcrowding, more injuries and accidents occur. Not to mention the extra stress on employees and cows.

Also note one of the largest factors that determine the profitability of stocking density is the expected milk production loss from increasing stocking density 10%. In this analysis, I used 1.2 pounds per cow per day. If properly managed, this number could be lower. Increasing the management intensity around freestall comfort, flooring and traction, heat abatement, bunk management, milk quality, etc., will lend to the ability to mitigate the negative effects of overstocking.

This brings us to the solution that was presented at the beginning of the article. The optimal stocking density changes over time. Generally, if income over feed cost is large and there is a wide margin between feed and milk, we should milk more cows. When the margin between feed and milk is tight and income over feed cost shrinks (like right now), we should consider lowering our stocking density.