For some time, anaerobic digesters for nutrient management and clean energy have been discussed and utilized. However, much of the dairy industry is still unfamiliar with these beneficial systems.

Sometimes referred to as biogas systems, digesters process organic material into both renewable energy and recycled solids in anaerobic digestion, similar to how a cow’s rumen works. Essentially, the energy in the forms of carbon, hydrogen and methane are extracted, leaving behind nutrient-dense solids and fibrous material. The rise of more available and affordable technology along with the industry’s principles of sustainability, economics and efficiency are strong indicators this technology has a place in dairy’s future.

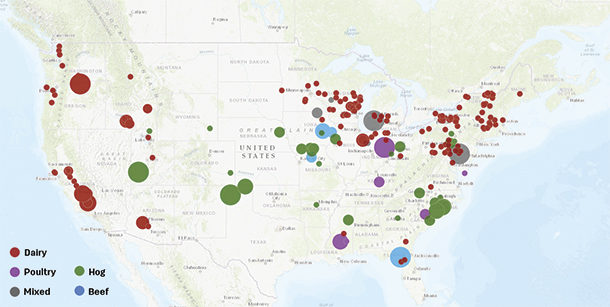

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions and safe, efficient manure management are efforts shared by livestock producers and environmentalists. Anaerobic digesters are a solution to both these, plus they have plenty of additional benefits for farm businesses and communities alike. The opportunity to implement such systems is impressive. The EPA AgSTAR Program estimates over 8,000 U.S. dairy and hog operations can support biogas systems, but currently only about 250 do.

Full of potential

“Anaerobic digester systems are a key tool for sustainable manure management. They can create additional value from an already valuable resource: manure,” says Nicholas Elger, who has managed the EPA’s AgSTAR Program for five years. “From an environmental perspective, they can reduce air pollution by capturing methane gas that would otherwise be emitted into the atmosphere.”

Additional benefits include odor reduction and enhanced nutrient management, as manure run through digester systems can be applied at more precise rates, reducing runoff potential. Pathogens are also destroyed in the process, helping further preserve water quality.

Economically speaking, Elger explains that digesters can diversify revenue for farmers in a variety of ways. The first and most commonly known is clean energy production – biogases captured in the system can be used for electricity, thermal or natural gas applications either on the farm or sold externally. Costs may also be reduced through the use or sale of recycled bedding and fertilizer. In fact, the use of digested manure as a fertilizer has been known to increase crop production by 10% to 30%.

Another way is through fees from taking in food waste from restaurants and food production facilities, which can also be run through the system. In fact, emerging food waste diversion and nutrient control rules in some regions support the implementation of digesters. Dairies are at a particular advantage, often being in relatively close proximity to processing facilities. Wastewater from whey in yogurt making is one ideal feedstock for these systems, along with other high-energy food byproducts. Besides some revenue, this gives more fuel to the digester to produce electricity or clean biogas fuels for on-farm use or sales.

“In times of low commodity prices, digester systems can help balance the economics of their business and help farmers maintain economic sustainability,” Elger says.

Incentives and adoption

Biogas digesters are a significant capital investment, making it very difficult for individual producers and farms to invest on their own. The American Biogas Council represents the U.S. biogas industry and works to make it easier for farms and businesses to be able to install systems affordably.

“I think it all hinges on how fast a farmer can make a return on his or her investment and how much the farmer wants to manage a renewable energy system in addition to the other responsibilities he or she has on the farm,” says the council’s director, Patrick Serfass.

Serfass says the longer it takes to make a return on investment, the more difficult it is for farms wanting to install systems. Typically, it may be a five- to 10-year return on investment. However, there are several additional benefits and opportunities for additional revenue that can accelerate this in various situations. Systems that create biofuels, for example, can have a very quick return on investment under the Federal Renewable Fuel Standard program.

There are various types of digesters that can work for operations of all sizes and needs, from smaller herds all the way up to very large, in a way that is most affordable to them. Serfass points out that a manure-only digester system typically needs about 500 lactating cows to turn a profit. But smaller operations can find revenue with systems that also take food waste and other organic materials.

“More and more, we’re seeing business models where the cost of capital is spread among two or more entities, which can help spread the risk of the project while also spreading the reward,” Elger states. “Economic incentives such as the California Low Carbon Fuel Standard, Renewable Energy Credits, tax credits and low-interest loans are a great benefit to these projects and encourage additional investment.”

He notes AgSTAR’s goal is specifically to help reduce the risk of developing such projects to help reduce the cost of capital. In addition to the tools and resources they provide, ideas such as cost-sharing can help reduce the cost among farms or other organizations, utilities, cooperatives and even consumers.

Working through obstacles

For all their benefits and versatility, there are still issues to be worked through in making digesters more mainstream in dairy and associated industries.

“I think the biggest issue is really just lack of awareness,” Serfass says. “It’s one of those things where if you’re a farmer and you don’t have a neighbor [who] has a digester [who] you can talk to. I think there’s just a lack of understanding about the benefits and what it takes to operate a biogas system.”

Other barriers include utility interconnection, which can be very time-consuming and costly. While the systems are capable of producing energy uninterrupted 24-7, they are still living microbiome systems. The agitators need to be continually running to ensure the bacteria don’t die.

Some states and utilities in support of digesters and the benefits they provide have already created policies to fill this need, but Elger says more work is needed.

“Farmers are stewards of the land; they want to maintain healthy soils and water for future generations. It’s their livelihood and their family’s livelihood to do so,” he says. “Farmers are part of the solution, but not all of it. There needs to be more support for farmers [who] want to manage manure sustainably.”

One of the main ways to preserve and create new incentives for industries and their partners to invest in digester systems is education of lawmakers, Serfass says.

“The good news is: There’s hardly anyone out there who learns about the benefits of a biogas system and doesn’t get how enormously wide-reaching the benefits are and how much it would benefit our society if more biogas systems were built to help us recycle organic material,” he says.

More hope is on the horizon. This June, the Moving Forward Act (H.R. 2) was released by the U.S. House of Representatives. This $1.5 trillion proposal aims to utilize infrastructure and innovation in rebuilding communities with several tax provisions allowing more opportunities within the biogas industry.

AgSTAR and the American Biogas Council are full of resources for farmers to learn more about digester systems and get in touch with other dairy producers using them.