The act of storing solid and liquid manure does alter the composition of manure from its raw state and could be consider a form of treatment on the manure. However, as dairy farms have altered the way they handle manure from simply storing it, soil scientists are looking into how those newer methods are affecting nitrogen and phosphorus in the end product. Speaking at the North American Manure Expo in Prairie du Sac, Wisconsin, last month, Chris Baxter, associate professor of soil & crop science, University of Wisconsin – Platteville, explained the three types of manure treatment systems that were considered include liquid/solid separation, anaerobic digestion and composting.

Liquid/solid separation removes large particles that are high in carbon and low in nitrogen. This decreases the total carbon in the liquid, which should be noted is not completely void of solid particles. It has been found that phosphorus separates with the small solids.

In anaerobic digestion some of the nitrogen and phosphorus compounds are converted from an organic state to the more available inorganic forms. However, this process can be affected with the addition of off-farm substrates to the digester.

Nutrient changes in composting vary based on the type of composting system used, Baxter said.

To evaluate the nitrogen availability of treated manure, Carrie Laboski (pictured at right) , associate professor of soil science, University of Wisconsin â Madison, performed a study in a lab environment using five agricultural soil types.

Twenty dairy manures were collected from five farms. Two of the dairies had anaerobic digesters with liquid/solid separation. One farm had liquid/solid separation only. Another farm had managed compost, while the final dairy had bedded pack compost.

In all but one instance, the manure was applied to the soil samples at a rate equivalent to 300 pounds per acre, or 120 pounds per acre of nitrogen.

One liquid manure sample had to be applied at 200 pounds per acre because any more would have overly saturated the soil sample. Once applied, 16 weeks were allowed for incubation.

According to Laboski, manure treatment can have a significant difference on the short-term potential availability of nitrogen.

She found that separated and digested liquids have more potentially available nitrogen (PAN) than raw manure, whereas separated and composted solids have less PAN than raw manure. She also learned that some solid manures can lead to nitrogen immobilization in the soil.

However, she mentioned this was done in a laboratory setting and she would like to perform a similar study in a field setting.

In a field study, performed by Laboski in 2005 to evaluate manure phosphorus availability to crop growth, she found the dairy slurry had significantly greater yield than fertilizer applied at the same rate as total phosphorus.

All other manure types (dairy semi-solid, swine and poultry) were equivalent to fertilizer.

A third study on soil phosphorus was performed in a laboratory setting. It used five soils and 18 dairy manures from five farms with a 10-week incubation. Here it was found that the manure phosphorus buffer capacity was generally greater than fertilizer. However the data was only significant in less than 30 percent of the comparisons.

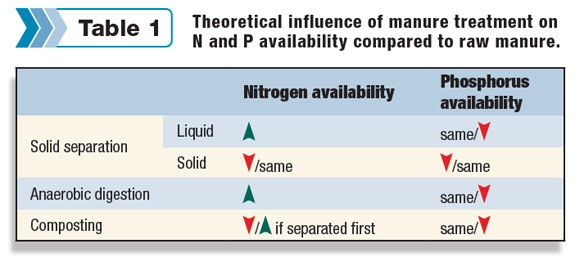

Based on research thus far, Baxter and Laboski created a theoretical table outlining the influence of manure treatment on nitrogen and phosphorus availability compared to raw manure. See Table 1 .

In terms of nitrogen availability, it was increased for liquid effluent from separation, digested manures and composted manure (only if it was separated first). Nitrogen availability was decreased for composted manure and the solid portion after separation.

For all three types of treatment, phosphorus availability either remained the same or decreased. PD

Photo by Karen Lee.

Karen Lee

Editor

Progressive Dairyman magazine