U.S. consumers are increasingly interested in how their food is produced. Understanding consumer preferences and the choices they are making can help dairy producers, and the industry in general, understand consumer demand for production practices.

It is important to note here the issue is not that the end product differs in quality or content but that the manner in which it is produced, certified and labeled differs.

Cheese is the largest use of milk in the U.S. and drives farm milk prices, making the demand for cheese of paramount importance to dairy farmers. You may have noticed a number of labels on cheese including rbST-free, antibiotic free and animal welfare certified.

How much are these production claims worth to U.S. consumers? One way to get at these values is to survey U.S. consumers to determine their “willingness to pay” (WTP) for production practices. WTP is a measure of demand – higher WTP indicates more demand. In a recent publication, we studied cheese consumption and WTP for animal welfare-related production practices in dairy cattle when purchasing cheese. We used a nationally representative survey of U.S. residents to evaluate their cheese preferences.

While there are many topics related to milk-production practices, this research focused on pasture access, antibiotic use and dehorning. We understand consumers likely have little or no experience with modern milk-production practices. However, these are the people making food purchasing decisions and, as such, their perceptions and preferences drive demand. Looking at the finished product at the grocery store, there are no visible indicators that would tell a consumer how that animal was raised without certified labeling. Consumers need verifiers, such as the USDA or other groups like retailers, to confirm the production practices used, and some may be more trusted by consumers than others. Historically, the USDA has been highly trusted by consumers in verifying production attributes.

Results revealed respondents were willing to pay a positive amount for prohibiting antibiotic use for cheddar cheese for all verifiers studied, which included the USDA, retailer or industry. People were also willing to pay a positive amount for requiring pasture access when compared to pasture access not being required. Interestingly, people were willing to pay a positive amount for both dehorning with pain relief and polled cattle when compared to dehorning without pain relief. However, they were not willing to pay more for polled when compared to dehorning with pain relief.

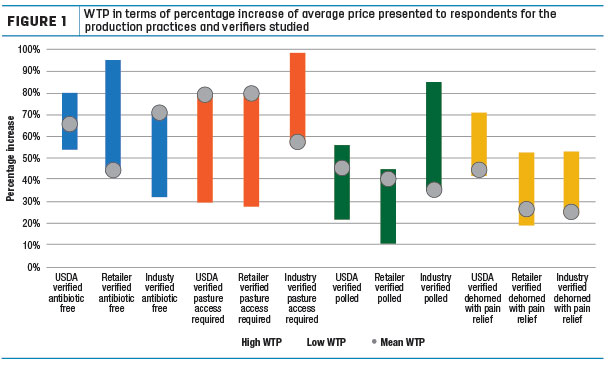

Although actual WTP numbers are obtained from this research, it is important to note respondents were participating in a hypothetical purchasing scenario, which likely inflated the willingness-to-pay estimates. It is difficult for people to internalize the trade-offs they will have to make within their budget when evaluating hypothetical purchases. One of the more important findings for producers is the relative WTP for the different production practices studied. Figure 1 shows the spread of the percentage increase in willingness to pay based on the average price presented to respondents of the experiment.

Taking a deeper dive into the results, it was unsurprising respondents preferred pasture access required over no pasture access required. Everyone enjoys imagining cattle frolicking in lush pastures, and commercials often depict that idealistic environment. Animal science literature presents mixed benefits to such systems, and land and capital restraints may limit the ability of some producers to include pasture access. Evaluating these changes leads to an important consideration regarding willingness to pay estimates. Although some consumers are willing to pay a premium for these production practices, verifiers must be in place for these practices, and labeling must be present to garner a premium.

It is unlikely people are considering the treatment of sick animals when they opt for antibiotic-free production. New research continues to work on this complex problem. People are concerned about antibiotic use for many reasons, including decreases in efficacy and fear of antibiotics being present in consumer products. However, they also are unlikely to want sick animals to suffer. At this point, it is unclear what the answer is in terms of documenting the judicious use of antibiotics, but it is clear that at least some consumers are concerned about antibiotic use.

The use of pain relief in many necessary production practices such as dehorning and castration is not currently a driving issue for U.S. consumers. Other countries already have made changes toward the use of pain relief in agricultural animals. Interestingly, in our study, the use of polled genetics was not preferred over dehorning with pain relief, even though it would mean no dehorning procedure would be necessary. We hypothesize that respondents did not fully understand the implications of polled genetics, or simply preferred anything over dehorning without pain relief. Pain relief is an area where there may be synergy between producers and consumers. There are studies indicating the use of pain relief can increase performance and improve animal recovery, which would have production benefits beyond the ethical questions.

The use of many antibiotics and pain relief medications may require a valid client-patient relationship (VCPR) with a veterinarian, as they are prescription items only. This means a veterinarian must have a working knowledge of the farm and have been on the farm in some capacity in a fairly recent period of time. Rural veterinarians are decreasing in number, and changes in production practices that would require more veterinary intervention could increase the strain on large-animal veterinarians. It is important to consider the level of veterinary support needed for production changes and if that support is available. Establishing a VCPR with a veterinarian will help avoid issues in acquiring prescription products and, in the long run, also provide opportunities for veterinarians and their farmer-clients to discuss other potential methods to improve animal health and welfare.

Note that just because respondents were willing to pay more for these changes in cheddar cheese, this does not mean they are willing to pay for these production changes when purchasing fluid milk, yogurt or other dairy products. Based on consumer research, there is a general preference for dairy cattle welfare and practices that are perceived to improve welfare. While the dairy industry understands all milk is tested multiple times for antibiotic residue and is completely safe, the general public does not. Before considering any production change, producers should evaluate their ability to meet the labor and capital requirements necessary, and ensure that steps are in place to realize and capture any potential premium.

Jonathan R. Townsend is a clinical assistant professor at Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine.