Illness and death of animals are frustrating, no doubt. It has been said, “If you’re going to have livestock, you’re going to have deadstock.” While it may be a cliché, it is an unfortunate reality. Despite the production losses and negative effects on profitability, creating a positive outcome is still possible. Knowing how to capture helpful information from troublesome scenarios can reduce the occurrence or impact in the future. It would be a missed opportunity not to learn from the circumstances when disease occurs.

It may seem harsh, but reframing the words of the earlier saying goes, “If you can’t afford deadstock, you can’t afford livestock.” The initial takeaway from this statement is the financial consideration. Being prepared for the costs due to disease itself is important but so is having the ability and willingness to make investments in finding out what went wrong when it goes awry. It is difficult to think about in the moment when it feels like it would be “throwing good money after bad,” but it is critical to commit resources to the long-term health of the animals and the success of the operation.

The broader importance of the earlier remark is knowing how to recover value from the disease situation through diagnostics. In addition to working with a veterinarian on the specifics, it is good to have an idea about which animals are the best to select for samples, how to preserve the specimens and what information is useful for the laboratory. Having assistance from producers helps ensure that diagnostic submissions are not a wasted endeavor that is counterproductive in terms of both labor and expense for everyone involved. Diagnostic workups can yield valuable insight if they are conducted properly, and that process starts early in the disease outbreak. Indeed, it may seem costly, but the better the process is handled in the beginning, the better the return.

General guidelines

Regardless of the disease condition, some basic principles apply. The best candidates to sample are always untreated animals that have clinical signs consistent with the larger problem and have been displaying those clinical signs for only a short period of time. As infections linger, opportunists or secondary bacterial infections may take over for the inciting cause, making detection of the initial culprit challenging. Likewise, identifying the problem of an outlier through poor selection is not helpful in generating solutions or preventative strategies for the herd. Some diagnostic techniques require bacteria to be alive for the testing, and antibiotic use may disrupt the procedure by killing the organism.

Samples should always be stored cooled at refrigeration temperature but not frozen. They should be shipped with an appropriate number of ice packs depending on the ambient conditions and sent to arrive at the laboratory the next day. The interval between collection and arrival at the laboratory should be kept as short as possible. Any descriptions about the circumstances occurring on-farm should be communicated to a herd veterinarian and included on the submission form because this can be helpful in selection of appropriate testing by personnel at the lab. The information provided can also be correlated with laboratory findings to provide relevant responses and solutions for the disease occurrence.

Bovine respiratory disease (BRD), sometimes referred to as pneumonia, and infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis (IBK), known as pinkeye, are two common diseases that contribute to losses in dairy cattle and for which proper diagnostic processes can produce tremendous awareness. In both conditions, multiple organisms including some with strain variation are thought to have a role. Being able to capture the dynamics of the condition through a well-conducted investigation will help ensure the correct causes are identified. The active engagement of producer, veterinarian and diagnostic laboratory will aid that outcome, making sure it is a worthwhile venture.

