Know the objective behind the index

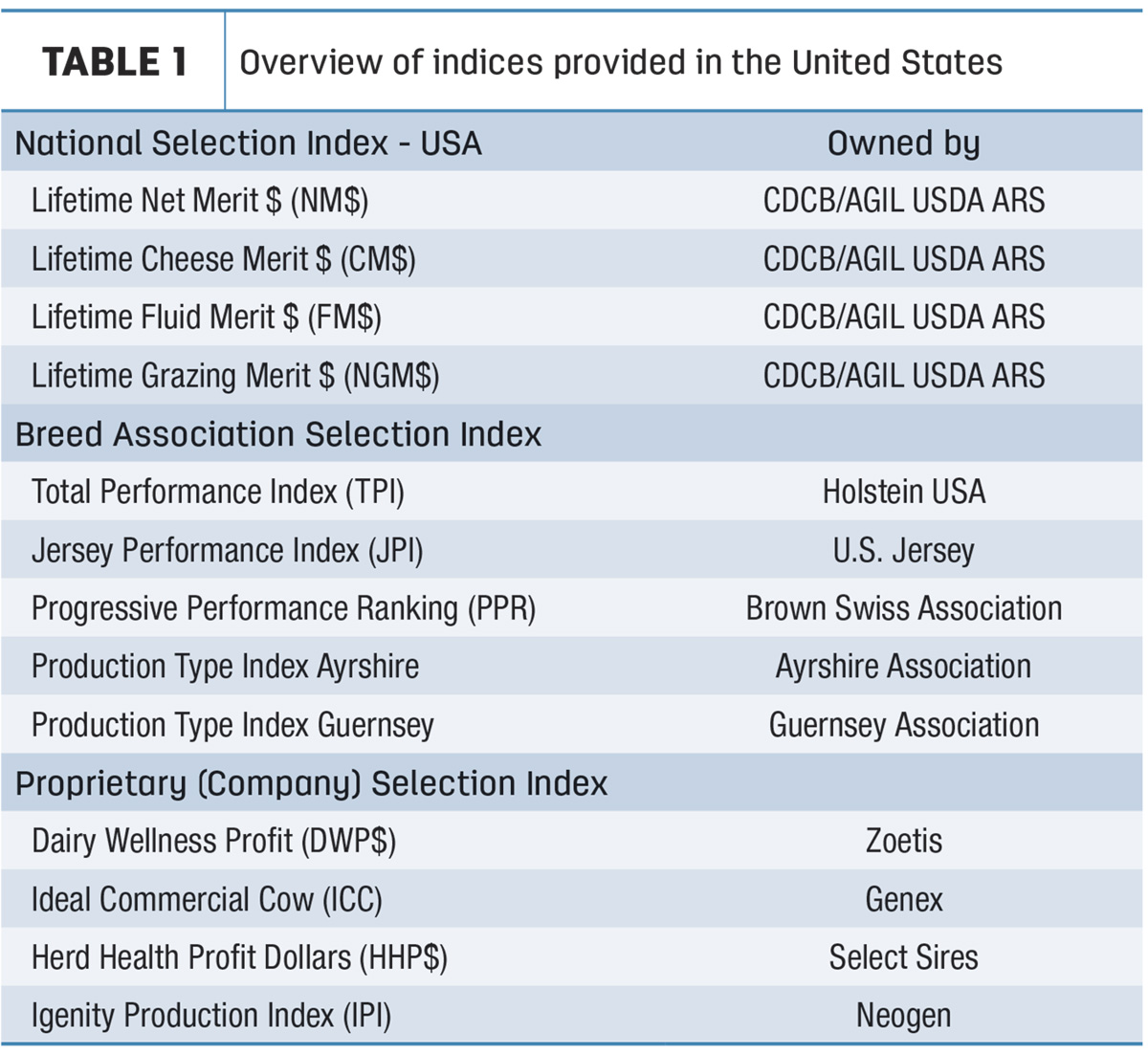

Who owns and creates the index and why did they choose to do so? Tables 1 and 2 outline most indexes available in the U.S.

The main indexes in the U.S. correlate very highly. Their equations are public, and many of the same traits are in each index. In fact, when a new national trait is launched, often Net Merit (NM$) and TPI are updated simultaneously. And yet, they have a different selection goal. It is important to realize that NM$ and TPI are distinctly different indexes by what they aim to achieve and who decides that aim.

