Feed costs account for more than 45% of production costs and approach nearly 60% with high feed costs. Obviously, dairy income is directly proportional to milk volume, composition and quality produced on the farm. Highest milk yield does not always equate to best farm profitability. A balance needs to be determined here, and it all hinges on how well you feed the cow and her rumen microbes.

The published consensus report by the National Research Council (NRC), now named the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM), provides us with the best “guiderails” in feeding dairy cows.

The eighth edition of this publication was released in December 2021. The previous edition had been released in 2001. Just consider what has happened in these 20 years to dairy cow genetics, management, research and productivity. It would seem the committee faced a daunting task to compile, evaluate, debate and finally generate feeding guidelines.

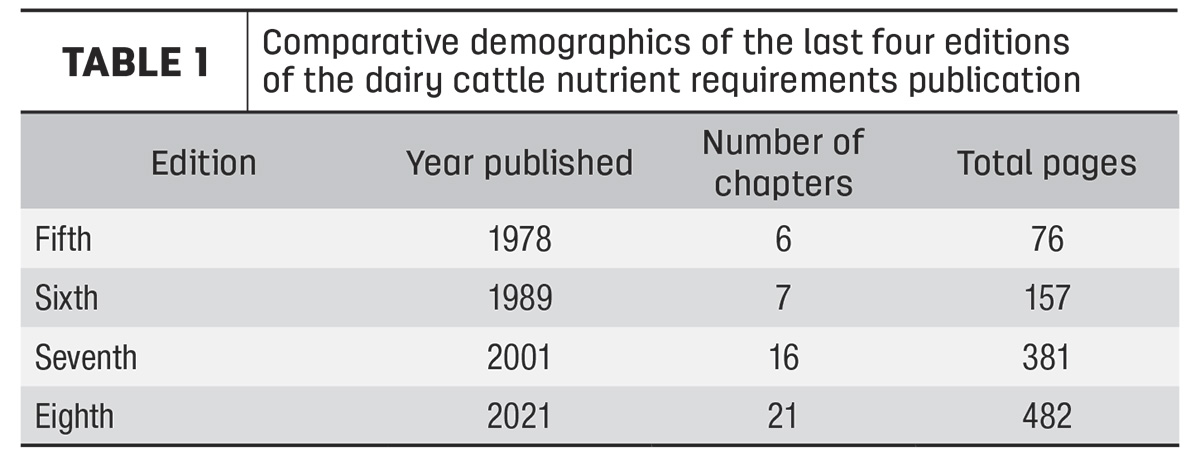

To give you some impression of our continued understanding and complexity of dairy cow nutrition, consider the number of pages in the last four editions (Table 1). As you might expect, the typeset is much smaller in the latest edition, so on an equal basis may be even longer.

Why such differences? We have come a long way in understanding rumen microbial function and nutrition, which has greatly influenced how we should be feeding the cow. Research continues to refine our ability to model and predict rumen fermentation outflow to support the cow’s needs. One of the changes seen in the new report is how the science has moved further along in describing dietary ingredient components relative to their degradability in the rumen.

Dietary fiber

One example here is the introduction of physically adjusted neutral detergent fiber (paNDF) as it affects rumen health. Spanning the years of these dairy cattle requirement publications, we have seen assessment dietary fiber, a critical component of the diet for rumen health and function, change from crude fiber to neutral detergent fiber to effective (eNDF) then physically effective NDF (peNDF) and finally rumen degradability.

The paNDF system is based on maintaining a rumen pH of 6.0 or 6.1, which is necessary for efficient fiber digestion. This modeling system accounts for the interaction of forage NDF, fiber fragility, particle size and dietary starch content. This sounds quite complicated, and the model equations certainly are. However, your nutritionist can input the appropriate parameters of cow bodyweight, dietary forage NDF and starch content, then use the Penn State Particle Separator to determine the amount of material on the top (19-millimeter) sieve. With this information, the model will determine the amount of material needed to be on the second (7.9-millimeter) sieve to maintain the desired rumen pH. The only complication for on-farm use is that the material on the sieves must be in dry matter, but this could also be completed on the farm.

Energy and protein

Other important modifications include improvements in energy and protein requirements.

From an energy perspective, the maintenance net energy of lactation (NEL) requirement was increased 25%. In conjunction with the change in energy needs, the consensus report has modified the calculation of energy within feeds to account for sources of variation. In contrast to the 2001 edition, non-fiber carbohydrates (NFC) were separated into starch and residual organic matter (ROM; namely, neutral detergent soluble fiber and water-soluble carbohydrates). This separation allows for addressing differences in starch degradability whereas the ROM was defined as at 96% digestible. Supplemental dietary fatty acid digestibility was reduced from 92% to 73%. Digestibilities of both NDF and starch are reduced based on dry matter intake (DMI), but to a lesser extent than described in the previous NRC edition. These changes will improve our ability to predict dietary impacts on cow energy balance.

Relative to cow protein requirements, the report has taken a new direction, moving away from calculating protein requirements based on metabolizable protein (MP) but focuses more on delivery and utilization of essential amino acids (EAA). This was quite an undertaking literature review process to define EAA needs for all proteins synthesized by the cow. These proteins include those lost in milk, urine, scurf and feces (defined as secretions) and protein gains such as tissue growth and pregnancy. From here, the efficiency by which dietary EAA are used to meet these protein needs was determined using a variable efficiency depending upon the protein synthesized. Ultimately, this new approach to protein nutrition should allow nutritionists to formulate diets for lower protein content and maintain good performance. This will help reduce feed costs as well as address environmental concerns with excess nitrogen.

Transition cow feeding

There has been much interest in feeding and management of the transition cow, as the period following calving is often fraught with greater disease risks. The NASEM 2021 report has moved to a continuous function in predicting energy and protein needs of gestation, which is physiologic but makes for some challenges in meeting requirements with one or two different diets. Predicted DMI during the dry period has been modified to account for dietary NDF content. As dietary NDF increases from 30% to 50%, DMI will decline.

Dietary vitamin E content has been increased from 1,000 IU per day to 2,000 IU per day for the close-up dry diet. Trace mineral needs were also increased for the dry cow with minimal changes for heifers and lactating cows.

Minerals and vitamins

In addition to some changes in mineral and vitamin requirements, the new NASEM report provides more detailed information on bioavailability of minerals from various feed ingredient sources. A more significant change here is the different perspective on defining essential nutrient requirements provided in the report. Previous NRC publications defined requirements on published studies using a specific production outcome as a response. In the 2001 report, some requirements, such as vitamins A and E, were modified based on disease prevention studies.

A factorial approach was used as in the past, but the NASEM committee did not define the “requirement” but used data to generate a population mean value. Ideally, if the data were sufficient to calculate the nutrient variation, a safety factor was used. However, few nutrients had sufficient data and thus the committee provides a recommended “adequate intake (AI)” in place of a “requirement.” What this means is that the consensus committee believes if you fed the defined amount of trace mineral or vitamins, it would meet the needs of most cows, thus leaving much room for adjustment.

There is much more information provided in this detailed report. Fortunately, there is a computer software package available free of charge on the National Academy Press website that does the calculations and comparisons. The program was designed to be very similar to the previous software so should facilitate a shorter learning curve.