With the 2024 crop season around the corner, it is time to plan for forage inventory, field management, harvesting and storage.

Considering that forage comprises more than 60% of our dairy diets, even small tweaks to forage management can have a great impact. We talk about starch and fat, but the energy that comes from forage digestible fibre in elevated amounts is often overlooked. Feeding high-quality forage provides energy for the lowest cost. Since cows consume 1% of their bodyweight as forage neutral detergent fibre (NDF), any NDF intake limitation due to low quality, limited availability or environmental factors, increases feed costs and decreases return over feed.

In an average year, first cut represents roughly 50% of the total haylage yield. Quality is greatly affected if weather hinders the harvest. Harvesting first cut at the right maturity and efficiently storing this feedstuff will enable lower feed costs and increased component yield per cow per day.

A look back to move forward

How did we do in 2023? What have the cows told us? And what did chemical analysis reveal?

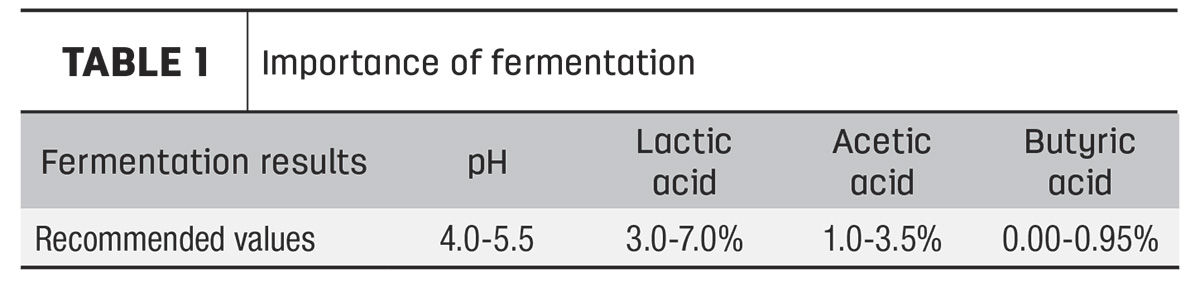

Most laboratories provide a fermentation analysis, which is a good starting point to evaluate your feedstuff. Depending on the legume content, we target a pH between 4.4% and 5% for haylage with a lactic acid, an acetic acid ratio close to 3-to-1 and a butyric acid content as low as possible (Table 1).

Parameters that highlight successes from 2023 and show opportunities for 2024 include:

- Protein – The level of crude protein in the forage decreases as maturity increases, generally greater in legume forages.

- Available protein – Crude protein minus the amount of protein that is bound to the acid detergent fibre (ADF) fraction of the forage. This protein is unavailable to the cow and may be a sign of heating during the storage process or at feedout.

- NDF and digested NDF (dNDF) – NDF represents the thickness of the cellular wall. For a mature plant, the thickness of the cellular wall increases, decreasing the digestibility. Therefore, we aim to balance the level of fibre NDF and the digestibility of this fibre to feed the rumen.

- Ash – Consists of minerals; forages that have a lot of dirt contamination will have higher-than-normal ash, which can lead to poor fermentation. Ash content should be below 10%, on average. For forages with an ash level above 10%, there is a decrease in residual sugars.

Timing is everything

When it comes to forage production, the first cut timing sets the tone for the season. Grass stands should be cut at early bloom. While cutting alfalfa stands is dependent on many factors including concentration within final diet, we generally target 1% to 15% flower. The percent of flower is an old method providing a great visual; however, it is inaccurate when it comes to plant maturity. A better option is to check the height of the alfalfa plant. A 100% alfalfa field should be cut when the majority of plants reach 30 inches. When the field is 50-50 alfalfa-grass, the recommended height is 24 inches, and for a purely grass stand, reference a nearby alfalfa stand: Once that alfalfa reaches 15 inches, your grass stand is ready to cut. Cut height needs to be a minimum of 4 inches to avoid dirt contamination.

Length matters

Haylage should be chopped at 3/8-inch to 1/2-inch theoretical chop length.

Use the Penn State Shaker Box or the length of chop analyzer established with your feed adviser during harvest as a quick spot check to ensure the right length before feed is stored. When it comes to the Penn State Shaker Box, we suggest 5% to 15% on the first pan (as close to 5% as possible) and 65% in the top two pans combined.

Too wet or too dry – that is the question

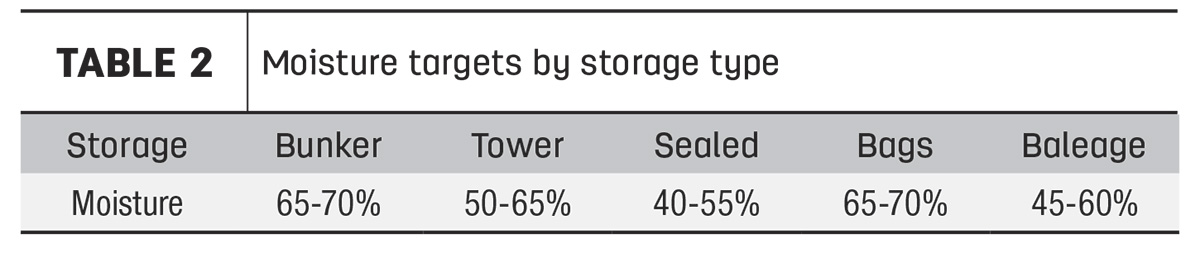

Ideal forage moisture enables good compaction and in turn optimizes fermentation. Forage that is too wet will have a greater acetic acid content, leading to lower forage intakes, while forage that is too dry will make the feedstuff difficult to compact, disrupting and prolonging the fermentation process (pH remains elevated) and decreasing feedout stability (heating at feedout). Ideal dry matter is 32% to 38%, which provides enough moisture to improve microorganism growth while limiting clostridia bacteria growth. A word of caution: Some tower silos perform poorly with a dry matter percent that low, while most work well between 35% and 45% dry matter (see Table 2 for moisture targets by storage type).

Inoculant

Use an inoculant that contains lactic acid bacteria to produce lactic acid. This will help speed up fermentation while reducing nutrient and dry matter loss. Buchneri inoculants take lactic acid and convert it to acetic acid to increase bunk life, but they do not improve fermentation. Propionic acid preservatives similarly do not improve fermentation but limit the growth of yeasts and moulds and increase bunk life. These preservatives can be especially helpful with poor compaction (for example, top of silo) and when the moisture content is outside the recommended range.

- Lactic acid – Lactic acid is the primary product of fermentation. It is the strongest acid and uses 10 times less rumen fuel to get to terminal silage pH.

- Acetic acid – A weaker acid that uses up more rumen fuel to get to terminal silage pH. It should always be lower than lactic acid.

- Butyric acid – The result of clostridial and/or bacillus fermentations, which results in decreased nutritive value, decreased intake and may increase the incidence of ketosis.

Inoculant application is important because haylage has varying buffer capacities. Buffer capacity is the capacity of the forages to stay at a pH of 7. Powerful acids are needed to drop the pH when the buffering capacity in silage is high. This capacity drops with forage maturity. To achieve forage quality, low to medium forage maturity is recommended. Buffering capacity also increases in forages grown in well-fertilized soils, which are often favoured due to their positive impact on yields and quality. Finally, ash and legumes increase buffering capacity compared to grassy, low-ash forages. Accounting for the buffering capacity, some inoculants help drop pH more quickly.

Pack, pack, pack

Proper compaction creates an oxygen-free environment for anaerobic bacteria to thrive and to produce favourable acids (lactic acid), which will drop the pH and stabilize feedstuff. Oxygen will have a detrimental effect on good bacteria, in turn leading to a higher pH for an extended time, allowing bad bacteria, yeasts and moulds to proliferate and consume valuable nutrients. One of these nutrients is sugar, an excellent source of carbohydrates. Another negative effect of an extended fermentation is heat. Elevated heat will bind protein and lead to lower available protein.

For compaction, we aim to achieve a bunk density greater than 15 pounds per cubic foot (240 kilograms per cubic metre). To meet this target, layers of new forage should be no more than 6 inches thick; layers greater than 6 inches will lead to lower compaction for equivalent tractor weight.

When working with a bagger, it is important to respect the plastic capacity, which is indicated on every bag. Adjust pressure to respect the limits of the bag itself. For bunkers and piles, you need weight; the greater the tons per hour arriving at the bunk, the more weight is needed.

Forage first cut will influence subsequent cuts and forage season success in 2024. Evaluate 2023 forage performance to identify opportunities for cut times, cut length, moisture, inoculant usage and compaction. Optimizing feedstuff quality that enters the silo or bunk will ensure a rapid fermentation process with less nutrient loss, better feedout stability, and greater intakes and energy for your herd.