TPI is owned and managed by Holstein Association USA, just like JPI (Jersey), Production Type Index (PTI) (Ayrshire and Guernsey) and Progressive Performance Ranking (PPR) (Brown Swiss) are owned by their respective breed associations as well. Therefore, TPI selects for the best Holstein animal where "best" is defined by qualitative analyses that are driven by empirical and subjective factors determined by experts working for or with Holstein Association USA. The traits and weights in TPI are opinion based. They are backed up by science and mathematics but are subjective when it comes to how the association agrees they measure up to the desired Holstein cow of the future.

NM$ is the U.S. national index and was created by the USDA to give U.S. producers a single economic dollar value for lifetime profitability of the U.S. commercial dairy cow. Thereby, NM$ includes all developed national traits with economic value to lifetime profitability. While there are discussions in many committees about the traits and weights in NM$, a newly developed trait gets added to NM$ by default if it has economic value and correlation to lifetime profitability. The weights are calculated by genetic parameters and current economic weights.

Lastly, there are the proprietary indexes owned by private companies. The Dairy Wellness Profit Index (DWP$) is a good example of a well-known proprietary index owned by Zoetis. Being owned by a business, the objective of a proprietary index is always to create additional revenue (through sales of genomic tests or genetics). The selection goals are often fulfilling a gap of a producer need that existing indexes do not cover. This can be a different weighing of traits or the development of novel traits that are presented in an index for simplicity. In Zoetis’s example, DWP$ offered a larger emphasis on health and access to proprietary health traits on cows and calves that weren’t present (yet) through the national evaluation.

Some proprietary indexes do not advertise a clear selection goal and simply state the response to selection that can be expected, such as better efficiency, better health or increased immunity. That is fine if the producer is informed about what the content of the index is. It is important that you make sure that the index covers selection on the whole animal to avoid achieving adverse response to selection in traits that are not considered.

Know what is in the index

The content of the national indexes, as well as most of the breed association indexes, are publicly available on the websites of the Council of Dairy Cattle Breeding and respective breed associations. The indexes are updated regularly with new economic values and traits. These changes are publicly announced and explained.

Unfortunately, it is a lot more difficult to know the contents of the proprietary indexes because that information is often kept confidential. From a business perspective, that makes sense. Why make your secret recipe public for the competitor to repeat? But for a producer, it’s hard to know if the index fits your breeding goal if you don’t know what the index selects for. Even if you trust the company representative for knowing your needs, you still need to consider the traits that are not in the index and avoid double counting the ones that are. Make sure you get to know how the index is constructed before starting selection.

Is the index available on bulls across the board?

The whole point of a selection index is to summarize traits into a single value that can be used for comparison of animals. Breed association indexes are calculated on registered animals that can be compared, and national indexes are compared on all animals receiving a U.S. genetic evaluation.

Proprietary indexes are not always calculated for all bulls and cows, which is a concern. Especially when proprietary traits are involved, companies like to keep predictions of those traits and indexes exclusive to their own animals or to animals that are tested by their products. That makes comparison across the board very difficult, if not impossible.

If you do not want to work exclusively with a particular portfolio of bulls, it becomes difficult to select for a proprietary index in such a way that you achieve the selection objective that is set out by that index. In essence, you are forced to use multiple indexes on a variety of bulls, which blurs your breeding goal. So, if the proprietary index fits your breeding goal, you may have to concede to using just the bulls that have that value. If you do not want to be that restricted, it may be best to choose a non-proprietary index. Do not start mixing and matching indexes based on what bulls you like because you will slow down genetic progress by not having a clear direction.

Consider creating your own index

In a perfect world, every producer should have his or her own selection index. Many large breeders already do. Selection objectives and indexes should vary as widely as the variety of dairy producers. So, creating a herd’s own index is recommended, but complicated. There are tools available to create selection indexes, but they may offer black boxes that do not explain what is being calculated.

When creating an index, it is recommended to consult with a geneticist or adviser who can help to make sure the index is constructed in a way that accounts for accurate genetic and phenotypic relationships between the selection traits. This may sound easy when thinking of the negative relationship between production and daughter pregnancy rate. But considering the genetic correlation of daughter pregnancy rate with productive life – a trait calculated using several indicator traits itself – demonstrates how complicated it can get. Substantial losses can occur when selection is intense and indirect values are ignored.

Conclusion

Genetic improvement is realized when there is continuous long-term selection for a constant breeding goal. Choosing a selection index is therefore a commitment. Changing or mixing selection indexes restricts genetic improvement by change of direction. The defining of a clear breeding goal is key. This should be independent from ranking lists and marketing, which can distract. It is then important to find out the objective and content of the index. Ask questions when that information is not publicly available.