Let’s play a simple word association game. When I say “milkfat,” what do you say? Palmitic? That’s what I’d expect 80% of you to say if we were having this conversation in person. While palmitic may be top of mind, given the use of palm fatty acid supplements to increase milkfat percent and yield, the making of milkfat in the mammary gland is far more complex than “pulling the palmitic lever.”

In fact, let’s think of the making of milkfat as a blooming onion – deep-fried and splayed wide open to reveal all its yummy layers. While the obvious outside layer may be palmitic, if we peer into the onion’s center we find that making milkfat is, at its core, really about a lesser-known fatty acid called acetate. Making milkfat is truly a story about acetate. My goal in this discussion is simply to review the basics of how milkfat is made and to help the other layers of the onion (particularly acetate) to be top of mind as you manage your herd for more pounds of component-corrected milk.

I am going to start by giving you the answer since I really want this to soak in. Acetate, which comes from the rumen, is the primary driver of base milkfat production. Anything you can do to keep the rumen microbes happy will result in more acetate, thus more milkfat and flow. While palmitic has hogged the limelight in recent years (and it certainly contributes to overall milkfat production), it doesn’t work very well as a Band-Aid to overcome dysfunction in the rumen. Read on to learn the details of the making of milkfat to keep you focused on pulling the right levers for both milkfat and milk flow.

The basics of making milkfat

Before we walk through the mechanics of making milkfat, let me clear the air on some technical fatty-acid jargon. These terms can be confusing even for those of us who work with fatty acids daily.

- Ninety-five percent of milkfat is in triglyceride form. Triglycerides are three individual fatty acids attached to a glycerol backbone (looks like a letter E).

- Fatty acids come in different carbon-chain lengths. Each fatty acid with a different number of carbons has a different name.

- Short- and medium-chain fatty acids are derived solely from the rumen and are sometimes called “de novo” (a Latin phrase that means “made new”) fatty acids (C4-C14).

- The longer-chain fatty acids cannot be made by the cow and therefore must come from the diet. These are called “preformed” fatty acids since they are already formed into longer chains when they are fed (C16-C18 and longer).

- Palmitic (C16) is unique in that roughly half of it comes preformed from the diet, while the other half is synthesized in the mammary gland.

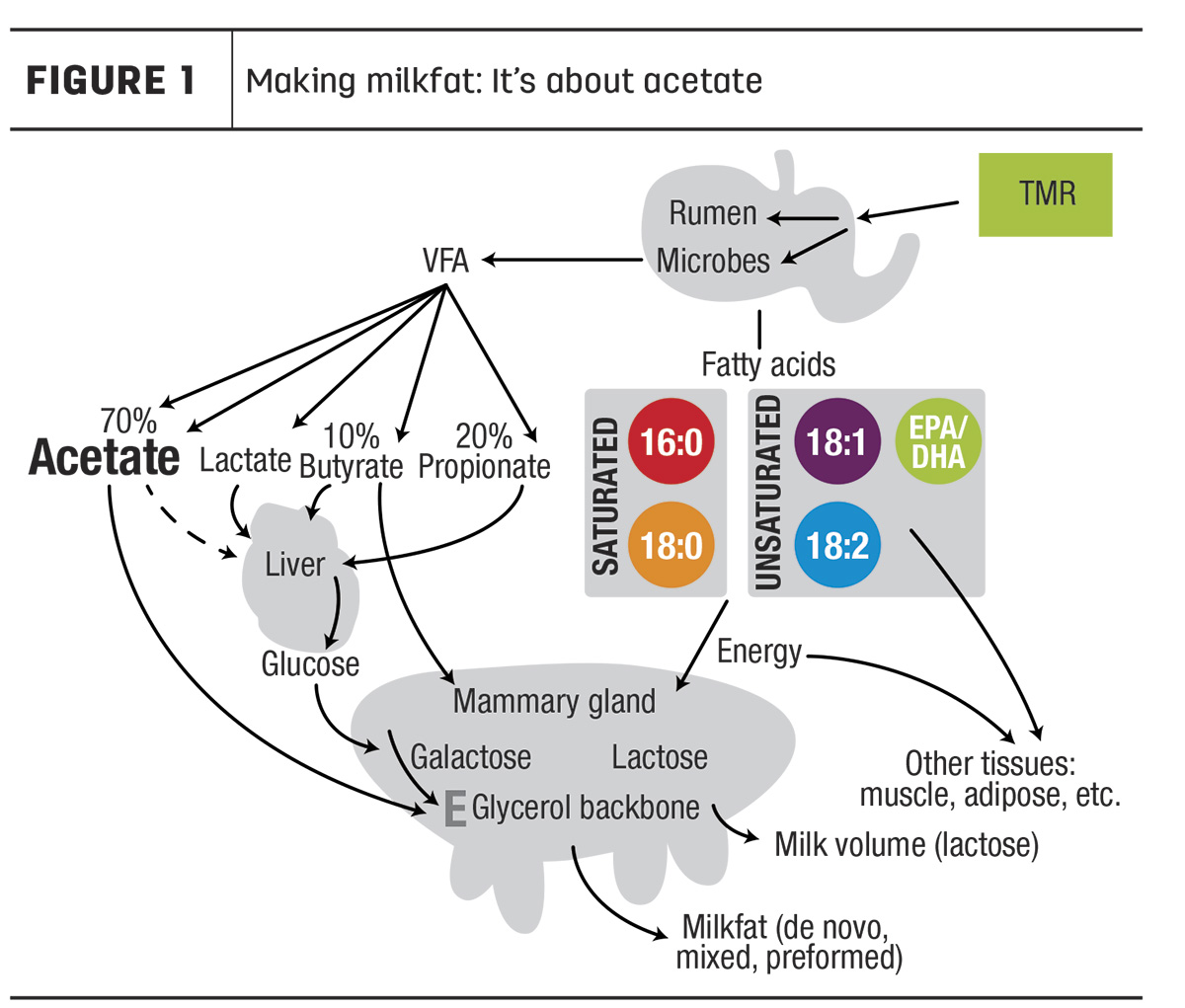

There are two pathways for fatty acids to be transformed into milkfat. They are either derived from the diet or from the rumen (Figure 1). Here are the basic steps in these two pathways.

The rumen-milkfat pathway

Feed consumed by the cow makes its way to the rumen, where the fermentation of carbohydrates by rumen microbes results in the production of volatile fatty acids (VFAs). All three of the main VFAs produced (acetate, butyrate and propionate) are involved in milkfat synthesis.

- Acetate is the heavy hitter, making up 70% of the VFAs in the rumen. This VFA gets directly absorbed into the bloodstream and transported to the mammary gland, where it is then elongated into other fatty acids to make milkfat.

- Butyrate plays a lesser role, accounting for just 10% of the rumen VFAs. It gets transformed into beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHBAs) through the rumen and the liver and then gets transported to the mammary for making milkfat.

- Propionate (20%) is different in that it goes directly to the liver where it gets converted to glucose, galactose and, lastly, lactose. This propionate pathway of conversion to lactose is the energetics behind driving milk volume. Propionate is also highly important in the making of milkfat triglycerides, as it contributes glucose that turns to glycerol, creating the glycerol backbone of milkfat triglycerides.

Roughly 50% of all the milkfat your cows produce comes from these VFAs, with acetate being the primary driver. What can we do to maximize acetate production in the rumen? Take care of those rumen bugs. Feeding high-quality forages, increasing fiber digestibility, feeding a balanced diet, good bunk management and healthy particle size in your total mixed ration (TMR) will all drive better rumen function.

One interesting note on acetate and propionate is that they like to stay in a 4-to-1 balance. If acetate production in the rumen increases, propionate will as well. A true case of the rising tide floating all boats. This means that when you increase milkfat by improving healthy rumen function, you will see milk flow increase as well, with propionate driving more glucose availability.

