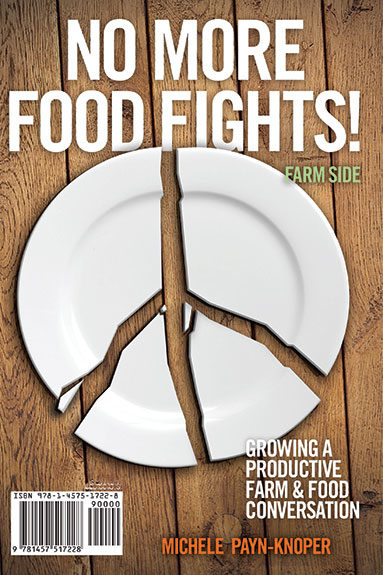

In the social media realm, Michele Payn-Knoper of Cause Matters Corp. is regarded as an expert of all things “agvocate.” She has spent more than a decade as a professional speaker training farmers and ranchers on promoting the agricultural industry through tools like Facebook and Twitter and growing relationships with consumers. In her new book, No More Food Fights!, which was released Feb. 14, 2013, Payn-Knoper could have written directly to foodies, educating them on the many aspects of the agriculture industry today.

Or she could have spoken directly to her core audience of farmers and ranchers, providing them with key messages to hammer the “right” points into consumers’ minds.

Instead, Payn-Knoper allows many voices to get the true point across: It’s time to open up the dialogue about food production.

The book is written with a farm side, written for farmers and ranchers – and by flipping the book over, readers see the other half of the book, directed at consumers and foodies.

There’s an identical chapter in the middle for both sides, written specifically to bring both sides of the plate together.

I remember having a discussion with Payn-Knoper after attending one of her advocate training sessions about a year ago. We were talking specifically about the dairy industry’s involvement in social media.

I asked her, “It seems like there’s a lot of dairy industry people involved in social media now. How do we make sure we’re all saying the same thing?”

What this book made me realize is that we shouldn’t be this large army of drones, all spewing out the canned answers about milk quality and animal care. Is it important to know those key messages?

Absolutely. But as Michele and I discussed during our “3 open minutes” interview [ Click here to view interview], it’s more important to personalize those messages and tailor them to each individual conversation you engage in.

On the food side, Payn-Knoper introduces several farmer voices from all sectors of agriculture and allows them to explain what they’re doing on the farms and why they’re doing it. Along the way, she provides “rotten vegetables”: areas that typically halt a productive discussion about food in their tracks.

Examples on both sides include the type of language used. Words like “factory farms” and “big agriculture” come across as accusatory to farmers and put them on the defense.

Similarly, phrases the general consumer may not completely understand, such as “GMOs,” may scare them off and put an end to what could have been an opportunity to talk about progress on farms today.

Payn-Knoper also provides “connection points,” or areas that will help and not hinder the conversation between consumer and farmer.

On the farm side, she introduces several consumer voices to share their viewpoints on the ag industry and what aspects they’d like to know more about.

The most interesting section of the farm side of the book for me was reading about Chef Renee Kelly of Kansas. She’s created a dining experience for her customers based mostly on products from local and regional farmers.

Payn-Knoper writes that while Kelly “loves the idea of buying from her neighbor,” she’s also realistic about the fact that large farms are needed too.

When asked to delve deeper into her concerns with large farms, Kelly used a teacher-student ratio as an example: “In a classroom with 15 kids, you are a better teacher and give students individual attention. If that’s tripled, you can’t possibly give the same attention to each child. That doesn’t mean the teacher suddenly becomes a horrible teacher or a bad person. The same is true for farms.”

It’s a unique perspective, and one I never thought about or heard from anyone else, including animal rights groups who I thought had cornered the market on analogies of animal care. Kelly certainly doesn’t think all large farms are “bad.” She just feels that smaller farms can provide more individualized attention.

If I were having this conversation with Kelly, I could point out several large farms who also do a great job with individualized attention. They are capitalized enough to provide cows hourly attention through the use of new technology and strategically deployed, well-trained employees.

Payn-Knoper immediately follows up this section about Kelly’s views on farmers by going into how to develop connections by identifying “hot buttons”: their interests or passions.

By being willing to get to know Kelly and hear about her previous experiences, Payn-Knoper could identify that where food is grown is Kelly’s hot button. Finding common ground there allowed Kelly to share her viewpoints rather than putting her on the defensive about her choice to work with small, local farms.

Payn-Knoper said before writing the food side of her book, she talked with Kelly and several others on the other side of the food plate: “foodies,” dietitians and her own network of fellow mothers and professional speakers.

She first listened to the questions they wanted answered and the concerns they had about food production. She then wrote that section of the book to help answer those questions and provide ways they could seek out information.

I think that’s what we all need to do in our everyday interactions with consumers, both in person and online: Stop. Listen. Focus on what they’re saying. Then share our experiences.

It’s not always easy. In the identical chapter, Payn-Knoper talks about some of the qualities those on both sides of the plate need to have, including passion, optimism and an open mind.

She ends the book by encouraging readers to use their silverware to help them remember tips for reaching across the food plate. The fork represents a stake in the ground; use it to help you remember to find common ground and similar interests.

Spoons serve as a reminder to warm the relationship. Make an effort to understand the person’s viewpoints, even when they’re the opposite of yours. Knives symbolize leverage. Influence others around you and build a community to help share stories of farming. PD

Emily Caldwell

Editor

Progressive Dairyman