The foundation of most diets fed to dairy and beef cattle includes forages, but making them into high-quality silage that can be fed year-round is a challenge. Considerations must be made for storage structures, equipment, plant characteristics, chop length, use of additives and more. Generally, the silage production process can be split into four phases. This includes the aerobic phase, fermentation phase, storage phase and feedout phase. Proper silage management should begin well before the feedout phase, as the material you put into your silo will need to be of superior quality in order to be a valuable end product.

Storage structures and equipment

Before beginning to harvest forages, ensure all storage structures and equipment are in good working condition. Clean out any old feed from your silos and thoroughly inspect for any cracks or damage to its structural integrity. Make sure to patch any holes that would allow oxygen to enter the silo. If you plan to use a vertical silo, also check the door seals, ladders and cages. If your silo is older than 10 years, consider having a professional inspect it.

Change oil, filters and lubricate parts according to the owner’s manual for equipment. Inspect hydraulic hoses and replace any worn gears, belts, bushings, sprockets and chains. Order spare parts to try to avoid any delays if a piece of equipment breaks midharvest. Most importantly, make sure to sharpen or replace knives on the cutter head. Dull knives tend to tear forages, which decreases the accuracy of the cut, making it harder to pack properly and less digestible to the animal. Additionally, dull knives can tear the plant cell, leading to seepage and further nutrient loss.

Dry matter and maturity

In order to get the most from your crop, it is important to harvest at the correct dry matter and maturity for that specific plant variety. For corn, the whole-plant dry matter is a better indicator of quality versus the stage of maturity. You should target to harvest corn with a dry matter of around 32% to 35%. As the corn plant matures, lignin and prolamins increase, which decreases fiber and starch digestibility, respectively.

For hay and small-grain silages, the stage of maturity is more important since the plant will be wilted to the desired dry matter before ensiling. The following stages of growth should be the target for the time of harvest: alfalfa in the bud to early bloom stage, grasses in the boot stage and small grains in the boot to soft dough stage. Oftentimes, a compromise has to be made between when the plant is most digestible at an immature stage and when yields are highest when the plant is very mature. Once cut, alfalfa, grasses and small grains should be wilted to a dry matter of around 35% to 45%.

It is important to test the dry matter regularly before and during harvest. Tools you can use include a Koster tester, microwave or electronic tester. A Koster tester and microwave are more accurate, as they measure the dry matter by using the difference in weight before and after physically drying the plant material down. An electronic tester works by measuring the electronic conductivity of the forage and can be useful for several quick measurements at different points. However, they need to be calibrated and often are not as accurate.

Chop length and particle size

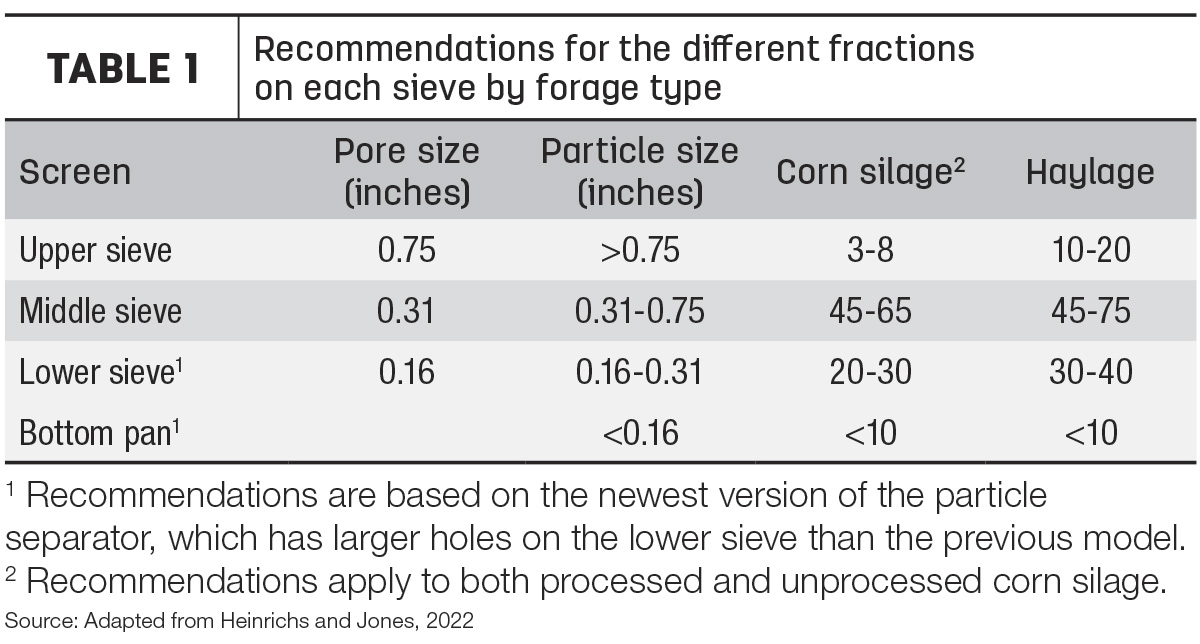

The chop length for forage being made into silage should be evaluated before and during harvest to make adjustments if needed. Chopping forage too long will make it more difficult to compact, easier for cattle to sort against and harder to digest. Inversely, forage that is chopped too short will not be a good source of physically effective fiber. The recommended chop length is three-eighths to three-quarters of an inch for corn silage and three-eighths to half of an inch for alfalfa haylage. The particle distribution can be measured using a Penn State Particle Separator. Recommendations for the different fractions on each sieve depending on forage type are listed in Table 1.

Storage

Once harvest has begun, try to fill the silo quickly, pack it well to exclude oxygen, and cover it immediately. If packing in a bunker or drive-over pile, pack in layers approximately 6 inches thick using the progressive wedge technique. It is important to exclude oxygen from the forage mass in order to deter the growth of undesirable microorganisms such as yeasts and molds. The recommended packing density is 15 to 16 pounds per cubic foot on a dry matter basis and 44 to 48 pounds per cubic foot on a wet basis.

Once the silo is filled, cover it immediately to further prevent oxygen from entering the silo. Choose an oxygen-limiting barrier and plastic that is at least 6 mil thick. When packing silage in a bunker or trench silo, cover the walls with oxygen-barrier plastic in addition to the top. Also use sandbags, tires or other means to weigh down the plastic to further prevent oxygen from entering the forage mass.

Additives

During the fermentation phase, various byproducts, mainly lactic acid, are produced that aid in preserving the forage for year-round use. In order to drive fermentation in a desirable direction, consider the use of a silage additive. Generally, silage additives can be broken down into three main categories: chemical additives, microbial inoculants and enzymes. The decision to use any of these additives may change depending on the growing and harvest conditions of the crop.

They generally aid in decreasing the pH faster, inhibiting the growth of undesirable microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, increasing aerobic stability during feedout and helping to better preserve nutrients. Think of silage additives as an insurance policy to protect your investment in your forage.

In addition to the quality control points listed above while making silage, make sure to maintain quality during feedout. This includes maintaining the face by removing silage in even layers using a defacer or unloader. Cut plastic back at the same rate at which material is being removed from the silo for bunk and drive-over piles. This should minimize the surface area exposed to oxygen and other elements.

Overall, it is imperative to manage your silage well in order to provide a high-quality feed product to your animals. Good management starts in the field before the crop is even harvested. Forage forms the foundation of the ration, and without a strong foundation, it is hard to recover.