The feed-milkfat pathway

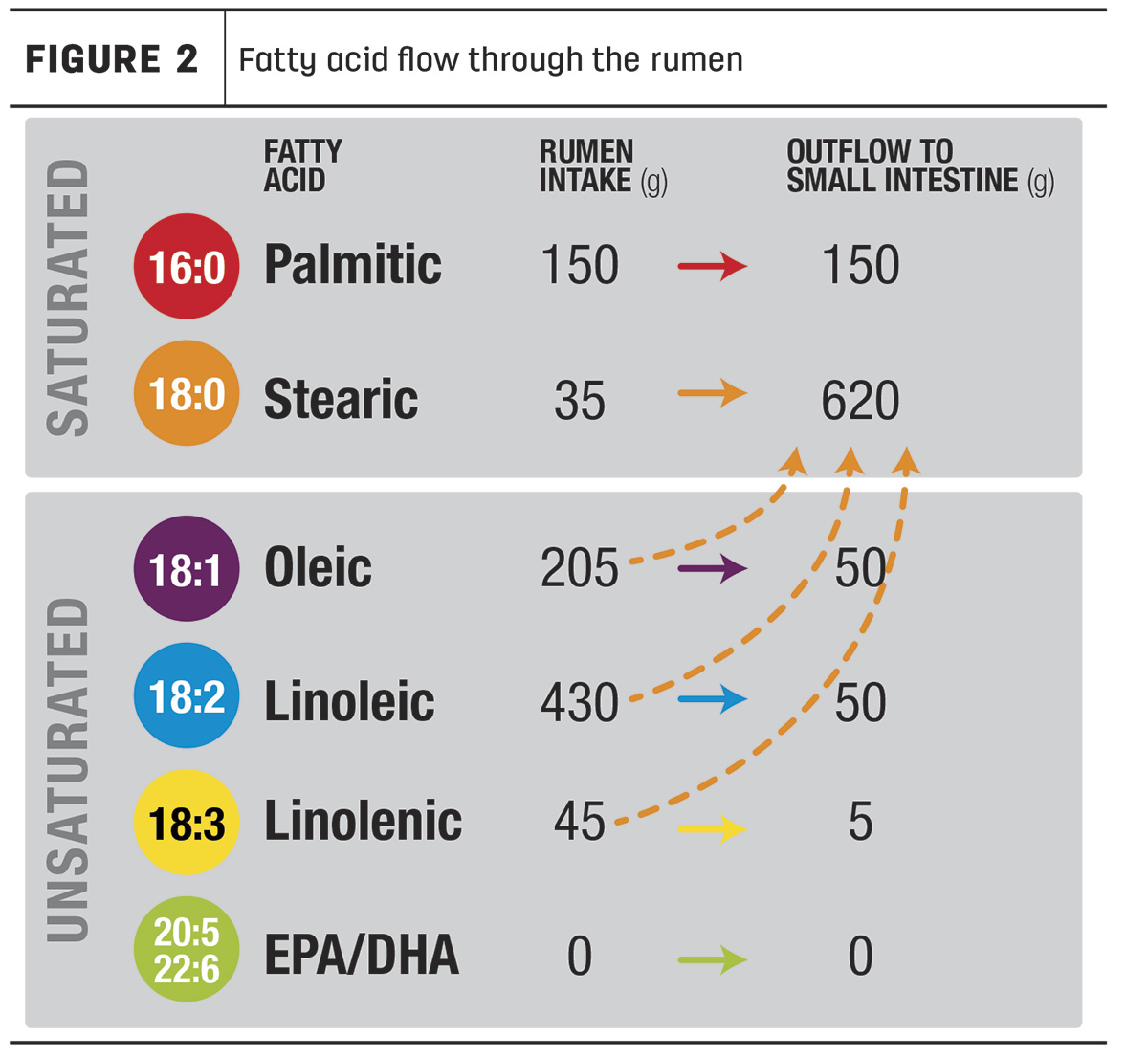

This second pathway for making milkfat is by providing long-chain fatty acids through feed. Some of these fatty acids are saturated (stearic and palmitic), while some are unsaturated (oleic, linoleic and linolenic primarily). The saturated fatty acids go through the rumen to the small intestine for absorption, whereas the unsaturated fatty acids that are unprotected will mostly be transformed by rumen microbes into stearic before making it to the small intestine for absorption (Figure 2).

These long-chain fatty acids that are provided by the diet typically make up around half of the total milkfat the cow produces. Cows are metabolic athletes in that these long-chain fatty acids can also be directly taken up by the tissues for other energy needs, thus sparing more acetate and propionate for milkfat.

Here is where things get a bit trickier with truly balancing fatty acids and one of the many reasons you have a nutritionist.

- For increasing total milkfat through dietary fatty acids, the profile of fatty acids truly drives the ship. Each individual fatty acid plays a different role and needs to be fed in balance.

- How many grams of the individual fatty acids are being fed, and in what form are they being delivered to the rumen (protected versus naked fat), are variable.

- If there are too many unsaturated fatty acids in unprotected form in the rumen, particularly 18:2 – linoleic, milkfat will go down.

- Too many grams of stearic, coupled with low oleic at the small intestine, and digestibility will go down, causing dry matter intake to be elevated and lower feed efficiency.

- If there is too much palmitic versus oleic, you may see an increase in milkfat percent, but you may also see lower milk volume and challenges with early lactation body condition.

