Most ranchers and land managers are familiar with downy brome or cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) and the substantial effects it has on ecosystems – most notably, its influence on fire frequency and intensity.

Two other annual grasses, ventenata (Ventenata dubia) and medusahead (Taeniatherum caput-medusae), also have significant ecosystem impacts, but many people possess limited knowledge about these two interlopers.

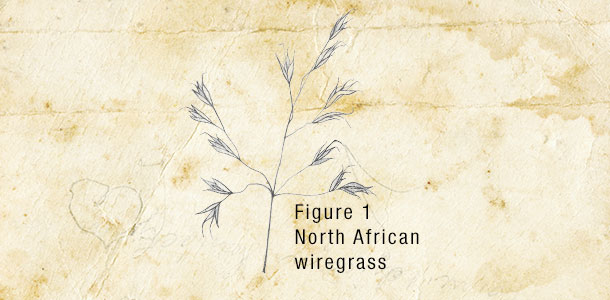

North African wiregrass

(Ventenata dubia)

North African wiregrass (Figure 1) is a winter-annual grass that reproduces only from seed and germinates in fall when temperatures are moderate to high (64 to 82ºF). The plant has slim, erect shoots that grow about 4 to 18 inches tall with tiny hairs that make it appear smooth.

Seedling leaves appear very narrow because they are rolled or folded lengthwise. Each plant produces about 35 to 50 seeds. Ventenata is readily identified in May through June by the presence of reddish-black nodes on culms.

Plants take on a shiny appearance in June through July, and then the open panicle emerges. As the plants senesce in late July into August, the awns become bent and twisted.

Ventenata was first reported in the state of Washington in 1952. It currently is found in Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Utah, Montana, Wyoming, Wisconsin, New York and Maine, growing from near sea level to 6000 feet within moderate precipitation zones of 14 to 44 inches per year.

Ventenata typically occupies south-facing hillsides with shallow, rocky, clay or clay-loam soils and in sites that are flooded in early spring but dry out by late spring. Ventenata is invading roadsides, hay, pastures, rangeland and CRP in the western U.S., where it is replacing perennial grass species.

Ventenata has little to no forage value for livestock or wildlife and has a shallow root system that may not hold soils in place as well as native or other grass species, thus leading to erosion of occupied sites.

Management of ventenata is similar to other annual grasses, and the key to success is to keep it from setting seed, as that is its only means of reproduction.

The best way to prevent ventenata from invading a new site is to maintain a vigorous stand of perennial vegetation. Mowing during heading is nearly impossible, as the plant simply bends over or becomes tangled in the mower.

Mowing frequently during the growing season has shown to be successful if plants can be kept at a minimal height until soil moisture is exhausted.

Fire does not control ventenata. Glyphosate, imazapic, rimsulfuron, sulfometuron and sulfosulfuron all effectively decrease ventenata populations, and all herbicides should be applied pre-emergence or early post-emergence.

Often, seeding infested areas after weed populations are successfully decreased is a necessary step in effective, long-lasting invasive weed management.

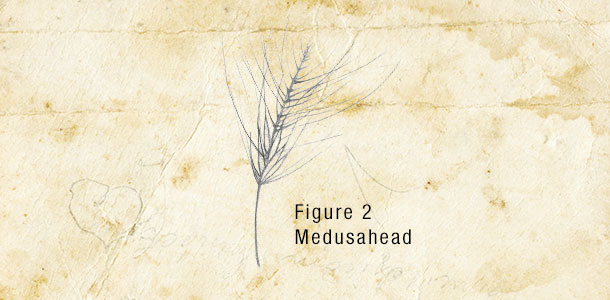

Medusahead

(Taeniatherum caput-medusae)

Medusahead (Figure 2) is a winter-annual grass that reproduces solely from seed. Medusahead invades and dominates rangeland that has been degraded by overgrazing, cultivation or frequent fires.

Medusahead grows about 6 to 20 inches tall to a maximum of 24 inches with one or more shoots developing from its base. Its seedhead is a spike-type and occurs toward the tops of culms and is similar in appearance to bottlebrush squirreltail (Elymus elymoides).

Each node will produce two to three spikelets; each spikelet contains one seed, and 20 or more seeds are produced per seedhead.

Medusahead seedheads have two types of awns; short awns grow 0.8 to 1.6 inches long and protrude at wide angles from the spike; long awns are more upright and grow 1.6 to 3 inches long.

The rough, long awns adhere to animal coats and aid seed dispersal. Germination may occur in fall, winter or spring, but fall germination is most prevalent and medusahead plants may product up to 6,000 seeds per square foot. Seeds under litter and in soil survive for at least a year and growth may continue over winters in mesic, moderate climates.

Regardless of when germination occurs, plants produce seed by early summer. Medusahead seeds mature usually by late June into July.

Medusahead is native to the Mediterranean region of Europe and was introduced into the U.S. in the 1880s. It did not spread rapidly until the 1950s, and its current U.S. distribution includes Washington, Montana, Oregon, California, Nevada, Utah, Idaho, Pennsylvania, New York and Connecticut.

Medusahead grows in areas where winters are mild to cold but are hot during the summer. Medusahead occupies these temperate zones where precipitation ranges from 10 to 40 inches annually with an upper limit of 50 inches.

Medusahead often dominates plant communities that have been disturbed where soils have a high moisture-holding capacity and infiltration is slow.

Arid sites that are very vulnerable to invasion by medusahead have high clay content found at or near the soil surface. In areas with well-balanced moisture supply, soils that are moderately well-developed are as susceptible to invasion as those with well-developed soils.

Medusahead and cheatgrass often compete, but soil and topographic characteristics influence their distribution. Medusahead is considered largely unpalatable for most livestock species for the entire growing season because plants contain high amounts of silica.

Where medusahead has replaced cheatgrass on western U.S. rangeland, carrying capacity is often decreased 50 to 75 percent.

Medusahead also is unimportant as wildlife forage. In general, medusahead is less palatable to ungulates than cheatgrass and decreases wildlife carrying capacity.

Additionally, seeds of medusahead are indigestible to wild birds, and mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) use medusahead very little while cheatgrass is readily grazed by mule deer.

Medusahead is fire-adapted and readily establishes after fire from the soil seed reserve present in the burned area and from seed dispersed from other areas after fire.

The rapid expansion of medusahead in the western U.S. is a significant management concern. The U.S. Department of Interior Bureau of Land Management found on lands it manages in the West that more than 3.3 million acres are considered cheatgrass or medusahead monocultures, nearly 14 million acres are infested with one or both of these annual grasses, and more than 62 million acres are at risk of invasion by cheatgrass and medusahead if disturbance occurs. The best defense against medusahead invasion is a vigorous stand of perennial vegetation.

Medusahead populations can be decreased by mechanical means, burning or herbicide applications, and these often must be combined with seeding of desirable plants to keep managed sites from being re-invaded by medusahead or other annual grasses. While tillage will control medusahead, such practices are rarely recommended on rangeland where medusahead typically is problematic.

Burning can be effective at lower-elevation, warm-winter sites such as in California’s Central Valley and foothills, but burning at high-elevation, cool sites usually fails to control medusahead.

Glyphosate, imazapic, rimsulfuron, sulfometuron and sulfometuron plus chlorsulfuron all control medusahead and are commonly recommended. Glyphosate should be applied in late winter into early spring after all seedlings have germinated but before seedhead formation and all other herbicides should be applied pre-emergence or early post-emergence before medusahead tillers.

Re-vegetation of infested sites where medusahead populations have been successfully decreased with adapted native species may prevent it from re-invading.

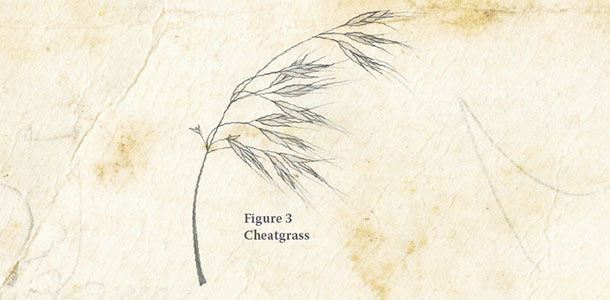

Cheatgrass: An old foe

Cheatgrass (Figure 3) infests a greater area in the western U.S. than does medusahead and tolerates drier climates. Cheatgrass will grow in most soils; it is most competitive and dominant on deep, loamy or coarse soils but does not fare well on fine-textured soils.

Cheatgrass is consumed by all of the herbivores in its native range and evolved with grazing, but its period of palatability is usually only about six weeks.

The greater sage grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus) is being considered for listing as endangered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service due to habitat loss.

Researchers reported that sage grouse habitat can be improved by lowering big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata) cover with low rates of tebuthiuron, which increases grass and forb production and improves nesting and foraging opportunities, which could aid bird populations.

Cheatgrass-fueled fires also have been identified as a major factor decreasing sage grouse habitat. Ants are a significant part of young sage grouse diets, but ant abundance following fire is decreased, thereby impacting brood survival.

Big sagebrush cover also is decreased after wildfire by 95 percent, which then decreases escape and nesting cover for sage grouse.

The tragedy associated with sage grouse decline is that much of its historic range is managed by the Bureau of Land Management, and cheatgrass has invaded sage grouse range including on lands managed by the BLM. We possess the knowledge to adequately decrease cheatgrass abundance and recover those sites with seeding.

Private and public land managers can recover habitat lost to cheatgrass, and they need to cooperate and collaborate to develop and implement plans that will successfully recover habitat and promote bird population recovery.

Doing so would prevent an endangered listing of the sage grouse and avoid the oppressive land-use measures that would follow.