Respiratory disease

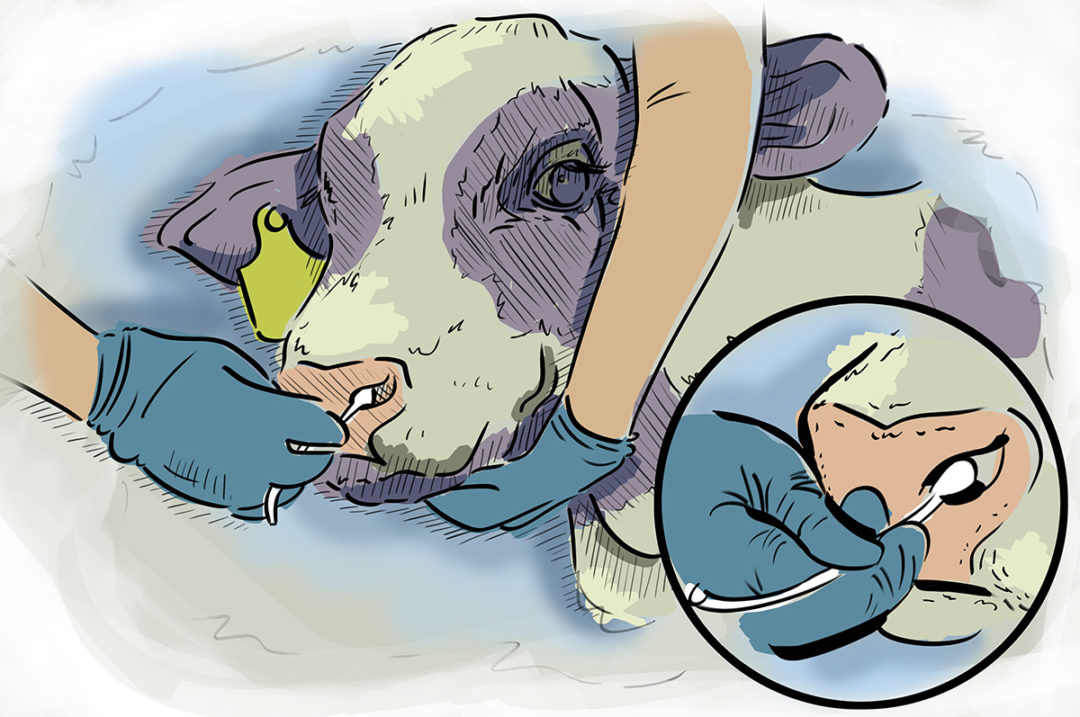

Fortunately, there are techniques to sample live dairy cattle once clinical signs are apparent with the possibility of treatment after diagnostic collection is complete. Nasal swabs and deep nasopharyngeal swabs are two possible methods by which this may be accomplished. The nasal swab is convenient to use by inserting into the nostril of an affected animal and giving a gentle twirl. These specimens are especially good when looking for respiratory viruses; however, their usefulness is limited with respiratory bacteria.

Bacteria can inhabit the nasal passageways of the upper respiratory tract in healthy cattle. Once natural defenses and the immune system become compromised, these organisms can travel down the trachea, or windpipe, and cause damage in the lungs. To better sort out which bacteria are posing a risk, deep nasopharyngeal swabs should be used. These devices have two sheaths or coverings over the swab that are intended to protect against contamination while passing through the nostrils and snouts of the animals. While not as simplistic to operate as a nasal swab, a little training with a herd veterinarian will ensure proficient use.

Once an animal has died, there is even greater potential to work with a veterinarian to diagnose the cause of illness. Lung is submitted in respiratory cases but associated tissues like lymph nodes and trachea are useful as well. Swabs of these tissues may be obtained and sent alongside to the diagnostic laboratory, which will enhance the likelihood of finding the organisms responsible. Collecting and submitting a full tissue set which includes representative samples and swabs from the major organs plus the digestive tract not only helps ensure the entire scope of the disease is detected but may provide additional insight about other subclinical infections.

Pinkeye

Like with respiratory disease, swabs are an important tool for sampling cases of pinkeye. Appropriate timing of sample collection and use of culture or transport media will maximize the yield of information. In this instance also, the key is to swab an affected eye soon after clinical signs first develop, before one organism has time to overgrow other contributors. Early stages are characterized by excessive tear production and mild changes to the eye. A severely reddened eye with a white center and the absence of damp hair below it are indications the disease has already progressed too far to be a good sample candidate. To maintain the viability of pathogens while traveling to the diagnostic facility, the swabs should be placed inside the specialized tubes that often accompany a collection kit.

Takeaways

With an opportunistic mindset and a strategic approach, it is possible to turn the misfortune of disease into a situation that generates value. Infectious organisms will continue to exist and evolve, but a clear understanding of which contributors are present in a herd will allow for development of the most effective remedies. Proper diagnostics will define the challenges and ensure correct solutions are implemented to reduce risk. Following some basic principles will help transform the immediate cost implications into an investment that produces improvements for the betterment of animal health and the overall success of the operation:

- Commit to problem solving through well-conducted diagnostic discovery.

- Select representative animals with early lesions that are a reflection of the group issues.

- Utilize swabs appropriately for capturing disease dynamics in both living and dead tissue.

- Preserve sample quality through careful storage and transport methods.

- Document observations and share information with all participants involved.

- Form an integral relationship with a veterinarian to work collaboratively on disease investigations and intervention strategies.