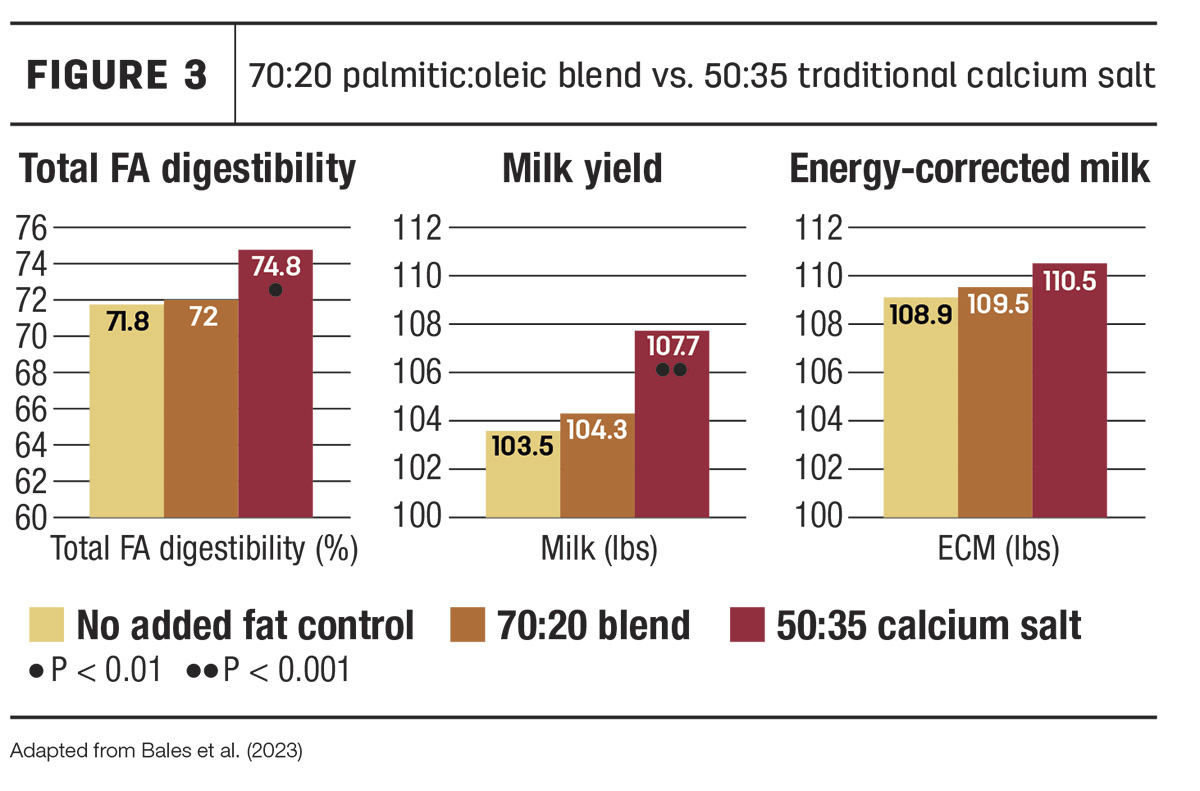

A recent study by Alycia Bales of Michigan State is a good example of this last point and why balance is key. When feeding a higher palmitic to oleic blend (70:20) versus traditional calcium salt (50:35), there are more things going on than simply an increase in milkfat (Figure 3). Milkfat increased as expected. However, the milkfat gains were offset by the traditional calcium salt showing a 3-pound increase in milk flow. The more balanced profile of 50:35 palmitic to oleic in the traditional calcium salt also had higher fatty-acid digestibility, resulting in better overall energy-corrected milk (ECM) and feed efficiency.

Practical tips to remember

Practical tips to remember

While you may not remember every fatty acid by name (as if they were your kids), I do hope you remember these points:

- If you want a blooming onion of milkfat over 4% on your dairy, it starts with making more acetate from a healthy rumen. Help those rumen microbes do what they do best. Take all the forages and byproducts that humans cannot consume and turn them into glorious (and profit-driving) milkfat.

- Fatty acids need to be fed in balance. No one fatty acid (looking at you, palmitic) is going to get you to the pounds of milkfat you desire to reach in the next few years.

- Remember that you get paid on pounds of milkfat and not percent. If we pull too hard on that palmitic lever, the cow will respond with lower de novo synthesis of fatty acids, less acetate and less flow.

Be sure your measuring stick for successful fat supplementation includes all three of these parameters: 1) pounds of fat, 2) pounds of milk/ECM and 3) dry matter intake/efficiency (plus, keep an eagle eye on early lactation body condition).